Related Research Articles

In Greek mythology, the Minotaur is a mythical creature portrayed during classical antiquity with the head and tail of a bull and the body of a man or, as described by Roman poet Ovid, a being "part man and part bull". He dwelt at the center of the Labyrinth, which was an elaborate maze-like construction designed by the architect Daedalus and his son Icarus, upon command of King Minos of Crete. The Minotaur was eventually killed by the Athenian hero Theseus.

Theseus was a divine hero and the founder of Athens from Greek mythology. The myths surrounding Theseus, his journeys, exploits, and friends, have provided material for storytelling throughout the ages.

Hero and Leander is the Greek myth relating the story of Hero, a priestess of Aphrodite who dwelt in a tower in Sestos on the European side of the Hellespont, and Leander, a young man from Abydos on the opposite side of the strait. Leander falls in love with Hero and swims every night across the Hellespont to spend time with her. Hero lights a lamp at the top of her tower to guide his way.

In Greek mythology, Phaedra was a Cretan princess. Her name derives from the Greek word φαιδρός, which means "bright". According to legend, she was the daughter of Minos and Pasiphaë, and the wife of Theseus. Phaedra fell in love with her stepson Hippolytus. After he rejected her advances, she accused him of trying to rape her, causing Theseus to pray to Poseidon to kill him, and then killed herself.

In Greek mythology, Ariadne was a Cretan princess and the daughter of King Minos of Crete. There are different variations of Ariadne's myth, but she is known for helping Theseus escape the Minotaur and being abandoned by him on the island of Naxos. There, Dionysus saw Ariadne sleeping, fell in love with her, and later married her. Many versions of the myth recount Dionysus throwing Ariadne's jeweled crown into the sky to create a constellation, the Corona Borealis.

James Henry Leigh Hunt, best known as Leigh Hunt, was an English critic, essayist and poet.

Phyllis is a character in Greek mythology, daughter of a Thracian king. She marries Demophon, King of Athens and son of Theseus, while he stops in Thrace on his journey home from the Trojan War.

Hero and Leander is a poem by Christopher Marlowe that retells the Greek myth of Hero and Leander. After Marlowe's untimely death, it was completed by George Chapman. The minor poet Henry Petowe published an alternative completion to the poem. The poem was first published five years after Marlowe's demise.

Catullus 64 is an epyllion or "little epic" poem written by Latin poet Catullus. Catullus' longest poem, it retains his famed linguistic witticisms while employing an appropriately epic tone.

Bacchus and Ariadne (1522–1523) is an oil painting by Titian. It is one of a cycle of paintings on mythological subjects produced for Alfonso I d'Este, Duke of Ferrara, for the Camerino d'Alabastro – a private room in his palazzo in Ferrara decorated with paintings based on classical texts. An advance payment was given to Raphael, who originally held the commission for the subject of a Triumph of Bacchus.

L'Arianna is the lost second opera by Italian composer Claudio Monteverdi. One of the earliest operas in general, it was composed in 1607–1608 and first performed on 28 May 1608, as part of the musical festivities for a royal wedding at the court of Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga in Mantua. All the music is lost apart from the extended recitative known as "Lamento d'Arianna". The libretto, which survives complete, was written in eight scenes by Ottavio Rinuccini, who used Ovid's Heroides and other classical sources to relate the story of Ariadne's abandonment by Theseus on the island of Naxos and her subsequent elevation as bride to the god Bacchus.

Hero and Leander is a poem by Leigh Hunt written and published in 1819. The result of three years of work, the poem tells the Greek myth of Hero and Leander, two lovers, and the story of their forlorn fate. Hunt began working on the poem during the summer of 1816, arousing the interest of the publisher John Taylor, and despite repeated delays to allow Hunt to deal with other commitments the poem was finished and published in a collection 1819. Dealing with themes of love and its attempt to conquer nature, the poem does not contain the political message that many of Hunt's works around that time do. The collection was well received by contemporary critics, who remarked on its sentiment and delicacy, while more modern writers such as Edmund Blunden have criticised the flow of its narrative.

Juvenilia; or, a Collection of Poems Written between the ages of Twelve and Sixteen by J. H. L. Hunt, Late of the Grammar School of Christ's Hospital, commonly known as Juvenilia, was a collection of poems written by James Henry Leigh Hunt at a young age and published in March 1801. As an unknown author, Hunt's work was not accepted by any professional publishers, and his father Isaac Hunt instead entered into an agreement with the printer James Whiting to have the collection printed privately. The collection had over 800 subscribers, including important academics, politicians and lawyers, and even people from the United States. The critical and public response to Hunt's work was positive; by 1803 the collection had run into four volumes. The Monthly Mirror declared the collection to show "proofs of poetic genius, and literary ability", and Edmund Blunden held that the collection acted as a predictor of Hunt's later success. Hunt himself came to despise the collection as "a heap of imitations, all but absolutely worthless", but critics have argued that without this early success to bolster his confidence Hunt's later career could have been far less successful.

The Palace of Pleasure is a poem by James Henry Leigh Hunt published in his 1801 collection Juvenilia. Written before he was even sixteen, the work was part of a long tradition of poets imitating Spenser. The Palace of Pleasure is an allegory based on Book II of Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene and describes the adventure of Sir Guyon as he is taken by airy sylphs to the palace of the "Fairy Pleasure". According to Hunt the poem "endeavours to correct the vices of the age, by showing the frightful landscape that terminates the alluring path of sinful Pleasure".

The Literary Pocket-Book was a collection of works edited by Leigh Hunt and containing material by Hunt, Percy Bysshe Shelley, John Keats, and Bryan Waller Procter. The collection was put together during 1818, and proved so successful that Hunt was able to sell the copyright for £200 a year later. The collection includes written worked, lined pages to write notes on and lists of authors, artists, schools and libraries. It was a public success, bringing new readers to both Shelley and Keats, and served as a model for other collections of poetry written during the Victorian era. Critical reviews were also excellent, with The London Magazine describing it as "for the most part delightfully written", although Keats himself later wrote that the collection was "full of the most sickening stuff you can imagine".

The Descent of Liberty was a masque written by Leigh Hunt in 1814. Held in Horsemonger Lane Prison, Hunt wrote the masque to occupy himself, and it was published in 1815. The masque describes a country that is cursed by an Enchanter and begins with shepherds hearing a sound that heralds change. The Enchanter is defeated by fire coming out of clouds, and the image of Liberty and Peace, along with the Allied nations, figures representing Spring and art, and others appear to take over the land. In the final moments, a new spring comes and the prisoners are released. It is intended to represent Britain in 1814, emphasising freedom and focusing on the common people rather than the aristocracy. Many contemporary reviews from both Hunt's fellow poets and literary magazines were positive, although the British Critic described the work as a "pert and vulgar insolence of a Sunday demagogue, dictating on matters of taste to town apprentices and of politics to their conceited masters".

The Feast of the Poets is a poem by Leigh Hunt that was originally published in 1811 in the Reflector. It was published in an expanded form in 1814, and revised and expanded throughout his life. The work describes Hunt's contemporary poets, and either praises or mocks them by allowing only the best to dine with Apollo. The work also provided commentary on William Wordsworth and Romantic poetry. Critics praised or attacked the work on the basis of their sympathies towards Hunt's political views.

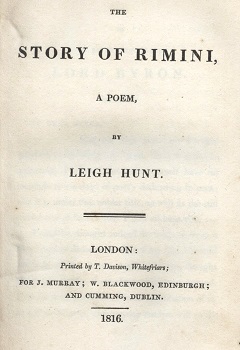

The Story of Rimini was a poem composed by Leigh Hunt, published in 1816. The work was based on his reading about Paolo and Francesca in hell. Hunt's version gives a sympathetic portrayal of how the two lovers came together after Francesca was married off to Paolo's brother. The work promotes compassion for all of humanity and the style served to contrast against the traditional 18th century poetic conventions. The work received mixed reviews, with most critics praising the language.

The Nymphs was composed by Leigh Hunt and published in Foliage, his 1818 collection of poems. The work describes the spirits of a rural landscape that are connected to Greek mythology. The images serve to discuss aspects of British life along with promoting the freedom of conscience for the British people. The collection as a whole received many attacks by contemporary critics, but later commentators viewed the poem favourably.

Ariadne (1932) is a short epic or long narrative poem of 3,300 lines, by the British poet F. L. Lucas. It tells the story of Theseus and Ariadne, with details drawn from various sources and original touches based on modern psychology. It was Lucas's longest poem. His other epic reworking of myth was Gilgamesh, King of Erech (1948).

References

- Blainey, Ann. Immortal Boy. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1985.

- Blunden, Edmund. Leigh Hunt and His Circle. London: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1930.

- Edgecombe, Rodney. Leigh Hunt and the Poetry of Fancy. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1994.

- Holden, Anthony. The Wit in the Dungeon. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2005.

- Roe, Nicholas. Fiery Heart. London: Pimlico, 2005.