History

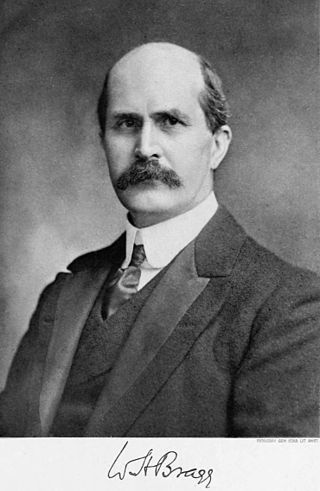

In the early years of World War I submarines were fearful, one-sided weapons because they were invisible. In July 1915 Arthur Balfour replaced Winston Churchill as First Lord of the Admiralty. Balfour appreciated the importance of science, so he established a Board of Invention and Research (BIR), composed of a three-man central committee supported by an eminent consulting panel. [1] The remits of Section II of the panel, the members of which included physicists Ernest Rutherford and William Henry Bragg, included anti-submarine measures. [2] [3] The panel concluded that the most promising approach was to listen for submarines, so they sought to improve hydrophones. Bragg soon moved to the hydrophone research centre HMS Tarlair at Aberdour on the Firth of Forth (which later relocated to Harwich in Essex).

Independently from the BIR, in August 1915, a submerged cable was laid on the seabed of the Firth of Forth. [4] The idea originated with the Scottish physicist Alexander Crichton Mitchell, who was helped by the Royal Navy at HMS Tarlair. [5] He had shown that the passage of a submarine past a cable formed an induction loop which induced a voltage of approximately a millivolt, detectable by a sensitive galvanometer. Voltages were also induced in the cable by random fluctuations in the Earth's magnetic field and electrical noise from the Glasgow tram lines. Mitchell installed an identical loop outside of the channel for vessels, the two loops were connected so that the random fluctuations cancelled each other out. A rheostat was used to give the two loops identical resistances, so that no current flowed until a vessel approached. Unfortunately, his report to the BIR was misunderstood and his findings rejected as of no value. [6] Consequently, there was a hiatus in the installation of loops until their utility was demonstrated beyond question. Under Bragg's leadership, a number were installed. [7] Later in World War I the tiny induced voltages were amplified by vacuum tube amplifiers. Even with that assistance, a long loop installed to monitor traffic in the English Channel proved impractical.

The "Liverpool Cable" used for the loops consisted of four-core, single strand 1.23 mm copper wire, sheathed in two-layer rubber insulation of 3.7 mm diameter, that was wrapped in jute identification tape. The cores were separated by five strands of 36-thread cotton serving, wrapped in two layers of linen identification tape, all encased in a 12.8 mm diameter lead sheath that was wrapped in 18 strands of tarred hemp, and armoured with 26 strand 2.0 mm steel wire, giving a final diameter of 18.8 mm. [8] The cores were wired together when the cable was used for a loop.

A notable operational use of a loop was at the Grand Fleet's anchorage at Scapa Flow. [9] The German submarine UB-116, captained by Lieutenant J J Emsmann, who, along with his crew had volunteered for a suicide mission, was detected by hydrophones at 21:21 on 28 October 1918 while entering the harbour via Hoxa Sound. There were no allied vessels in the harbour so the indicator loops on the minefields were activated. Two hours later, at 23:32, current was detected in an indicator loop laid in a remotely controlled minefield, induced by the submarine as it passed over the cable. Activation of the loop detonated mines in the field, sinking the submarine. [10] UB-116 was the last U-boat destroyed by enemy action before the Armistice, ironically when it had no prey. The wreck of UB-116 was raised in 1919 but foundered while being towed. Its broken-up scraps fell back onto the seabed, where now they are popular with scuba divers. [11]

After the First World War, indicator loop devices were further developed by the Admiralty's research divisions at HMS Vernon and HMS Osprey (Portland Naval Base). In WWII indicator loops were used by the Allies for harbour defence in the UK and its dominions and protectorates, as well as by the US Navy. [12] [13] For example, the Hoxa channel into Scapa Flow was provided with two guard loops followed by eight mine loops in echelon. [14]

An indicator loop gave the first warning of the 1942 attack on Sydney Harbour, when it detected the midget submarine M-14, but that signal was ignored, owing to civilian traffic in the area. The submarine was soon sighted visually, after it became entangled in a submarine net and its bow broke the surface.