Related Research Articles

Macedonian is an Eastern South Slavic language. It is part of the Indo-European language family, and is one of the Slavic languages, which are part of a larger Balto-Slavic branch. Spoken as a first language by around two million people, it serves as the official language of North Macedonia. Most speakers can be found in the country and its diaspora, with a smaller number of speakers throughout the transnational region of Macedonia. Macedonian is also a recognized minority language in parts of Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Romania, and Serbia and it is spoken by emigrant communities predominantly in Australia, Canada and the United States.

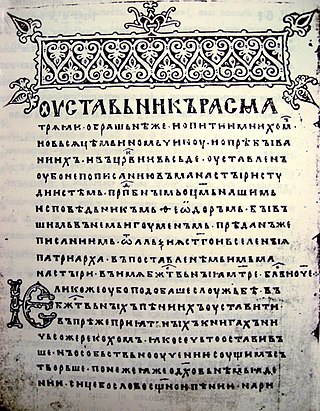

Old Church Slavonic or Old Slavonic is the first Slavic literary language.

Slavic or Slavonicstudies, also known as Slavistics, is the academic field of area studies concerned with Slavic areas, languages, literature, history, and culture. Originally, a Slavist or Slavicist was primarily a linguist or philologist researching Slavistics. Increasingly, historians, social scientists, and other humanists who study Slavic area cultures and societies have been included in this rubric.

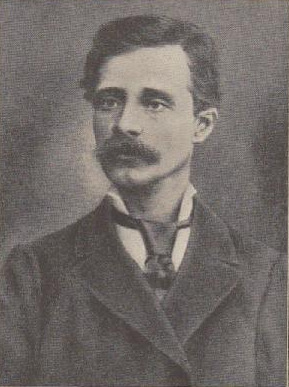

Georgi Nikolov Delchev, known as Gotse Delchev or Goce Delčev, was an important Macedonian Bulgarian revolutionary (komitadji), active in the Ottoman-ruled Macedonia and Adrianople regions at the turn of the 20th century. He was the most prominent leader of what is known today as the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO), a secret revolutionary society that was active in Ottoman territories in the Balkans at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. Delchev was its representative in Sofia, the capital of the Principality of Bulgaria. As such, he was also a member of the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee (SMAC), participating in the work of its governing body. He was killed in a skirmish with an Ottoman unit on the eve of the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie uprising.

Grigor Stavrev Parlichev was a Bulgarian writer, teacher and translator. He was born on January 18, 1830, in Ohrid, Ottoman Empire and died in the same town on January 25, 1893. Although he thought of himself as a Bulgarian, according to the Macedonian historiography he was an ethnic Macedonian.

The Bulgarian Orthodox Church, legally the Patriarchate of Bulgaria, is an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox jurisdiction based in Bulgaria. It is the oldest Slavic Orthodox church, with some 6 million members in Bulgaria and between 1.5 and 2 million members in a number of other European countries, Asia, the Americas, Australia, and New Zealand. It was recognized as autocephalous in 1945 by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople.

The Eyalet of Silistra or Silistria, later known as Özü Eyalet meaning Province of Ochakiv was an eyalet of the Ottoman Empire along the Black Sea littoral and south bank of the Danube River in southeastern Europe. The fortress of Akkerman was under the eyalet's jurisdiction. Its reported area in the 19th century was 71,140 square kilometres (27,469 sq mi).

Torlakian, or Torlak, is a group of Eastern South Slavic dialects of southeastern Serbia, Kosovo, northeastern North Macedonia, and northwestern Bulgaria. Torlakian, together with Bulgarian and Macedonian, falls into the Balkan Slavic linguistic area, which is part of the broader Balkan sprachbund. According to UNESCO's list of endangered languages, Torlakian is vulnerable.

The history of the Macedonian language refers to the developmental periods of current-day Macedonian, an Eastern South Slavic language spoken on the territory of North Macedonia. The Macedonian language developed during the Middle Ages from the Old Church Slavonic, the common language spoken by Slavic people.

The name Macedonia is used in a number of competing or overlapping meanings to describe geographical, political and historical areas, languages and peoples in a part of south-eastern Europe. It has been a major source of political controversy since the early 20th century. The situation is complicated because different ethnic groups use different terminology for the same entity, or the same terminology for different entities, with different political connotations.

The Codex Marianus is an Old Church Slavonic fourfold Gospel Book written in Glagolitic script, dated to the beginning of the 11th century, which is, one of the oldest manuscript witnesses to the Old Church Slavonic language, one of the two fourfold gospels being part of the Old Church Slavonic canon.

Macedonian literature begins with the Ohrid Literary School in the First Bulgarian Empire in 886. These first written works in the dialects of the Old Church Slavonic were religious. The school was established by St. Clement of Ohrid. The Macedonian recension at that time was part of the Old Church Slavonic and it did not represent one regional dialect but a generalized form of early Eastern South Slavic. The standardization of Macedonian in the 20th century provided good ground for further development of the modern Macedonian literature and this period is the richest one in the history of the literature itself.

Theodosius of Sinai, was a Bulgarian priest, writer and printer. He founded the first Bulgarian printing-house in Thessaloniki. Although Theodosius died before the earliest expressions of incipient Macedonian national identity, he is considered an ethnic Macedonian in North Macedonia.

Yunus Pasha was an Ottoman statesman. He was Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire for eight months in 1517, serving from January 30 until his death on September 13.

Saint Clement or Kliment of Ohrid was one of the first medieval Bulgarian saints, scholar, writer, and apostle to the Slavs. He was one of the most prominent disciples of Cyril and Methodius and is often associated with the creation of the Glagolitic and Cyrillic scripts, especially their popularisation among Christianised Slavs. He was the founder of the Ohrid Literary School and is regarded as a patron of education and language by some Slavic people. He is considered to be the first bishop of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, one of the Seven Apostles of Bulgarian Orthodox Church since the 10th century, and one of the premier saints of modern Bulgaria. The mission of Clement was the crucial factor which transformed the Slavs in then Kutmichevitsa into Bulgarians. Clement is also the patron saint of North Macedonia, the city of Ohrid and the Macedonian Orthodox Church.

Pyotr Danilovich Draganov was a Russian philologist and slavist.

Voynuks were members of the privileged Ottoman military social class established in the 1370s or the 1380s. Voynuks were tax-exempt non-Muslim, usually Slavic, and also non-Slavic Vlach Ottoman subjects from the Balkans, particularly from the regions of southern Serbia, Macedonia, Thessaly, Bulgaria and Albania and much less in Bosnia and around the Danube–Sava region. Voynuks belonged to the Sanjak of Voynuk which was not a territorial unit like other sanjaks but a separate organisational unit of the Ottoman Empire.

Dositije Novaković was a Serbian Orthodox monk and revolutionary who participated in the First Serbian Uprising.

Todor Vojinović (1760–1813) was a Serbian voivode and a revolutionary during the First Serbian Uprising. He was killed while fighting the Ottoman Turks in Serbia in 1813.

Ivan Dorovský was a Czech Balkanologist of Macedonian origin. He worked as a literary scholar, translator, poet and publicist, university professor at Masaryk University, and Slavist. He was also the Chairman of the Society of Friends of the South Slavs. He was the 2008 recipient of the Macedonian honorary Racin Recognition for his contribution and affirmation of Macedonian literature and culture, and the 2013 recipient of the F. A. Zach Prize for his contribution to the relationship with the Serbian nation.

References

- 1 2 Antoanetta Granberg, "Transferred in Translation. Making a State in Early Medieval Bulgarian Genealogies" (PDF). (252 KB), SLAVICA HELSINGIENSIA 35, 2008

- ↑ Yassen Borislavov (1 January 2004). Bulgarian wine book: history, culture, cellars, wines. TRUD Publishers. p. 74. ISBN 978-954-528-478-6 . Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ↑ Anonymous classics: a list of uniform headings for European literatures. Second edition revised by the Working group set up by the IFLA Standing Committee of the Section on Cataloguing

- 1 2 Khristo Angelov Khristov; Dimitǔr Konstantinov Kosev (1963). A short history of Bulgaria. Foreign Languages Press. p. 128. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ↑ United Center for Research and Training in History; Edinen t︠s︡entŭr za nauka i podgotovka na kadri po istorii︠a︡ (1987). Revue bulgare d'histoire. Pub. House of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. p. 93. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ↑ Research Programme for Macedonian Studies (New Delhi, India) (1991). Macedonian studies. Research Programme for Macedonian Studies. p. 60. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ↑ Vernon J. Parry; Malcolm Yapp (1975). War, technology and society in the Middle East. Oxford University Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-19-713581-5 . Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- 1 2 Colin Imber (1990). The Ottoman Empire, 1300-1481. Isis Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-975-428-015-9 . Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ↑ Nejat Göyünç; Klaus Kreiser; Christoph K. Neumann (1997). Das osmanische Reich in seinen Archivalien und Chroniken: Nejat Göyünç zu Ehren. In Kommission bei Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart. p. 32. ISBN 978-3-515-07034-8 . Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ↑ University of Melbourne. Dept. of Russian and Language Studies; Australian and New Zealand Slavists' Association; Australasian Association for Study of the Socialist Countries (1 January 2003). Australian Slavonic and East European studies: journal of the Australian and New Zealand Slavists' Association and of the Australasian Association for Study of the Socialist Countries. Dept. of Russian and Language Studies, University of Melbourne. p. 7. Retrieved 10 November 2011.