The Mariana Trench is an oceanic trench located in the western Pacific Ocean, about 200 kilometres (124 mi) east of the Mariana Islands; it is the deepest oceanic trench on Earth. It is crescent-shaped and measures about 2,550 km (1,580 mi) in length and 69 km (43 mi) in width. The maximum known depth is 10,984 ± 25 metres at the southern end of a small slot-shaped valley in its floor known as the Challenger Deep. If Mount Everest were placed into the trench at this point, its peak would still be underwater by more than 2 kilometres (1.2 mi).

Oceanography, also known as oceanology and ocean science, is the scientific study of the oceans. It is an Earth science, which covers a wide range of topics, including ecosystem dynamics; ocean currents, waves, and geophysical fluid dynamics; plate tectonics and the geology of the sea floor; and fluxes of various chemical substances and physical properties within the ocean and across its boundaries. These diverse topics reflect multiple disciplines that oceanographers utilize to glean further knowledge of the world ocean, including astronomy, biology, chemistry, climatology, geography, geology, hydrology, meteorology and physics. Paleoceanography studies the history of the oceans in the geologic past. An oceanographer is a person who studies many matters concerned with oceans, including marine geology, physics, chemistry and biology.

The Challenger expedition of 1872–1876 was a scientific programme that made many discoveries to lay the foundation of oceanography. The expedition was named after the naval vessel that undertook the trip, HMS Challenger.

Edward Forbes FRS, FGS was a Manx naturalist. In 1846, he proposed that the distributions of montane plants and animals had been compressed downslope, and some oceanic islands connected to the mainland, during the recent ice age. This mechanism, which was the first natural explanation to explain the distributions of the same species on now-isolated islands and mountain tops, was discovered independently by Charles Darwin, who credited Forbes with the idea. He also incorrectly deduced the so-called azoic hypothesis, that life under the sea would decline to the point that no life forms could exist below a certain depth.

Sir Charles Wyville Thomson was a Scottish natural historian and marine zoologist. He served as the chief scientist on the Challenger expedition; his work there revolutionized oceanography and led to his being knighted.

Michael Sars was a Norwegian theologian and biologist.

Biological oceanography is the study of how organisms affect and are affected by the physics, chemistry, and geology of the oceanographic system. Biological oceanography may also be referred to as ocean ecology, in which the root word of ecology is Oikos (oικoσ), meaning ‘house’ or ‘habitat’ in Greek. With that in mind, it is of no surprise then that the main focus of biological oceanography is on the microorganisms within the ocean; looking at how they are affected by their environment and how that affects larger marine creatures and their ecosystem. Biological oceanography is similar to marine biology, but is different because of the perspective used to study the ocean. Biological oceanography takes a bottom-up approach, while marine biology studies the ocean from a top-down perspective. Biological oceanography mainly focuses on the ecosystem of the ocean with an emphasis on plankton: their diversity ; their productivity and how that plays a role in the global carbon cycle; and their distribution.

Deep-sea exploration is the investigation of physical, chemical, and biological conditions on the ocean waters and sea bed beyond the continental shelf, for scientific or commercial purposes. Deep-sea exploration is an aspect of underwater exploration and is considered a relatively recent human activity compared to the other areas of geophysical research, as the deeper depths of the sea have been investigated only during comparatively recent years. The ocean depths still remain a largely unexplored part of the Earth, and form a relatively undiscovered domain.

The Endeavour Strait is a strait running between the Australian mainland Cape York Peninsula and Prince of Wales Island in the extreme south of the Torres Strait, in northern Queensland, Australia. It was named in 1770 by explorer James Cook, after his own vessel, HMS Endeavour, and he used the strait as passage out to the Indian Ocean on his voyage.

In zoology, deep-sea gigantism or abyssal gigantism is the tendency for species of invertebrates and other deep-sea dwelling animals to be larger than their shallower-water relatives across a large taxonomic range. Proposed explanations for this type of gigantism include colder temperature, food scarcity, reduced predation pressure and increased dissolved oxygen concentrations in the deep sea. The inaccessibility of abyssal habitats has hindered the study of this topic.

A deep-sea community is any community of organisms associated by a shared habitat in the deep sea. Deep sea communities remain largely unexplored, due to the technological and logistical challenges and expense involved in visiting this remote biome. Because of the unique challenges, it was long believed that little life existed in this hostile environment. Since the 19th century however, research has demonstrated that significant biodiversity exists in the deep sea.

The Hellenic Trench (HT) is an oceanic trough located in the forearc of the Hellenic Arc, an arcuate archipelago on the southern margin of the Aegean Sea Plate, or Aegean Plate, also called Aegea, the basement of the Aegean Sea. The HT begins in the Ionian Sea near the mouth of the Gulf of Corinth and curves to the south, following the margin of the Aegean Sea. It passes close to the south shore of Crete and ends near the island of Rhodes just offshore Anatolia.

The marine biology dredge is used to sample organisms living on a rocky bottom or burrowing within the smooth muddy floor of the ocean (benthic) species. The dredge is pulled by a boat and operates at any depth on a cable or line, generally with a hydraulic winch. The dredge digs into the ocean floor and bring the animals to the surface where they are caught in a net that either follows behind or is a part of the digging apparatus.

Thomas Graves was an officer of the Royal Navy and naturalist who worked extensively as a surveyor in the Mediterranean.

Compression arthralgia is pain in the joints caused by exposure to high ambient pressure at a relatively high rate of compression, experienced by underwater divers. Also referred to in the U.S. Navy Diving Manual as compression pains.

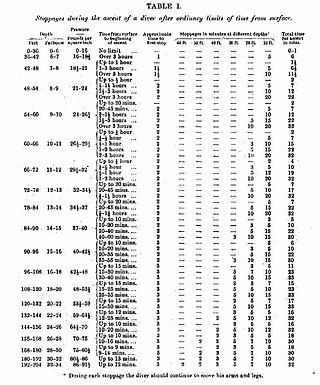

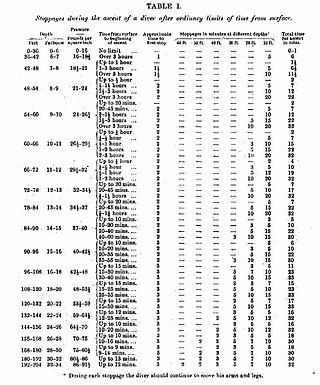

Haldane's decompression model is a mathematical model for decompression to sea level atmospheric pressure of divers breathing compressed air at ambient pressure that was proposed in 1908 by the Scottish physiologist, John Scott Haldane, who was also famous for intrepid self-experimentation.

The Valdivia Expedition, or Deutsche Tiefsee-Expedition, was a scientific expedition organised and funded by the German Empire under Kaiser Wilhelm II and was named after the ship which was bought and outfitted for the expedition, the SS Valdivia. It was led by the marine biologist Carl Chun and the expedition ran from 1898-1899 with the purpose of exploring the depths of the oceans below 500 fathoms, which had not been explored by the earlier Challenger Expedition.

HMS Porcupine was a Royal Navy 3-gun wooden paddle steamer. It was built in Deptford Dockyard in 1844 and served as a survey ship. It was first employed in the survey of the Thames Estuary by Captain Frederick Bullock.

HMS Lightning, launched in 1823, was a paddle steamer, one of the first steam-powered ships on the Navy List. She served initially as a packet ship, but was later converted into an oceanographic survey vessel.

Edward Killwick Calver was a Captain in the Royal Navy, and hydrographic surveyor. He is particularly noted for his surveying work in the east of Britain, and as the captain of HMS Porcupine, in oceanographic voyages in 1869 and 1870.