A shekel or sheqel is an ancient Mesopotamian coin, usually of silver. A shekel was first a unit of weight—very roughly 11 grams —and became currency in ancient Tyre, Carthage and Hasmonean Judea.

The history of ancient Greek coinage can be divided into four periods: the Archaic, the Classical, the Hellenistic and the Roman. The Archaic period extends from the introduction of coinage to the Greek world during the 7th century BC until the Persian Wars in about 480 BC. The Classical period then began, and lasted until the conquests of Alexander the Great in about 330 BC, which began the Hellenistic period, extending until the Roman absorption of the Greek world in the 1st century BC. The Greek cities continued to produce their own coins for several more centuries under Roman rule. The coins produced during this period are called Roman provincial coins or Greek Imperial Coins.

The talent was a unit of weight used in the ancient world, often used for weighing gold and silver, but also mentioned in connection with other metals, ivory, and frankincense. In Homer's poems, it is always used of gold and is thought to have been quite a small weight of about 8.5 grams (0.30 oz), approximately the same as the later gold stater coin or Persian daric.

The stater was an ancient coin used in various regions of Greece. The term is also used for similar coins, imitating Greek staters, minted elsewhere in ancient Europe.

The Attic talent, also known as the Athenian talent or Greek talent, is an ancient unit of weight equal to about 26 kilograms (57 lb), as well as a unit of value equal to this amount of pure silver. A talent was originally intended to be the mass of water required to fill an amphora, about one cubic foot (28 L).

Silver coins are one of the oldest mass-produced form of coinage. Silver has been used as a coinage metal since the times of the Greeks; their silver drachmas were popular trade coins. The ancient Persians used silver coins between 612–330 BC. Before 1797, British pennies were made of silver.

The cistophorus was a coin of ancient Pergamum. It was introduced shortly before 190 B.C. at that city to provide the Attalid kingdom with a substitute for Seleucid coins and the tetradrachms of Philetairos. It also came to be used by a number of other cities that were under Attalid control. These cities included Alabanda and Kibyra. It continued to be minted and circulated by the Romans with different coin types and legends down to the time of Septimius Severus, long after the kingdom was bequeathed to Rome. It owes its name to a figure, on the obverse, of the sacred chest of Dionysus.

The Achaemenid Empire issued coins from 520 BC–450 BC to 330 BC. The Persian daric was the first gold coin which, along with a similar silver coin, the siglos represented the first bimetallic monetary standard. It seems that before the Persians issued their own coinage, a continuation of Lydian coinage under Persian rule is likely. Achaemenid coinage includes the official imperial issues, as well as coins issued by the Achaemenid provincial governors (satraps), such as those stationed in Asia Minor.

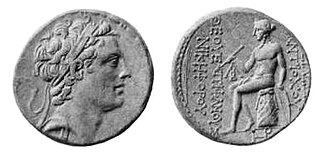

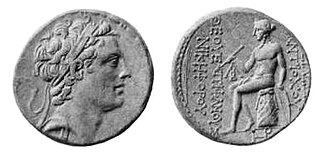

The coinage of the Seleucid Empire is based on the coins of Alexander the Great, which in turn were based on Athenian coinage of the Attic weight. Many mints and different issues are defined, with mainly base and silver coinage being in abundance. A large concentration of mints existed in the Seleucid Syria, as the Mediterranean parts of the empire were more reliant on coinage in economic function.

The coinage of Nabataea began under the reign of Aretas II, c. 110 – 96 BC but it was his heir Aretas III, who at the time was in control of land extending to Damascus. The silver coinage is based on the weight of the Roman Denarius or Greek Drachma, as the adjacent areas around Nabataea used the Greek weight system, it is presumed the coins are of this standard. The local name of the denominations are not known so the Latin denarius and Greek drachma equivalents are used interchangeably.

The tetradrachm was a large silver coin that originated in Ancient Greece. It was nominally equivalent to four drachmae. Over time the tetradrachm effectively became the standard coin of the Antiquity, spreading well beyond the borders of the Greek World. As a result, tetradrachms were minted in vast quantities by various polities in many weight and fineness standards, though the Athens-derived Attic standard of about 17.2 grams was the most common.

The Yehud coinage is a series of small silver coins bearing the Aramaic inscription Yehud. They derive their name from the inscription YHD (𐤉𐤄𐤃), "Yehud", the Aramaic name of the Achaemenid Persian province of Yehud; others are inscribed YHDH, the same name in Hebrew. The minting of Yehud coins commenced around the middle of the fourth century BC, and continued until the end of the Ptolemaic period.

The Athenian coinage decree also known as the Standards decree was a decree made by the Athenians to standardise currency amongst the states with whom they were allied. Between the years of 450 and 447 BC, the use of Athenian silver currency and Athenian weights and measures was made obligatory in all allied states of the Athenian Empire.

In ancient Greece, the drachma was an ancient currency unit issued by many city-states during a period of ten centuries, from the Archaic period throughout the Classical period, the Hellenistic period up to the Roman period. The ancient drachma originated in Greece around the 6th century BC. The coin, usually made of silver or sometimes gold had its origins in a bartering system that referred to a drachma as a handful of wooden spits or arrows. The drachma was unique to each city state that minted them, and were sometimes circulated all over the Mediterranean. The coinage of Athens was considered to be the strongest and became the most popular.

Coinage of the Ptolemaic kingdom was struck in Phoenician weight, also known as Ptolemaic weight which was the weight of a Ptolemaic tetradrachm. This standard, which was not used elsewhere in the Hellenistic world, was smaller than the dominant Attic weight which was the weight of standard Hellenistic tetradrachm. Consequentially, Ptolemaic coins are smaller than other Hellenistic coinage. In terms of art, the coins, which were made of silver, followed the example set by contemporary Greek currencies, with dynastic figures being typically portrayed. The Ptolemaic coin making process often resulted in a central depression, similar to what can be found on Seleucid coinage.

Ancient Rhodian coinage refers to the coinage struck by an independent Rhodian polity during Classical and Hellenistic eras. The Rhodians also controlled territory on neighbouring Caria that was known as Rhodian Peraia under the islanders' rule. However, many other eastern Mediterranean states and polities adopted the Rhodian (Chian) monetary standard following Rhodes. Coinage using the standard achieved a wide circulation in the region. Even the Ptolemaic Kingdom, a major Hellenistic state in the eastern Mediterranean, briefly adopted the Rhodian monetary standard.

Greek coinage of Italy and Sicily originated from local Italiotes and Siceliotes who formed numerous city states. These Hellenistic communities descended from Greek migrants. Southern Italy was so thoroughly hellenized that it was known as the Magna Graecia. Each of the polities struck their own coinage.

A Münzfuß is an historical term, used especially in the Holy Roman Empire, for an official minting or coinage standard that determines how many coins of a given type were to be struck from a specified unit of weight of precious metal. The Münzfuß, or Fuß ("foot") for short in numismatics, determined a coin's fineness, i.e. how much of a precious metal it would contain. Mintmaster Julian Eberhard Volckmar Claus defined the standard in his 1753 work, Kurzgefaßte Anleitung zum Probieren und Münzen, as follows: "The appropriate proportion of metals and the weight of the coin, measured according to their internal and external worth, or determined according to their quality, additives and fineness, number and weight, is called the Münzfuß."

Wappenmünzen are the earliest attested form of Athenian coinage, minted in Ancient Athens under the Peisistratids during the late 6th century BCE. The term refers to an array of silver and electrum coinage minted prior to the use of the Owl of Athena, an emblematic design used on all later Athenian coinage. Initially interpreted by numismatists as the heraldic devices of Athenian noble families, the varied designs of the wappenmünzen are now generally thought to represent individual mint magistrates, in line with contemporary practices in East Greek coinage. In contrast to later Athenian silver coins, the wappenmünzen were minted from imported silver, predating the Classical expansion of the Laurion Mines.