Disposable income is total personal income minus current taxes on income. In national accounts definitions, personal income minus personal current taxes equals disposable personal income. Subtracting personal outlays yields personal savings, hence the income left after paying away all the taxes is referred to as disposable income.

In economics, the fiscal multiplier is the ratio of change in national income arising from a change in government spending. More generally, the exogenous spending multiplier is the ratio of change in national income arising from any autonomous change in spending. When this multiplier exceeds one, the enhanced effect on national income may be called the multiplier effect. The mechanism that can give rise to a multiplier effect is that an initial incremental amount of spending can lead to increased income and hence increased consumption spending, increasing income further and hence further increasing consumption, etc., resulting in an overall increase in national income greater than the initial incremental amount of spending. In other words, an initial change in aggregate demand may cause a change in aggregate output that is a multiple of the initial change.

The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money is a book by English economist John Maynard Keynes published in February 1936. It caused a profound shift in economic thought, giving macroeconomics a central place in economic theory and contributing much of its terminology – the "Keynesian Revolution". It had equally powerful consequences in economic policy, being interpreted as providing theoretical support for government spending in general, and for budgetary deficits, monetary intervention and counter-cyclical policies in particular. It is pervaded with an air of mistrust for the rationality of free-market decision making.

In economics, aggregate demand (AD) or domestic final demand (DFD) is the total demand for final goods and services in an economy at a given time. It is often called effective demand, though at other times this term is distinguished. This is the demand for the gross domestic product of a country. It specifies the amount of goods and services that will be purchased at all possible price levels. Consumer spending, investment, corporate and government expenditure, and net exports make up the aggregate demand.

The marginal propensity to save (MPS) is the fraction of an increase in income that is not spent and instead used for saving. It is the slope of the line plotting saving against income. For example, if a household earns one extra dollar, and the marginal propensity to save is 0.35, then of that dollar, the household will spend 65 cents and save 35 cents. Likewise, it is the fractional decrease in saving that results from a decrease in income.

Consumption is the act of using resources to satisfy current needs and wants. It is seen in contrast to investing, which is spending for acquisition of future income. Consumption is a major concept in economics and is also studied in many other social sciences.

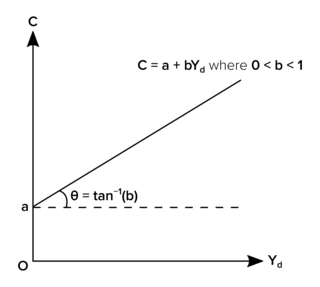

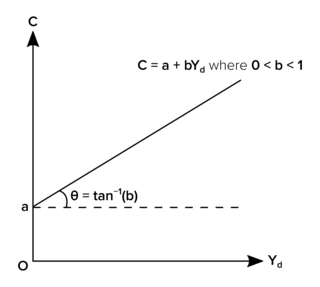

In economics, the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) is a metric that quantifies induced consumption, the concept that the increase in personal consumer spending (consumption) occurs with an increase in disposable income. The proportion of disposable income which individuals spend on consumption is known as propensity to consume. MPC is the proportion of additional income that an individual consumes. For example, if a household earns one extra dollar of disposable income, and the marginal propensity to consume is 0.65, then of that dollar, the household will spend 65 cents and save 35 cents. Obviously, the household cannot spend more than the extra dollar. If the extra money accessed by the individual gives more economic confidence, then the MPC of the individual may well exceed 1, as they may borrow or utilise savings.

In economics, the consumption function describes a relationship between consumption and disposable income. The concept is believed to have been introduced into macroeconomics by John Maynard Keynes in 1936, who used it to develop the notion of a government spending multiplier.

In macroeconomics, automatic stabilizers are features of the structure of modern government budgets, particularly income taxes and welfare spending, that act to damp out fluctuations in real GDP.

Autonomous consumption is the consumption expenditure that occurs when income levels are zero. Such consumption is considered autonomous of income only when expenditure on these consumables does not vary with changes in income; generally, it may be required to fund necessities and debt obligations. If income levels are actually zero, this consumption counts as dissaving, because it is financed by borrowing or using up savings. Autonomous consumption contrasts with induced consumption, in that it does not systematically fluctuate with income, whereas induced consumption does. The two are related, for all households, through the consumption function:

Induced consumption is the portion of consumption that varies with disposable income. When a change in disposable income “induces” a change in consumption on goods and services, then that changed consumption is called “induced consumption”. In contrast, expenditures for autonomous consumption do not vary with income. For instance, expenditure on a consumable that is considered a normal good would be considered to be induced.

The marginal propensity to import (MPM) is the fractional change in import expenditure that occurs with a change in disposable income. For example, if a household earns one extra dollar of disposable income, and the marginal propensity to import is 0.2, then the household will spend 20 cents of that dollar on imported goods and services.

The permanent income hypothesis (PIH) is a model in the field of economics to explain the formation of consumption patterns. It suggests consumption patterns are formed from future expectations and consumption smoothing. The theory was developed by Milton Friedman and published in his A Theory of the Consumption Function, published in 1957 and subsequently formalized by Robert Hall in a rational expectations model. Originally applied to consumption and income, the process of future expectations is thought to influence other phenomena. In its simplest form, the hypothesis states changes in permanent income, rather than changes in temporary income, are what drive changes in consumption.

In Keynesian economics, the average propensity to save (APS), also known as the savings ratio, is the proportion of income which is saved, usually expressed for household savings as a fraction of total household disposable income (taxed income).

The complex multiplier is the multiplier principle in Keynesian economics. The simplistic multiplier that is the reciprocal of the marginal propensity to save is a special case used for illustrative purposes only. The multiplier applies to any change in autonomous expenditure, in other words, an externally induced change in consumption, investment, government expenditure or net exports. Each of these operates to increase or reduce the equilibrium level of income in the economy.

Consumption smoothing is an economic concept for the practice of optimizing a person's standard of living through an appropriate balance between savings and consumption over time. An optimal consumption rate should be relatively similar at each stage of a person's life rather than fluctuate wildly. Luxurious consumption at an old age does not compensate for an impoverished existence at other stages in one's life.

In macroeconomics, a multiplier is a factor of proportionality that measures how much an endogenous variable changes in response to a change in some exogenous variable.

The Keynesian cross diagram is a formulation of the central ideas in Keynes' General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. It first appeared as a central component of macroeconomic theory as it was taught by Paul Samuelson in his textbook, Economics: An Introductory Analysis. The Keynesian cross plots aggregate income and planned total spending or aggregate expenditure.

In economics, the absolute income hypothesis concerns how a consumer divides their disposable income between consumption and saving. It is part of the theory of consumption proposed by economist John Maynard Keynes. The hypothesis was subject to further research in the 1960s and 70s, most notably by American economist James Tobin (1918–2002).

Luigi L. Pasinetti was an Italian economist of the post-Keynesian school. Pasinetti was considered the heir of the "Cambridge Keynesians" and a student of Piero Sraffa and Richard Kahn. Along with them, as well as Joan Robinson, he was one of the prominent members on the "Cambridge, UK" side of the Cambridge capital controversy. His contributions to economics include developing the analytical foundations of neo-Ricardian economics, including the theory of value and distribution, as well as work in the line of Kaldorian theory of growth and income distribution. He also developed the theory of structural change and economic growth, structural economic dynamics and uneven sectoral development.