Related Research Articles

Svarga, also known as Swarga, Indraloka and Svargaloka, is the celestial abode of the devas in Hinduism. Svarga is one of the seven higher lokas in Hindu cosmology. Svarga is often translated as heaven, though it is regarded to be dissimilar to the concept of the Abrahamic Heaven.

Om is a polysemous symbol representing a sacred sound, syllable, mantra, and invocation in Hinduism. Its written form is the most important symbol in the Hindu religion. It is the essence of the supreme Absolute, consciousness, Ātman,Brahman, or the cosmic world. In Indian religions, Om serves as a sonic representation of the divine, a standard of Vedic authority and a central aspect of soteriological doctrines and practices. It is the basic tool for meditation in the yogic path to liberation. The syllable is often found at the beginning and the end of chapters in the Vedas, the Upanishads, and other Hindu texts. It is described as the goal of all the Vedas.

Vyasa or Veda Vyasa, also known as Krishna Dvaipayana Veda Vyasa, is a rishi (sage) with a prominent role in most Hindu traditions. He is traditionally regarded as the author of the epic Mahābhārata, where he also plays a prominent role as a character. He is also regarded by the Hindu traditions to be the compiler of the mantras of the Vedas into four texts, as well as the author of the eighteen Purāṇas and the Brahma Sutras.

Bhakti yoga, also called Bhakti marga, is a spiritual path or spiritual practice within Hinduism focused on loving devotion towards any personal deity. It is one of the three classical paths in Hinduism which lead to moksha, the other paths being jnana yoga and karma yoga.

Gṛhastha literally means "being in and occupied with home, family" or "householder". It refers to the second phase of an individual's life in a four age-based stages of the Hindu asrama system. It follows celibacy life stage, and embodies a married life, with the duties of maintaining a home, raising a family, educating one's children, and leading a family-centred and a dharmic social life.

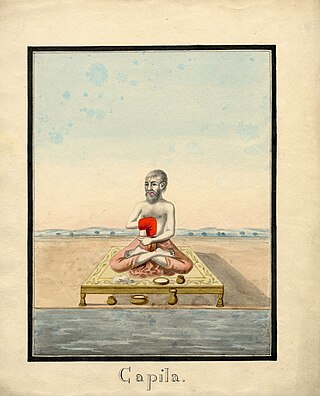

Kapila, also referred to as Cakradhanus, is a Vedic sage in Hindu tradition, regarded the founder of the Samkhya school of Hindu philosophy.

The Yoga Sutras of Patañjali is a compilation "from a variety of sources" of Sanskrit sutras (aphorisms) on the practice of yoga – 195 sutras and 196 sutras. The Yoga Sutras were compiled in India in the early centuries CE by the sage Patanjali, who collected and organized knowledge about yoga from Samkhya, Buddhism, and older Yoga traditions, and possibly another compiler who may have added the fourth chapter. He may also be the author of the Yogabhashya, a commentary on the Yoga Sutras, traditionally attributed to the legendary Vedic sage Vyasa, but possibly forming a joint work of Patanjali called the Pātañjalayogaśāstra.

Varna, in the context of Hinduism, refers to a social class within a hierarchical traditional Hindu society. The ideology of varna is epitomized in texts like Manusmriti, which describes and ranks four varnas, and prescribes their occupations, requirements and duties, or Dharma.

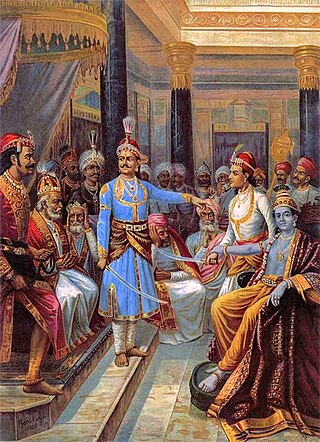

Sanjaya or Sanjaya Gavalgana is a figure from the ancient Indian Hindu epic Mahābhārata. Sanjaya is the advisor of the blind king Dhritarashtra, the ruler of the Kuru kingdom and the father of the Kauravas, as well as serving as his charioteer. Sanjaya is a disciple of Sage Vyasa. He is stated to have the gift of divya drishti, the ability to observe distant events within his mind, granted by Vyasa. He narrates to Dhritarashtra the events of the Kurukshetra War, including the ones described in the Bhagavad Gita.

Karma yoga, also called Karma marga, is one of the three classical spiritual paths mentioned in the Bhagavad Gita, one based on the "yoga of action", the others being Jnana yoga and Bhakti yoga. To a karma yogi, right action is a form of prayer. The paths are not mutually exclusive in Hinduism, but the relative emphasis between Karma yoga, Jnana yoga and Bhakti yoga varies by the individual.

Kashinath Trimbak Telang was an Indologist and Indian judge at Bombay High Court.

Gita Mahotsav,Gita Jayanti, also known as Mokshada Ekadashi or Matsya Dvadashi is a Hindu observance that marks the day the Bhagavad Gita dialogue occurred between Arjuna and Krishna on the battlefield of Kurukshetra. It is celebrated on Shukla Ekadashi, the 11th day of the waxing moon of the lunar month Margashirsha (December–January) of the Hindu calendar.

Dhyāna in Hinduism means meditation and contemplation. Dhyana is taken up in Yoga practices, and is a means to samadhi and self-knowledge.

Adi Shankara, a Hindu philosopher of the Advaita Vedanta school, composed a number of commentarial works. Due to his later influence, a large body of works that is central to the Advaita Vedanta interpretation of the Prasthanatrayi, the canonical texts consisting of the Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita and the Brahma Sutras, is also attributed to him. While his own works mainly consist of commentaries, the later works summarize various doctrines of the Advaita Vedanta tradition, including doctrines that diverge from those of Adi Shankara.

The Udyoga Parva, or the Book of Effort, is the fifth of eighteen books of the Indian epic Mahābhārata. Udyoga Parva traditionally has 10 parts and 199 chapters. The critical edition of Sabha Parva has 12 parts and 197 chapters.

The Bhagavad Gita, often referred to as the Gita, is a Hindu scripture, dated to the second or first century BCE, which forms part of the epic Mahabharata. It is a synthesis of various strands of Indian religious thought, including the Vedic concept of dharma ; samkhya-based yoga and jnana (knowledge); and bhakti (devotion). It holds a unique pan-Hindu influence as the most prominent sacred text and is a central text in Vedanta and the Vaishnava Hindu tradition.

The Sānatsujātiya refers to a portion of the Mahābhārata, a Hindu epic. It appears in the Udyoga Parva (book), and is composed of five chapters. One reason for the Sānatsujātiya's importance is that it was commented upon by Adi Shankara, the preeminent expositor of Advaita Vedanta, and one of the most important Hindu sages, philosophers, and mystics.

Ashvamedhika Parva, is the fourteenth of eighteen books of the Indian epic Mahabharata. It traditionally has 2 parts and 96 chapters. The critical edition has one sub-book and 92 chapters.

References

- 1 2 3 Mahabharata, Hindu Literature, Wendy Doniger, Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ↑ Kashinath T Telang (1882). Max Muller (ed.). The Bhagavadgîtâ: With the Sanatsugâtîya and the Anugîtâ. Clarendon Press. pp. 198–204.

- 1 2 Kashinath T Telang, The Anugita, Volume 8, Sacred Books of the East, Editor: Max Muller, Oxford (Republished by Universal Theosophy)

- ↑ Moriz Winternitz (1996). A History of Indian Literature. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 408–409. ISBN 978-81-208-0264-3.

- ↑ Sharma, Arvind (1978). "The Role of the Anugītā in the Understanding of the Bhagavadgītā". Religious Studies. 14 (2). Cambridge University Press: 261–267. doi:10.1017/s0034412500010738. ISSN 0034-4125. S2CID 169626479.

- ↑ F. Max Muller (2014). The Anugita. Routledge (Reprint of the 1910 Original). pp. 197–227. ISBN 978-1-317-84920-9.

- ↑ F. Max Muller (2014). The Bhagavadgita with the Sanatsujatiya and the Anugita. Routledge (Reprint of the 1910 Original). pp. 261–339. ISBN 978-1-317-84920-9.

- ↑ F. Max Muller (2014). The Bhagavadgita with the Sanatsujatiya and the Anugita. Routledge (Reprint of the 1910 Original). pp. 261–289. ISBN 978-1-317-84920-9.

- ↑ F. Max Muller (2014). The Bhagavadgita with the Sanatsujatiya and the Anugita. Routledge (Reprint of the 1910 Original). pp. 289–291. ISBN 978-1-317-84920-9.

- ↑ F. Max Muller (2014). The Bhagavadgita with the Sanatsujatiya and the Anugita. Routledge (Reprint of the 1910 Original). pp. 311–374. ISBN 978-1-317-84920-9.

- ↑ Herman Tieken (2009), Kill and be Killed: The Bhagavadgita and Anugita in the Mahabharata, Journal of Hindu Studies, Vol. 2 Issue 2 (November), pages 209-228

- ↑ Max Muller (1882). Sacred Books of the East: The Bhagavadgita with the Sanattsugtiya and the Anugita. Clarendon Press. pp. 325–326.

- ↑ Kashinath T Telang (1882). Max Muller (ed.). The Bhagavadgîtâ: With the Sanatsugâtîya and the Anugîtâ. Clarendon Press. pp. 198–207.

- ↑ F. Max Muller (2014). The Bhagavadgita with the Sanatsujatiya and the Anugita. Routledge (Reprint of the 1910 Original). pp. 197, 201–208. ISBN 978-1-317-84920-9.

- ↑ F. Max Muller (2014). The Bhagavadgita with the Sanatsujatiya and the Anugita. Routledge (Reprint of the 1910 Original). pp. 212–226. ISBN 978-1-317-84920-9.

- ↑ Yaroslav Vassilkov (2002), The Gītā versus the Anugītā: Were Yoga and Sāṃkhya Ever Really One? [ dead link ], Epics, Khilas, and Puranas: Continuities and ruptures : proceedings of the Third Dubrovnik International Conference on the Sanskrit Epics and Puranas, pages 221-230, 234-252

Bibliography

- Kashinath Trimbak Telang (translator), The Anugita: Being a Translation of Sanscrit Manuscripts from the Asvameda Paravan of the Mahabharata, and Being a Natural Adjunct to the Bhagavad Gita, Sacred Books of the East, Volume 8