The Armenian American lobby is a collection of formal and informal groups and professional lobbyists seeking to influence United States foreign policy in support of Armenia, Armenians or Armenian policies. The purpose and political influence of the lobby has shifted over time, but has included advocacy for Armenian genocide recognition and military support for Armenia. [1]

In 1918, the American Committee for the Independence of Armenia (ACIA) was founded by Vahan Cardashian, the former Consul of the Ottoman Empire in Washington. The organization lobbied on behalf of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF)-governed Republic of Armenia. The ACIA was restructured into the Armenian National Committee of America (ANCA) in 1941. [2]

In 1972, the Armenian Assembly of America was formed as "a new Armenian organization in which leaders from various Armenian groups would participate for the benefit of the community as a whole." The key founding members were contributors to the Armenian General Benevolent Union, the largest remaining non-ARF organization. [3]

In 1982, the ANCA-affiliated [4] Zoryan Institute, a research institute dedicated to scholarship relating to human rights and genocide, [5] was established. The AAA founded the competing Armenian National Institute in 1997, with the goal of raising public awareness of the Armenian Genocide and seeking legal retribution. [6] [7]

The Armenian lobby is almost exclusively formed by lobby groups and associated think tanks such as the Armenian National Committee of America (ANCA) and the Armenian Assembly of America (AAA), leaving the Armenian government largely out of the lobbying process. The two organizations have similar lobbying goals, mostly revolving around improving U.S. relations with Armenia in terms of aid, blocking aid to Turkey and Azerbaijan, as well as their now-accomplished goal of Armenian genocide recognition. However, the two groups provide different approaches to promoting the Armenian cause. The ANCA focuses mostly on grassroots initiatives to mobilize a highly concentrated Armenian electorate. On the other hand, the AAA focuses on retaining large donations from influential Armenians in America. [8] The AAA draws upon the AIPAC model, which is very much centered on influencing foreign policy. [9] The competition between these two groups creates a "hyper-mobilization" of resources in the Armenian community, because the two organizations have similar goals. [10]

The strength of the Armenian lobby can be derived from its concentration in a few congressional districts, such as California's 30th congressional district. [11] In the 2000 census, one-third of the Armenian-American community lived in just 5 districts of the 106th Congress. Half of all Armenian-Americans lived in just 20 congressional districts. [12] This high population concentration allows the Armenian community to greatly sway votes, especially in a time of low voter turnout. One case study of this is when Democratic challenger and current Congressman Adam Schiff won against Republican incumbent Jim Rogan. Schiff effectively captured much of the Armenian vote, and now current champions Armenian issues in Congress. The Armenian community can also draw on its power of partial assimilation—it is not too assimilated like ethnic groups such as German Americans but it has had a presence in the U.S. since the early 1900s. [13]

While the Armenian lobby had been effective in a number of public relations campaigns in the late 20th century, it is now almost completely overshadowed by the Turkish lobby which exaggerated the influence of the Armenian lobby to increase its own lobbying efforts. [14]

Some of its achievements in the second half of the 20th century were $90 million in aid annually for Armenia, the continuation of Section 907 of the Freedom Support Act blocking aid to Azerbaijan, success in stalling an arms deal with Turkey during the 1970s, and US recognition of the Armenian genocide. Armenia received the second highest U.S. aid per capita behind Israel. [15] [ needs update ]

It failed to discourage the US from reducing its financial aid to Armenia while increased aid to Azerbaijan, at a time when Armenia sent soldiers to Iraq and announced it would send soldiers to Afghanistan in support of the US-led campaign. Furthermore, US diplomats have repeatedly asserted that Armenia has to demonstrate flexibility regarding the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict before Turkey can involve itself. [14]

The Armenian lobby has been subdued by the Turkish and Azerbaijani lobbies. In contrast to the Armenian lobby, the Turkish lobby mostly runs through its government. A study on ethnic lobbies and their effect on U.S. foreign policy indicated that the Turkish embassy is more active than Turkish-American organizations in attempting to influence U.S. regional foreign policy. [16] Because the Republic of Turkey cannot legally finance campaigns, it relies on contracting Washington lobbying firms and contacting members of congress and their staff. In 2008, the Turkish government spent $3,524,632 on Washington lobbying activities and contacted members of Congress 2,268 times. Utilizing top lobbying firms such as the Livingston Group, which has represented other Middle Eastern clients such as Egypt and Libya, the Turkish government gained invaluable Washington resources. [17]

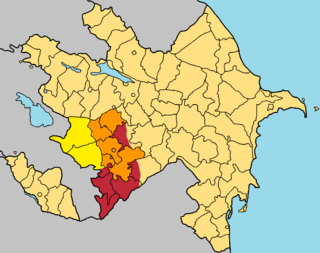

The First Nagorno-Karabakh War was an ethnic and territorial conflict that took place from February 1988 to May 1994, in the enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh in southwestern Azerbaijan, between the majority ethnic Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh backed by Armenia, and the Republic of Azerbaijan with support from Turkey. As the war progressed, Armenia and Azerbaijan, both former Soviet republics, entangled themselves in protracted, undeclared mountain warfare in the mountainous heights of Karabakh as Azerbaijan attempted to curb the secessionist movement in Nagorno-Karabakh.

The Armenian National Committee of America (ANCA) is an Armenian American grassroots organization. Its headquarters is in Washington, D.C., and it has regional offices in Glendale, California, and Watertown, Massachusetts.

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is an ethnic and territorial conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the region of Nagorno-Karabakh, inhabited mostly by ethnic Armenians until 2023, and seven surrounding districts, inhabited mostly by Azerbaijanis until their expulsion during the 1990s. The Nagorno-Karabakh region was entirely claimed by and partially controlled by the breakaway Republic of Artsakh, but was recognized internationally as part of Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan gradually re-established control over Nagorno-Karabakh region and the seven surrounding districts.

Anti-Armenian sentiment, also known as anti-Armenianism and Armenophobia, is a diverse spectrum of negative feelings, dislikes, fears, aversion, racism, derision and/or prejudice towards Armenians, Armenia, and Armenian culture.

Diplomatic relations between Armenia and Turkey are officially non-existent and have historically been hostile. Whilst Turkey recognised Armenia shortly after the latter proclaimed independence in September 1991, it has refused to establish diplomatic relations. In 1993, Turkey reacted to the war in Nagorno-Karabakh by closing its border with Armenia out of support for Azerbaijan, which remain closed to this day despite sporadic negotiations regarding possible opening.

Section 907 of the United States Freedom Support Act bans any kind of direct United States aid to the Azerbaijani government. This ban made Azerbaijan the only post-Soviet state not to receive direct aid from the United States government to facilitate economic and political stability.

United Armenia, also known as Greater Armenia or Great Armenia, is an Armenian ethno-nationalist irredentist concept referring to areas within the traditional Armenian homeland—the Armenian Highland—which are currently or have historically been mostly populated by Armenians. The idea of what Armenians see as unification of their historical lands was prevalent throughout the 20th century and has been advocated by individuals, various organizations and institutions, including the nationalist parties Armenian Revolutionary Federation and Heritage, the ASALA and others.

The Armenian cemetery in Julfa was a cemetery near the town of Julfa, in the Nakhchivan exclave of Azerbaijan that originally housed around 10,000 funerary monuments. The tombstones consisted mainly of thousands of khachkars—uniquely decorated cross-stones characteristic of medieval Christian Armenian art. The cemetery was still standing in the late 1990s, when the government of Azerbaijan began a systemic campaign to destroy the monuments.

The dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991 brought an end to the Cold War and created an opportunity for establishing bilateral relations between the United States with Armenia and other post-Soviet states as they began a political and economic transformation. The United States recognized the independence of Armenia on 25 December 1991, and opened an embassy in Armenia's capital Yerevan in February 1992.

The Madrid Principles were proposed peace settlements of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, proposed by the OSCE Minsk Group. The OSCE Minsk Group was the only internationally agreed body to mediate the negotiations for the peaceful resolution of the conflict prior to the renewed outbreak of hostilities in 2020. Senior Armenian and Azerbaijani officials had agreed on some of the proposed principles but made little or no progress towards the withdrawal of Armenian forces from occupied territories or towards the modalities of the decision on the future Nagorno-Karabakh status.

Foreign relations have reportedly always been strong between Armenia and Cyprus. Cyprus has been a supporter of Armenia in its struggle for the recognition of the Armenian genocide, economic stability and the resolution to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. In return Armenia has been advocating a stable Cyprus after the Turkish invasion in 1974 and supporting a lasting solution to the Cyprus dispute.

The political status of Nagorno-Karabakh remained unresolved from its declaration of independence on 10 December 1991 to its September 2023 collapse. During Soviet times, it had been an ethnic Armenian autonomous oblast of the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, a conflict arose between local Armenians who sought to have Nagorno-Karabakh join Armenia and local Azerbaijanis who opposed this.

Anti-Armenian sentiment or Armenophobia is widespread in Azerbaijan, mainly due to the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh. According to the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI), Armenians are "the most vulnerable group in Azerbaijan in the field of racism and racial discrimination." A 2012 opinion poll found that 91% of Azerbaijanis perceive Armenia as "the biggest enemy of Azerbaijan." The word "Armenian" (erməni) is widely used as an insult in Azerbaijan. Stereotypical opinions circulating in the mass media have their deep roots in the public consciousness.

The following lists events that happened during 2014 in Armenia.

Diplomatic relations between Armenia and Saudi Arabia were formalized on 25 November 2023. Prior to this, the relationship between the two countries has witnessed significant warming since the 2010s, possibly due to common opposition to increasing Turkish influence.

The following is list of the official reactions to the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War.

The Congressional Armenian Caucus (CAC) is an organization of over 100 members of the United States Congress. The Caucus is dedicated to keeping members of Congress engaged on Armenia-related issues as well as strengthening and maintaining the US-Armenia relationship. In particular, the Congressional Armenian Caucus aims to increase US aid to Armenia and Artsakh, recognise the Armenian genocide and to recognise the independence of Artsakh. The CAC was founded in 1995. Although the majority of the members are from the Democratic Party, there are also members from the Republican party including Co-Chairs Gus Bilirakis and David Valadao.

The blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh was an event in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. The region was disputed between Azerbaijan and the breakaway Republic of Artsakh, internationally recognised as part of Azerbaijan, which had an ethnic Armenian population and was supported by neighbouring Armenia, until the dissolution of Republic of Artsakh on 28 September 2023.

Between 19 and 20 September 2023, Azerbaijan launched a large-scale military offensive against the self-declared breakaway state of Artsakh, a move seen as a violation of the ceasefire agreement signed in the aftermath of the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War in 2020. The offensive took place in the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh, which is de jure a part of Azerbaijan, and was a de facto independent republic. The stated goal of the offensive was the complete disarmament and unconditional surrender of Artsakh, as well as the withdrawal of all ethnic Armenian soldiers present in the region. The offensive occurred in the midst of an escalating crisis caused by Azerbaijani Armed Forces blockading Artsakh, which has resulted in significant scarcities of essential supplies such as food, medicine, and other goods in the affected region.

On 19–20 September 2023, Azerbaijan initiated a military offensive in the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region which ended with the surrender of the self-declared Republic of Artsakh and the disbandment of its armed forces. Up until the military assault, the region was internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan but governed and populated by ethnic Armenians.