Related Research Articles

Angelina Emily Grimké Weld was an American abolitionist, political activist, women's rights advocate, and supporter of the women's suffrage movement. She and her sister Sarah Moore Grimké were considered the only notable examples of white Southern women abolitionists. The sisters lived together as adults, while Angelina was the wife of abolitionist leader Theodore Dwight Weld.

Lydia Maria Child was an American abolitionist, women's rights activist, Native American rights activist, novelist, journalist, and opponent of American expansionism.

Maria Weston Chapman was an American abolitionist. She was elected to the executive committee of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1839 and from 1839 until 1842, she served as editor of the anti-slavery journal The Non-Resistant.

Aunt Phillis's Cabin; or, Southern Life as It Is by Mary Henderson Eastman is a plantation fiction novel, and is perhaps the most read anti-Tom novel in American literature. It was published by Lippincott, Grambo & Co. of Philadelphia in 1852 as a response to Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, published earlier that year. The novel sold 20,000–30,000 copies, far fewer than Stowe's novel, but still a strong commercial success and bestseller. Based on her growing up in Warrenton, Virginia, of an elite planter family, Eastman portrays plantation owners and slaves as mutually respectful, kind, and happy beings.

The first Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women was held in New York City on May 9–12, 1837 to discuss the American abolition movement. This gathering represented the first time that women from such a broad geographic area met with the common purpose of promoting the anti-slavery cause among women, and it also was likely the first major convention where women discussed women's rights. Some prominent women went on to be vocal members of the Women's Suffrage Movement, including Lucretia Mott, the Grimké sisters, and Lydia Maria Child. After the first convention in 1837, there were also conventions in 1838 and 1839

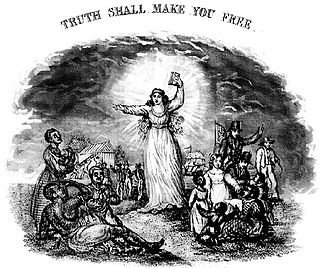

The Liberty Bell, by Friends of Freedom, was an annual abolitionist gift book, edited and published by Maria Weston Chapman, to be sold or gifted to participants in the National Anti-Slavery Bazaar organized by the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society. Named after the symbol of the American Revolution, it was published nearly every year from 1839 to 1858.

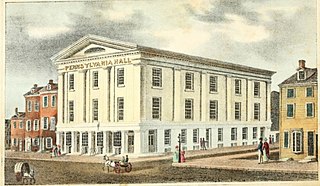

Pennsylvania Hall, "one of the most commodious and splendid buildings in the city," was an abolitionist venue in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, built in 1837–38. It was a "Temple of Free Discussion", where antislavery, women's rights, and other reform lecturers could be heard. Four days after it opened it was destroyed by arson, the work of an anti-abolitionist mob. Except for the burning of the White House and the Capitol during the War of 1812, it was the worst case of arson in American history up to that date.

Mary Grew was an American abolitionist and suffragist whose career spanned nearly the entire 19th century. She was a leader of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society and the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. She was one of eight women delegates who were denied their seats at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in 1840. An editor and journalist, she wrote for abolitionist newspapers and chronicled the work of Philadelphia's abolitionists over more than three decades. She was a gifted public orator at a time when it was still noteworthy for women to speak in public. Her obituary summarized her impact: "Her biography would be a history of all reforms in Pennsylvania for fifty years."

The free-produce movement was an international boycott of goods produced by slave labor. It was used by the abolitionist movement as a non-violent way for individuals, including the disenfranchised, to fight slavery.

Lucretia Mott was an American Quaker, abolitionist, women's rights activist, and social reformer. She had formed the idea of reforming the position of women in society when she was amongst the women excluded from the World Anti-Slavery Convention held in London in 1840. In 1848, she was invited by Jane Hunt to a meeting that led to the first public gathering about women's rights, the Seneca Falls Convention, during which the Declaration of Sentiments was written.

The Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society (1833–1840) was an abolitionist, interracial organization in Boston, Massachusetts, in the mid-19th century. "During its brief history ... it orchestrated three national women's conventions, organized a multistate petition campaign, sued southerners who brought slaves into Boston, and sponsored elaborate, profitable fundraisers."

The Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (PFASS) was founded in December 1833 and dissolved in March 1870 following the ratification of the 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. It was founded by eighteen women, including Mary Ann M'Clintock, Margaretta Forten, her mother Charlotte, and Forten's sisters Sarah and Harriet.

In the United States, abolitionism, the movement that sought to end slavery in the country, was active from the late colonial era until the American Civil War, the end of which brought about the abolition of American slavery through the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Julia Williams was an American abolitionist who was active in Massachusetts. Born free in Charleston, South Carolina, she moved with her family as a child to Boston, Massachusetts, and was educated in the North. A member of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, she attended the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women in New York in 1837. She married abolitionist Henry Highland Garnet and in 1852 they traveled to Jamaica to work as missionaries, where she headed an industrial school for girls. After the American Civil War, she worked with freedmen in Washington, DC to establish their new lives.

Sarah Hussey Earle was an abolitionist, American Quaker, and women's rights activist. She was born in Nantucket, Massachusetts and married John Milton Earle on June 6, 1821, before moving to Worcester, Massachusetts. She founded the Worcester Ladies Anti-Slavery Sewing Circle and served as its president in 1839. She assisted and served on committees of the Worcester County Anti-Slavery Society, South Division from 1841 and was the first woman to serve as one of the vice presidents of the South Division before her death in 1858. Additionally, Earle coordinated Worcester anti-slavery fairs from 1848 and organized fundraising for the American Anti-Slavery Society, eventually sending donations to Maria Weston Chapman. She founded and was president of the Worcester City Anti-Slavery Society, in addition to organizing lectures for the organization. She gave the opening address to the first National Women's Rights Convention, which was held in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1850, and was elected president of the 1854 New England Women's Rights Convention in Boston.

The Fall River Female Anti-Slavery Society was an abolitionist group in Fall River, Massachusetts, formed in 1835. It was the second female anti-slavery society in the city. One of its founding members was Elizabeth Buffum Chace (1806-1899).

Anne Warren Weston was an American abolitionist. She is largely memorialized by the letters she wrote to the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, and others.

Thankful Southwick was an affluent Quaker abolitionist and women's rights activist in Boston, Massachusetts. Thankful was lifelong abolitionist who joined the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society in 1835 with her three daughters. She was present at both the 1835 Boston Mob and the Abolition Riot of 1836. During the 1840 schism in the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, Thankful sided with the Westons, Chapmans, Childs, Sergeants, and other radical Garrisonians to reestablish the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society. She also later joined the New England Non Resistance Society. She held several elected offices within the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, including counselor in 1837, as well as President in 1840, 1841, 1842, and 1844. Thankful was also involved in the women's rights movement and was an attendee and signer of the call of the first National Women's Rights Convention held in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1850. Thankful and Joseph Southwick's house was both a gathering place for fellow abolitionists and a stop on the Underground Railroad for fugitive slaves. During her years of activism in Boston, Thankful and her family were closely acquainted with notable abolitionists and women 's rights activists, including William Lloyd Garrison, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Frederick Douglass, Lydia Maria Child, Maria Weston Chapman, and George Thompson.

The Ladies' New York City Anti-Slavery Society was a group of white Christian women in New York City who created an abolitionist society based on their religious views. At this time moral reforms were becoming popular and were encouraged by preachers. This group was founded in 1835 and had about 200 members. They felt as though they could help end slavery by using religion to pray and spread anti-slavery ideas, but this limited their activities, because they believed in the idea of separate spheres they did not participate in anything that was in the public sphere alongside men. Their society wrote letters, circulated petitions and held parlor lectures and conventions. There was a lot of controversy around this group within the women's anti-slavery movement because they did not allow black members. They also often fought against the women's rights movement. These views on women's rights eventually led to the end of the society because it was agreed that women should not be allowed to participate in organizations and voice their opinions alongside men. This led the New York City Anti-Slavery Society, which was male only, and the Ladies New York City Anti-Slavery Society to walk out of a planned debate that was held by the American Anti-Slavery Society. After this, the women's society supposedly served as an auxiliary of a new society the men created called the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. They did not have any recorded activity after this debate.

Abolitionist children’s literature includes works written for children by authors committed to the movement to end slavery. It aimed to instill in young readers an understanding of slavery, racial hierarchies, sympathy for the enslaved, and a desire for emancipation. A variety of literary forms were used by abolitionist children’s authors including, short stories, poems, songs, nursery rhymes and dialogues, much of it written by white women. Pamphlets, picture books and periodicals were the primary forms of abolitionist children’s literature, often using Biblical themes to reinforce the wickedness of slavery. Abolitionist children's literature was countered with pro-slavery material aimed at children, which attempting to depict slavery as a noble pursuit, and slaves as stupid and grateful, or evil.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Van Broekhoven, Deborah (1998). "'Better than a clay club': The organization of anti‐slavery fairs, 1835–60". Slavery & Abolition. 19 (1): 24–45. doi:10.1080/01440399808575227. ISSN 0144-039X.

- ↑ Winch, Julie (2000). Douglass, Sarah Mapps (1806-1882), abolitionist and educator. American National Biography Online. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ "Bazaars and Fair Ladies: the History of the American Fundraising Fair". The Annals of Iowa. 59 (3): 299–300. 2000. doi: 10.17077/0003-4827.10374 . ISSN 0003-4827.

- ↑ Venet, Wendy Hamand; Taylor, Clare (1996). "Women of the Anti-Slavery Movement: The Weston Sisters". The Journal of American History. 83 (1): 209. doi:10.2307/2945530. ISSN 0021-8723.

- ↑ Brandon-Falcone, Janice (December 1994). "Review of Debra Gold Hansen, Strained Sisterhood: Gender and Class in the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society ". American Historical Review . 99 (5): 1758. doi:10.1086/ahr/99.5.1758. ISSN 1937-5239.