Related Research Articles

The Paus family is a Norwegian family that first appeared as members of the elite of 16th-century Oslo and that for centuries belonged to Norway's "aristocracy of officials" as members of the clergy and legal profession, especially in Upper Telemark. Family members later became involved in shipping, steel and banking. The family is particularly known for its close association with Henrik Ibsen.

The aristocracy of Norway is the modern and medieval aristocracy in Norway. Additionally, there have been economical, political, and military elites that—relating to the main lines of Norway's history—are generally accepted as nominal predecessors of the aforementioned. Since the 16th century, modern aristocracy is known as nobility.

Riksrådet or Rigsrådet is the name of the councils of the Scandinavian countries that ruled the countries together with the kings from late Middle Ages to the 17th century. Norway had a Council of the Realm that was de facto abolished by the Danish-Norwegian king in 1536–1537. In Sweden the parallel Council gradually came under the influence of the king during the 17th century.

Øystein Sørensen is a Norwegian historian. A professor at the University of Oslo since 1996, he has published several books on the history of ideas, including Norwegian nationalism and national socialism, as well as general Norwegian World War II history.

Gentry are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past. Gentry, in its widest connotation, refers to people of good social position connected to landed estates, upper levels of the clergy, or "gentle" families of long descent who in some cases never obtained the official right to bear a coat of arms. The gentry largely consisted of landowners who could live entirely from rental income or at least had a country estate; some were gentleman farmers. In the United Kingdom, the term gentry refers to the landed gentry: the majority of the land-owning social class who typically had a coat of arms but did not have a peerage. The adjective "patrician" describes in comparison other analogous traditional social elite strata based in cities, such as the free cities of Italy and the free imperial cities of Germany, Switzerland, and the Hanseatic League.

Denmark–Norway is a term for the 16th-to-19th-century multi-national and multi-lingual real union consisting of the Kingdom of Denmark, the Kingdom of Norway, the Duchy of Schleswig, and the Duchy of Holstein. The state also claimed sovereignty over three historical peoples: Frisians, Gutes and Wends. Denmark–Norway had several colonies, namely the Danish Gold Coast, the Nicobar Islands, Serampore, Tharangambadi, and the Danish West Indies. The union was also known as the Dano-Norwegian Realm, Twin Realms (Tvillingerigerne) or the Oldenburg Monarchy (Oldenburg-monarkiet).

A state of emergency was declared by the King of Denmark, Frederick III of Denmark in 1660. Its purpose was to put pressure on the nobility of the first estate which in Denmark at the time took the form of the Riksråd, which were reluctant to a proposal from the second (bishoprics) and third estates (burghers) to replace the elective monarchy with hereditary monarchy.

Anton Wilhelm Brøgger was a Norwegian archaeologist and politician.

The Unification of Norway is the process by which Norway merged from several petty kingdoms into a single kingdom, predecessor to the modern Kingdom of Norway.

The Anker family, also spelled Ancher, is a Danish and Norwegian noble family living in Norway. The name means anchor. Originally from Sweden, the family became a part of the Patriciate of Norway in the 18th century, and members of the family were ennobled in 1778. One line of the family living in Mecklenburg became part of the German nobility, but later went extinct.

The Gyldenstjerne family, also spelled Gyldenstierne and in Swedish Gyllenstierna, is a Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish noble family divided into various branches and ranks. It is one of the oldest noble families in Scandinavia. The family surname appears, in the form of Guildenstern, in William Shakespeare's tragedy The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. The surname should not be confused with Gyldensteen, the name of another short-lived Danish noble family, first recorded in 1717 and which became extinct in 1749.

The Nobility Law was passed by the national parliament in Norway, the Storting, on 1 August 1821. It abolished noble titles and privileges within two generations and required legal proof of nobility in the meantime.

The Norwegian patriciate was a social class in Norway from the 17th century until the modern age; it is typically considered to have ended sometime during the 19th or early 20th century as a distinct class. Jørgen Haave defines the Norwegian patriciate as a broad collective term for the civil servants (embetsmenn) and the burghers in the cities who were often merchants or ship's captains, i.e. the non-noble upper class. Thus it corresponds to term patriciate in its modern, broad generic sense in English. The patricians did not constitute a legally defined class as such, although its constituent groups, the civil servants and the burghers held various legal privileges, with the clergy de jure forming one of the two privileged estates of the realm until 1814.

Events in the year 1588 in Norway.

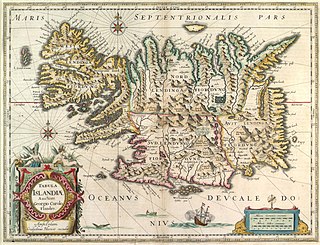

Nobility in Iceland may refer to the following:

The Sovereignty Act or the Absolute and Hereditary Monarchy Act refers to two similar constitutional acts that introduced absolute and hereditary monarchy in the Kingdom of Denmark and absolute monarchy in the Kingdom of Norway, which was already a hereditary monarchy.

Henning Stockfleth was a Norwegian cleric and Bishop of Oslo.

The Stockfleth family is a Dano-Norwegian noble family. Three branches of the family were naturalized as a part of the Danish nobility in 1779, based on a claim that the family had been noble since the time of King Valdemar III (1314–1364).

Sir Peder Povelsson Paus, also rendered as Peter Paus and known locally as Sir Per, was a Norwegian high-ranking cleric who served as the provost of Upper Telemark from 1633 until his death. As provost he was not only the religious leader of the vast region of Upper Telemark, but also one of the foremost government officials in Telemark; during his lifetime the state church was also an important part of the state administration. He is known through a loving poem in Latin written by his son Paul Peterson Paus in his memory in 1653, In memoriam Domini Petri Pavli. His descendants include the playwright Henrik Ibsen and the singer Ole Paus.

Mathia Collett was a Norwegian merchant and businessperson. After her first husband's death, she was the co-owner of the trading company Collett & Leuch, an influential trading company, with her brother. From 1773 to her death in 1801, she was married to the then wealthiest person in Norway, Bernt Anker. She is the younger sister of the poet Ditlevine Feddersen.

References

- 1 2 Haanes, Vidar L. (2007). "Det moderne gjennombrudd i Norge, frikirkeligheten og lavkirkeligheten". Norsk Tidsskrift for Misjonsvitenskap. 61 (1): 3–20. doi:10.48626/ntm.v61i1.4156.

- 1 2 Myhre, Jan Eivind, "Academics as the ruling elite in 19th century Norway," Historical Social Research 33 (2008), 2, pp. 21–41

- ↑ See for example C. Molbech, "Nogle Yttringer om Aristokratie og Adelstand," Historisk Tidsskrift Vol. 3 p. 175, 1842

- 1 2 3 Eliter i Norge i dansketida, Norgeshistorie

- ↑ Lars Løberg, Norsk adel, hadde vi det? Archived 2012-03-21 at the Wayback Machine , Genealogen 2/1998, pp. 29–32.

- ↑ Michael Hoffmann, Prestebilete og prestekvardag, Det teologiske Menighetsfakultet, 2012, p. 23

- ↑ Hegstad, Harald, "Presten og de andre: Ekklesiologiske perspektiver," in Huse, Morten (ed.), Prest og ledelse, Oslo: Verbum, 2000, p. 31

- 1 2 Jens Arup Seip: Fra embedsmannsstat til ettpartistat og andre essays, Universitetsforlaget, 1963

- ↑ Øystein Rian, "Embetsaristokratiet i Norge – en adelsliknende elite," lecture, Den dansk-norske embetsstanden, 14–15 January 2014, Lysebu

- ↑ Øystein Rian, (2014). "Det norske embetsaristokratiet," in Morten Nordhagen Ottosen and Marthe Hommerstad (eds.), Ideal og realitet. 1814 i politisk praksis for folk og elite (pp. 111–125). Akademika forlag. ISBN 978-82-3210-334-8