Salò is a town and comune in the Province of Brescia in the region of Lombardy on the banks of Lake Garda, on which it has the longest promenade. The city was the seat of government of the Italian Social Republic from 1943 to 1945, a state often referred to as the "Salò Republic".

Saint Titian of Brescia was a fifth-century bishop of Brescia. In the list of bishops of Brescia, he is considered the fifteenth bishop of Brescia, succeeding Vigilius and preceding Paul II. His episcopate is believed to have occurred at the end of the fifth century.

The church of Santa Maria dei Miracoli is located on Corso Martiri della Libertà in Brescia.

The church of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Brescia is located on at the west end of Via Elia Capriolo, where it intersects with the Via delle Grazie. Built in the 16th century and remodeled in the 17th century, it still retains much of its artwork by major regional artists, including one of its three canvases by Moretto. The other two are now held at the Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo. The interior is richly decorated in Baroque fashion. Adjacent to the church is the Sanctuary of Santa Maria delle Grazie, a neo-gothic work.

Gasparo Cairano, also known as Gasparo da Cairano, de Cayrano, da Milano, Coirano, and other variations, was an Italian Renaissance sculptor.

Antonio Mangiacavalli was an Italian sculptor of the Renaissance.

Santa Maria Annunziata is the main religious building (duomo) of the town of Salò, Italy.

Antonio della Porta, better known as Tamagnino was an Italian sculptor of the Renaissance.

Bernardino delle Croci was an Italian goldsmith and sculptor of the Brescian Renaissance. He was the founder of the Delle Croci family of important goldsmiths and sculptors, known for their specialism in processional crosses, reliquaries and altars.

Palazzo della Loggia is a Renaissance palace situated in the eponymous piazza in Brescia.

The Caprioli Adoration is an Italian Renaissance sculpture, a relief in marble by Gasparo Cairano, dated between 1495 and 1500, placed in the Church of St Francis of Assisi in Brescia as a frontal for the high altar.

The Tomb of Gaspare Brunelli is a funerary monument in partially painted and gilded marble by Gasparo Cairano, dating to 1500, and situated in the Sacred Heart chapel of the Church of St Francis of Assisi, Brescia.

The Caprioli Chapel is the second chapel on the left side of the nave of the Church of San Giorgio in Brescia.

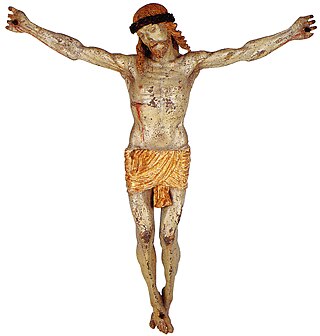

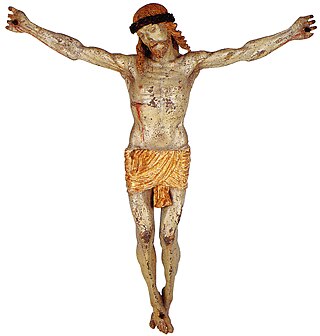

Maffeo Olivieri was an Italian sculptor and wood carver. Often associated with his younger brother Andrea, he was active in Lombardy, Venice and Trentino. He was known for his bronze, wood and marble creations, and considered the premier sculptor in early sixteenth century Brescia.

The Ark of Sant'Apollonio is a funerary monument in marble by Gasparo Cairano. Dated between 1508 and 1510, it is located in the third chapel on the right of the southern nave of the New Cathedral, Brescia.

The Altar of San Girolamo is a sculptural complex in marble, around 780×450×80cm in dimension, designed and constructed by Gasparo Cairano and Antonio Medaglia, and situated within the Church of St Francis of Assisi in Brescia, Italy. Dated between 1506–1510, it is located in the first chapel on the right side of the nave.

The Bergamasque and Brescian Renaissance is one of the main variations of Renaissance art in Italy. The importance of the two cities on the art scene only expanded from the 16th century onward, when foreign and local artists gave rise to an original synthesis of Lombard and Venetian modes, due in part to the two cities' particular geographical position: the last outpost of the Serenissima on the mainland for Bergamo and a disputed territory between Milan and Venice for Brescia.

The Martinengo mausoleum is a funerary monument made through the use of various marbles and bronze by Gasparo Cairano, Bernardino delle Croci and probably the Sanmicheli workshop, dated between 1503 and 1518 and preserved in the museum of Santa Giulia in Brescia, in the nuns' choir.

The intricate critical itinerary of Gasparo Cairano, which began while the sculptor was alive and today is not yet fully concluded after more than five hundred years, has seen the contribution of numerous critical voices and the consequent production of a bibliography that is particularly consistent and varied in content, directed, however, to the almost total misrecognition of the author and his production.

Brescian Renaissance sculpture was an important offshoot of Renaissance sculpture developed in Brescia from around the 1460s within the framework of Venetian culture, peaking between the end of the century and the beginning of the next. In this period, a series of public and private worksites were able to produce absolutely original works, ranging from the refined and experimental sculptural style of the church of Santa Maria dei Miracoli to the regular classicism of the Palazzo della Loggia.