Related Research Articles

The Security Service, also known as MI5, is the United Kingdom's domestic counter-intelligence and security agency and is part of its intelligence machinery alongside the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), and Defence Intelligence (DI). MI5 is directed by the Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC), and the service is bound by the Security Service Act 1989. The service is directed to protect British parliamentary democracy and economic interests and to counter terrorism and espionage within the United Kingdom (UK).

The Cambridge Spy Ring was a ring of spies in the United Kingdom that passed information to the Soviet Union during World War II and was active from the 1930s until at least into the early 1950s. None of the known members were ever prosecuted for spying. The number and membership of the ring emerged slowly, from the 1950s onwards. The general public first became aware of the conspiracy after the sudden flight of Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess to the Soviet Union in 1951. Suspicion immediately fell on Harold "Kim" Philby, who eventually fled the country in 1963. Following Philby's flight, British intelligence obtained confessions from Anthony Blunt and then John Cairncross, who have come to be seen as the last two of a group of five. Their involvement was kept secret for many years: until 1979 for Blunt, and 1990 for Cairncross. The moniker Cambridge Four evolved to become the Cambridge Five after Cairncross was added.

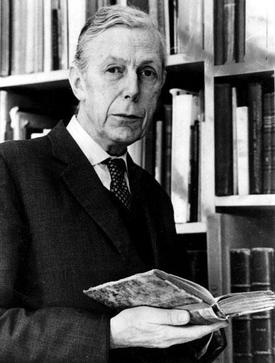

Anthony Frederick Blunt, styled Sir Anthony Blunt KCVO from 1956 to November 1979, was a leading British art historian and Soviet spy.

Nathaniel Mayer Victor Rothschild, 3rd Baron Rothschild was a British banker, scientist, intelligence officer during World War II, and later a senior executive with Royal Dutch Shell and N M Rothschild & Sons, and an advisor to the Edward Heath and Margaret Thatcher governments of the UK. He was a member of the prominent Rothschild family.

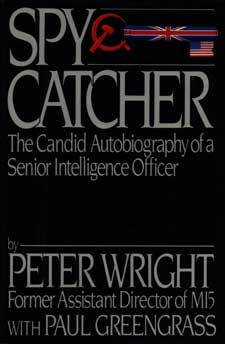

Spycatcher: The Candid Autobiography of a Senior Intelligence Officer (1987) is a memoir written by Peter Wright, former MI5 officer and Assistant Director, and co-author Paul Greengrass. He drew on his own experiences and research into the history of the British intelligence community. Published first in Australia, the book was banned in England due to its allegations about government policy and incidents. These efforts ensured the book's notoriety, and it earned considerable profit for Wright.

Oleg Vladimirovich Penkovsky, codenamed HERO, was a Soviet military intelligence (GRU) colonel during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Penkovsky informed the United States and the United Kingdom about Soviet military secrets, most importantly, the appearance and footprint of Soviet intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) installations and the weakness of the Soviet intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) program. This information was decisive in allowing the US to recognize that the Soviets were placing IRBMs in Cuba before most of the missiles were operational. It also gave US President John F. Kennedy, during the Cuban Missile Crisis that followed, valuable information about Soviet weakness that allowed him to face down Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev and resolve the crisis without a nuclear war.

Peter Maurice Wright CBE was a principal scientific officer for MI5, the British counter-intelligence agency. His book Spycatcher, written with Paul Greengrass, became an international bestseller with sales of over two million copies. Spycatcher was part memoir, part exposé of what Wright claimed were serious institutional failures in MI5 and his subsequent investigations into those. He is said to have been influenced in his counterespionage activity by James Jesus Angleton, the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) counterintelligence chief from 1954 to 1975.

Sir Dick Goldsmith White, was a British intelligence officer. He was Director General (DG) of MI5 from 1953 to 1956, and Head of the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) from 1956 to 1968.

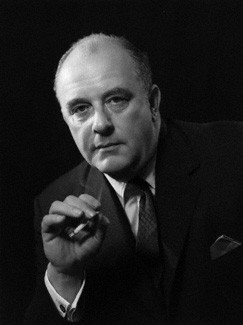

Sir Roger Henry Hollis was a British journalist and intelligence officer who served with MI5 from 1938 to 1965. He was Director General of MI5 from 1956 to 1965.

Henry Chapman Pincher was an English journalist, historian and novelist whose writing mainly focused on espionage and related matters, after some early books on scientific subjects.

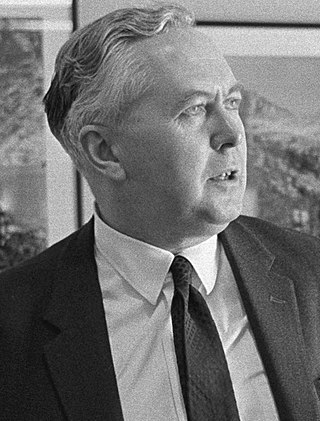

Clockwork Orange was a secret British security services project alleged to have involved a right-wing smear campaign against British politicians from 1974 to 1975. The black propaganda led Prime Minister Harold Wilson to fear that the security services were preparing a coup d'état. The operation takes its name from A Clockwork Orange, a 1971 Stanley Kubrick film based on Anthony Burgess' 1962 novel of the same name.

Since the mid-1970s, a variety of conspiracy theories have emerged regarding British Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson, who served as the prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1964 to 1970 and 1974 to 1976. These range from Wilson having been a Soviet agent, to Wilson being the victim of treasonous plots by conservative-leaning elements in MI5 and the British military, claims which Wilson himself made.

Edward Leadbitter was a British Labour politician. Leadbitter was a teacher, and served as a councillor on West Hartlepool Borough Council.

Bernard Francis Castle Floud was a British farmer, television company executive and politician. He was the father of the economic historian Sir Roderick Floud.

Alister George Douglas Watson was a mathematician who was identified by several writers as a key member of the Cambridge spy ring.

Guy Maynard Liddell, CB, CBE, MC was a British intelligence officer.

Robert Stephen Lipka was a former army clerk at the National Security Agency (NSA) who, in 1997, pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit espionage and was sentenced to 18 years in prison. He was arrested more than 30 years after his betrayal, as there is no statute of limitations for espionage.

Kathleen Maria Margaret Archer MBE was the first female officer in Britain's Security Service, MI5, and was still their only woman officer at the time of her dismissal for insubordination in 1940. She had been responsible for investigations into Soviet intelligence and subversion. She then joined the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), but when Kim Philby, later to be exposed as a double agent, became her boss he reduced her investigative work because he feared she might uncover his treachery.

Graham Russell Mitchell OBE, CB (1905–1984), was an officer of MI5, the British Security Service, between 1939 and 1963, serving as its deputy director general between 1956 and 1963. In 1963 Roger Hollis, the MI5 director general, authorised the secret investigation of Mitchell following suspicions within the Secret Intelligence Service MI6 that he was a Soviet agent. It is now thought unlikely that Mitchell ever was a "mole". Mitchell was an International Master of correspondence chess who represented Great Britain.

Phoebe Pool (1913–1971) was a British art historian and spy for the Soviet Union.

References

- ↑ "All about the Cambridge Spies, by Russell Aiuto". Archived from the original on 13 December 2006. Retrieved 24 December 2006. Russell Aiuto. All about the Cambridge Spies

- ↑ "House of Commons Hansard Debates for 10 Jan 1996 (Pt 43)". Archived from the original on 1 January 2007. Retrieved 24 December 2006. Mr. Ken Livingstone (Brent, East) House of Commons, Hansard Debates for 10 Jan 1996 (pt. 43) : Column 285

- ↑ House of Commons Hansard Debates for 23 Nov 1988

- ↑ House of Commons Hansard Debates for 16 Feb 1989