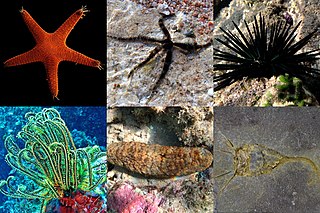

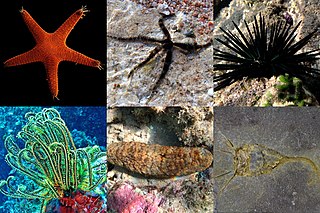

An echinoderm is any deuterostomal animal of the phylum Echinodermata, which includes starfish, brittle stars, sea urchins, sand dollars and sea cucumbers, as well as the sessile sea lilies or "stone lilies". While bilaterally symmetrical as larvae, as adults echinoderms are recognisable by their usually five-pointed radial symmetry, and are found on the sea bed at every ocean depth from the intertidal zone to the abyssal zone. The phylum contains about 7,600 living species, making it the second-largest group of deuterostomes after the chordates, as well as the largest marine-only phylum. The first definitive echinoderms appeared near the start of the Cambrian.

Starfish or sea stars are star-shaped echinoderms belonging to the class Asteroidea. Common usage frequently finds these names being also applied to ophiuroids, which are correctly referred to as brittle stars or basket stars. Starfish are also known as asteroids due to being in the class Asteroidea. About 1,900 species of starfish live on the seabed in all the world's oceans, from warm, tropical zones to frigid, polar regions. They are found from the intertidal zone down to abyssal depths, at 6,000 m (20,000 ft) below the surface.

Brittle stars, serpent stars, or ophiuroids are echinoderms in the class Ophiuroidea, closely related to starfish. They crawl across the sea floor using their flexible arms for locomotion. The ophiuroids generally have five long, slender, whip-like arms which may reach up to 60 cm (24 in) in length on the largest specimens.

Linckia laevigata is a species of sea star in the shallow waters of tropical Indo-Pacific.

The Ophidiasteridae are a family of sea stars with about 30 genera. Occurring both in the Indo-Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, ophidiasterids are greatest in diversity in the Indo-Pacific. Many of the genera in this family exhibit brilliant colors and patterns, which sometimes can be attributed to aposematism and crypsis to protect themselves from predators. Some ophidiasterids possess remarkable powers of regeneration, enabling them to either reproduce asexually or to survive serious damage made by predators or forces of nature. Some species belonging to Linckia, Ophidiaster and Phataria shed single arms that regenerate the disc and the remaining rays to form a complete individual. Some of these also reproduce asexually by parthenogenesis.

Coscinasterias calamaria, or the eleven-armed sea star, is a starfish in the family Asteriidae. It was thought to be endemic to southern Australia and New Zealand but has since been documented as occurring in the Cape Peninsula as well. It is found around low tide levels and deeper, under rocks and wandering over seaweed in pools.

Linckia guildingi, also called the common comet star, Guilding's sea star or the green Linckia, is a species of sea star reported from the shallow waters of the tropical Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean, Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea.

Linckia multifora is a variously colored starfish in the family Ophidiasteridae that is found in the Indian Ocean and Red Sea. Its common names include the Dalmatian Linckia, mottled Linckia, spotted Linckia, multicolor sea star and multi-pore sea star.

Coscinasterias tenuispina is a starfish in the family Asteriidae. It is sometimes called the blue spiny starfish or the white starfish. It occurs in shallow waters in the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea.

Linckia columbiae is a species of starfish in the family Ophidiasteridae. It is found in the East Pacific where it ranges from California (USA) to northwest Peru, including offshore islands such as the Galápagos. Common names include fragile star, Pacific comet sea star and variable sea star.

Nepanthia belcheri is a species of starfish in the family Asterinidae. It is found in shallow water in Southeast Asia and northeastern Australia. It is an unusual species in that it can reproduce sexually or can split in two by fission to form two new individuals. As a result, it has varying numbers of arms, and Hubert Lyman Clark, writing in 1938, stated, "It is a literal truth that no two of the 56 specimens at hand, nearly all from Lord Howe Island, are exactly alike in number, size and form of arms".

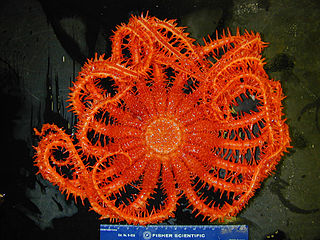

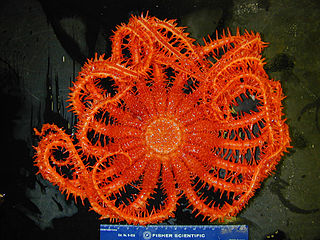

The Brisingidae are a family of starfish found only in the deep sea. They inhabit both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans at abyssal depths, and also occur in the Southern Ocean and around Antarctica at slightly shallower depths.

The Freyellidae are a family of deep-sea-dwelling starfish. It is one of two families in the order Brisingida. The majority of species in this family are found in Antarctic waters and near Australia. Other species have been found near New Zealand and the United States.

Aquilonastra conandae is a species of starfish from the family Asterinidae found near the Mascarene Islands in the Indian Ocean. It is known for its asexual reproduction and is fissiparous. It is a small starfish, discrete and camouflaged, and occurs in coral reefs in the surf zone of large waves. The species was described in 2006 by Australian marine biologists P. Mark O'Loughlin and Francis Winston Edric Rowe, and gets its name from Chantal Conand.

Aquilonastra burtoni is a species of small sea star from the family Asterinidae from the Red Sea which has colonised the eastern Mediterranean by Lessepsian migration through the Suez Canal, although the Mediterranean populations are clonal reproducing through fissiparous asexual reproduction. It was originally described in 1840 by the English zoologist and philatelist John Edward Gray.

Neoferdina cumingi, also known as Cuming's sea star, is a species of starfish in the family Goniasteridae. It is native to the tropical Indo-Pacific region.

Echinaster luzonicus, the Luzon sea star, is a species of starfish in the family Echinasteridae, found in shallow parts of the western Indo-Pacific region. It sometimes lives symbiotically with a copepod or a comb jelly, and is prone to shed its arms, which then regenerate into new individuals.

Henricia sexradiata is a species of starfish in the family Echinasteridae. It is native to the western Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico.

Coscinasterias muricata is a species of starfish in the family Asteriidae. It is a large 11-armed starfish and occurs in shallow waters in the temperate western Indo-Pacific region.

Starfish, or sea stars, are radially symmetrical, star-shaped organisms of the phylum Echinodermata and the class Asteroidea. Aside from their distinguished shape, starfish are most recognized for their remarkable ability to regenerate, or regrow, arms and, in some cases, entire bodies. While most species require the central body to be intact in order to regenerate arms, a few tropical species can grow an entirely new starfish from just a portion of a severed limb. Starfish regeneration across species follows a common three-phase model and can take up to a year or longer to complete. Though regeneration is used to recover limbs eaten or removed by predators, starfish are also capable of autotomizing and regenerating limbs to evade predators and reproduce.