Related Research Articles

Cross-country skiing is a form of skiing where skiers rely on their own locomotion to move across snow-covered terrain, rather than using ski lifts or other forms of assistance. Cross-country skiing is widely practiced as a sport and recreational activity; however, some still use it as a means of transportation. Variants of cross-country skiing are adapted to a range of terrain which spans unimproved, sometimes mountainous terrain to groomed courses that are specifically designed for the sport.

Skiing is the use of skis to glide on snow. Variations of purpose include basic transport, a recreational activity, or a competitive winter sport. Many types of competitive skiing events are recognized by the International Olympic Committee (IOC), and the International Ski Federation (FIS).

Alpine skiing, or downhill skiing, is the pastime of sliding down snow-covered slopes on skis with fixed-heel bindings, unlike other types of skiing, which use skis with free-heel bindings. Whether for recreation or for sport, it is typically practiced at ski resorts, which provide such services as ski lifts, artificial snow making, snow grooming, restaurants, and ski patrol.

The snowplough turn,snowplow turn, or wedge turn is a downhill skiing braking and turning technique. It is the first turn taught to beginners, but still is useful to advanced skiers on steep slopes.

The stem christie or wedge christie, is a type of skiing turn that originated in the mid-1800s in Norway and lasted until the late 1960s. It comprises three steps: 1) forming a wedge by rotating the tail of one ski outwards at an angle to the direction of movement, initiating a change in direction opposite to the stemmed ski, 2) bringing the other ski parallel to the wedged ski, and 3) completing the turn with both skis parallel as they carve an arc, sliding sideways together.

The parallel turn in alpine skiing is a method for turning which rolls the ski onto one edge, allowing it to bend into an arc. Thus bent, the ski follows the turn without sliding. It contrasts with earlier techniques such as the stem Christie, which slides the ski outward from the body ("stemming") to generate sideways force. Parallel turns generate much less friction and are more efficient both in maintaining speed and minimizing skier effort.

Sankt Anton am Arlberg, commonly referred to as St Anton, is a village and ski resort in the Austrian state of Tyrol. It lies in the Tyrolean Alps, with aerial tramways and chairlifts up to 2,811 m (9,222 ft), yielding a vertical drop of 1,507 m (4,944 ft). It is also a popular summer resort among hikers, trekkers and mountaineers.

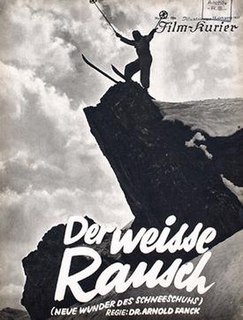

Arnold Fanck was a German film director and pioneer of the mountain film genre. He is best known for the extraordinary alpine footage he captured in such films as The Holy Mountain (1926), The White Hell of Pitz Palu (1929), Storm over Mont Blanc (1930), The White Ecstasy (1931), and S.O.S. Eisberg (1933). Fanck was also instrumental in launching the careers of several filmmakers during the Weimar years in Germany, including Leni Riefenstahl, Luis Trenker, and cinematographers Sepp Allgeier, Richard Angst, Hans Schneeberger, and Walter Riml.

A mountain film is a film genre that focuses on mountaineering and especially the battle of human against nature. In addition to mere adventure, the protagonists who return from the mountain come back changed, usually gaining wisdom and enlightenment.

Johann "Hannes" Schneider was an Austrian ski instructor of the first half of the 20th century, famous for pioneering the Arlberg technique of instruction. Many consider him the Father of Modern Day Skiing. A statue of him in North Conway, New Hampshire, states the very same claim.

A carved turn is a skiing and snowboarding term for the technique of turning by shifting the ski or snowboard onto its edges. When edged, the sidecut geometry causes the ski to bend into an arc, and the ski naturally follows this arc shape to produce a turning motion. The carve is efficient in allowing the skier to maintain speed because, unlike the older stem Christie and parallel turns, the skis don't create drag by sliding sideways.

Otto Lang was a skier and pioneer ski instructor from Bosnia and Herzegovina, who lived and worked in the United States. After teaching skiing at a variety of smaller resorts in Austria, he joined the Hannes Schneider Ski School in St. Anton am Arlberg, one of the most prestigious ski schools of the era. Like many instructors who taught Schneider's Arlberg Method, Lang was eventually offered a chance to teach in the U.S., at Pecketts' on Sugar Hill in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. He later moved out west and founded ski schools on Mount Rainier, Mount Baker and Mount Hood.

The White Ecstasy is a 1931 German mountain film written and directed by Arnold Fanck and starring Hannes Schneider, Leni Riefenstahl, Guzzi Lantschner, and Walter Riml. The film is about the skiing exploits of a young village girl, and her attempts to master the sport of skiing and ski-jumping aided by the local ski expert. Filmed on location in Sankt Anton am Arlberg, the film was one of the first to use and develop outdoor film-making techniques and featured several innovative action-skiing scenes.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to skiing:

Anton "Toni" Matt was an Austrian-American ski pioneer, champion racer, and veteran of the U.S. Army's 10th Mountain Division.

Walter Riml was an Austrian cameraman and actor.

Paula Kann was an Austrian born American alpine skier who represented the United States at the 1948 Winter Olympics in St. Moritz, Switzerland.

This glossary of skiing and snowboarding terms is a list of definitions of terms and jargon used in skiing, snowboarding, and related winter sports.

Stuben am Arlberg is a winter sports resort in the town of Klösterle in the westernmost Austrian province of Vorarlberg. It is located at an altitude of 1,410 meters and had 90 inhabitants.

Olof “Olle” Alfred Rimfors was a Swedish ski pioneer, ski instructor, military officer, and sports official. In 1934 he introduced alpine skiing in Sweden together with Sigge Bergman, after studying for a month at the ski school of Hannes Schneider in St. Anton am Arlberg and competing in the FIS Alpine World Championships.

References

- ↑ Mogul Mick, "Getting Down to Basics", Skiing's Secrets Revealed

- ↑ Lund, Morten (May 1993). The Films of Hannes Schneider. International Skiing History Association. pp. 8–11.

- ↑ Lund, Morten (September 2005). They Taught America to Ski. International Skiing History Association. pp. 19–25.

- ↑ L. Dana, Gatlin (February 1989). Hannes Schneider Arrives. Ski Magazine. pp. 89–98.

- Fanck, Arnold; Schneider, Hannes (1925) Wunder des Schneeschuhs; ein System des richtigen Skilaufens und seine Anwendung im alpinen Geländelauf Hamburg: Gebrüder Enoch OCLC 10252521

- Modern Ski Technique (1931) film

- Schniebs, Otto and McCrillis, John W. (1932) Modern Ski Technique Brattleboro, Vt: Stephen Daye Press OCLC 702560034

- Lang, Otto (1936) Downhill Skiing New York: H. Holt and company OCLC 2105449

- Rybizka, Benno (1938) The Hannes Schneider Ski Technique New York: Harcourt, Brace OCLC 6217443

- The Hannes Schneider Ski Technique (1938) Pathescope film

- Laurie Puliafico, "The Father of Modern Skiing- Hannes Schneider"