The Malleus Maleficarum, usually translated as the Hammer of Witches, is the best known treatise purporting to be about witchcraft. It was written by the German Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer and first published in the German city of Speyer in 1486. Some describe it as the compendium of literature in demonology of the 15th century. Kramer blamed women for his own lust, and presented his views as the Church's position. The book was condemned by top theologians of the Inquisition at the Faculty of Cologne for recommending unethical and illegal procedures, and for being inconsistent with Catholic doctrines of demonology.

Witchcraft, as most commonly understood in both historical and present-day communities, is the use of alleged supernatural powers of magic. A witch is a practitioner of witchcraft. Traditionally, "witchcraft" means the use of magic or supernatural powers to inflict harm or misfortune on others, and this remains the most common and widespread meaning. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, "Witchcraft thus defined exists more in the imagination of contemporaries than in any objective reality. Yet this stereotype has a long history and has constituted for many cultures a viable explanation of evil in the world". The belief in witchcraft has been found in a great number of societies worldwide. Anthropologists have applied the English term "witchcraft" to similar beliefs in occult practices in many different cultures, and societies that have adopted the English language have often internalised the term.

A witch-hunt, or a witch purge, is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. Practicing evil spells or incantations was proscribed and punishable in early human civilizations in the Middle East. In medieval Europe, witch-hunts often arose in connection to charges of heresy from Christianity. An intensive period of witch-hunts occurring in Early Modern Europe and to a smaller extent Colonial America, took place about 1450 to 1750, spanning the upheavals of the Counter Reformation and the Thirty Years' War, resulting in an estimated 35,000 to 50,000 executions. The last executions of people convicted as witches in Europe took place in the 18th century. In other regions, like Africa and Asia, contemporary witch-hunts have been reported from sub-Saharan Africa and Papua New Guinea, and official legislation against witchcraft is still found in Saudi Arabia and Cameroon today.

Heinrich Kramer, also known under the Latinized name Henricus Institor, was a German churchman and inquisitor. With his widely distributed book Malleus Maleficarum (1487), which describes witchcraft and endorses detailed processes for the extermination of witches, he was instrumental in establishing the period of witch trials in the early modern period.

Matthew Hopkins was an English witch-hunter whose career flourished during the English Civil War. He was mainly active in East Anglia and claimed to hold the office of Witchfinder General, although that title was never bestowed by Parliament.

The Vardø witch trials, which took place in Vardø in Finnmark in Northern Norway in 1621, was the first major witch trial of Northern Norway and one of the biggest witch trials in Scandinavia. It was the first of the three big mass trials of Northern Norway, followed by the Vardø witch trials (1651–1653) and the Vardø witch trials (1662-1663), and one of the biggest witch trials in Norway.

The witch trials of Vardø were held in Vardø in Finnmark in Northern Norway in the winter of 1662–1663 and were one of the biggest in Scandinavia. Thirty women were put on trial, accused of sorcery and making pacts with the Devil. One was sentenced to a work house, two tortured to death, and eighteen were burned alive at the stake.

The trials of the Pendle witches in 1612 are among the most famous witch trials in English history, and some of the best recorded of the 17th century. The twelve accused lived in the area surrounding Pendle Hill in Lancashire, and were charged with the murders of ten people by the use of witchcraft. All but two were tried at Lancaster Assizes on 18–19 August 1612, along with the Samlesbury witches and others, in a series of trials that have become known as the Lancashire witch trials. One was tried at York Assizes on 27 July 1612, and another died in prison. Of the eleven who went to trial – nine women and two men – ten were found guilty and executed by hanging; one was found not guilty.

The witch-cult hypothesis is a discredited theory that the witch trials of the Early Modern period were an attempt to suppress a pagan religion that had survived the Christianization of Europe. According to its proponents, accused witches were actually followers of this alleged religion. They argue that the supposed 'witch cult' revolved around worshiping a Horned God of fertility and the underworld, whose Christian persecutors identified with the Devil, and whose followers held nocturnal rites at the witches' Sabbath.

The Samlesbury witches were three women from the Lancashire village of Samlesbury – Jane Southworth, Jennet Bierley, and Ellen Bierley – accused by a 14-year-old girl, Grace Sowerbutts, of practising witchcraft. Their trial at Lancaster Assizes in England on 19 August 1612 was one in a series of witch trials held there over two days, among the most infamous in English history. The trials were unusual for England at that time in two respects: Thomas Potts, the clerk to the court, published the proceedings in his The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster; and the number of the accused found guilty and hanged was unusually high, ten at Lancaster and another at York. All three of the Samlesbury women were acquitted.

Sidonia von Borcke (1548–1620) was a Pomeranian noblewoman who was tried and executed for witchcraft in the city of Stettin. In posthumous legends, she is depicted as a femme fatale, and she has entered English literature as Sidonia the Sorceress. She had lived in various towns and villages throughout the country.

The Great Scottish Witch Hunt of 1597 was a series of nationwide witch trials that took place in the whole of Scotland from March to October 1597. At least 400 people were put on trial for witchcraft and various forms of diabolism during the witch hunt. The exact number of those executed is unknown, but is believed to be about 200. The Great Scottish Witch Hunt of 1597 was the second of five nationwide witch hunts in Scottish history, the others being The Great Scottish Witch Hunt of 1590–91, The Great Scottish Witch Hunt of 1628–1631, The Great Scottish witch hunt of 1649–50 and The Great Scottish Witch Hunt of 1661–62.

Grace White Sherwood (1660–1740), called the Witch of Pungo, is the last person known to have been convicted of witchcraft in Virginia.

The Pittenweem witches were five Scottish women accused of witchcraft in the small fishing village of Pittenweem in Fife on the east coast of Scotland in 1704. Another two women and a man were named as accomplices. Accusations made by a teenage boy, Patrick Morton, against a local woman, Beatrix Layng, led to the death in prison of Thomas Brown, and, in January 1705, the murder of Janet Cornfoot by a lynch mob in the village.

The witch trials in Connecticut, also sometimes referred to as the Hartford witch trials, occurred from 1647 to 1663. They were the first large-scale witch trials in the American colonies, predating the Salem Witch Trials by nearly thirty years. John M. Taylor lists a total of 37 cases, 11 of which resulted in executions. The execution of Alse Young of Windsor in the spring of 1647 was the beginning of the witch panic in the area, which would not come to an end until 1670 with the release of Katherine Harrison.

Mary Pannal was an English herbalist and cunning woman who was accused of, and executed for, witchcraft in 1603.

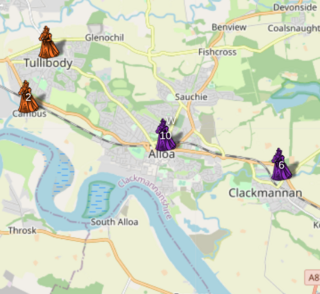

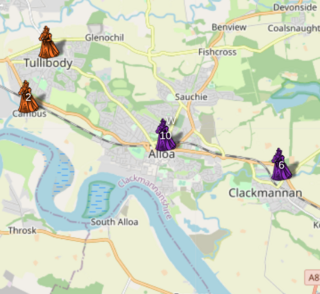

Margaret Duchill was a Scottish woman who confessed to witchcraft at Alloa during the year 1658. She was implicated by others and she named other women. She was executed on 1 June 1658.

The Maryland Witch Trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in Colonial Maryland between June 1654, and October 1712. It was not unique, but is a Colonial American example of the much broader phenomenon of witch trials in the early modern period, which took place also in Europe.

Marioun Twedy or Marion Tweedy was accused of witchcraft in Peebles in the Scottish Borders in 1649. She was accused of causing the death of a woman and her child and of using charms to cure animals. She refused to confess to these accusations. However, the witchpricker condemned her for finding 'the devil's mark' on her.