James Henry Leigh Hunt, best known as Leigh Hunt, was an English critic, essayist and poet.

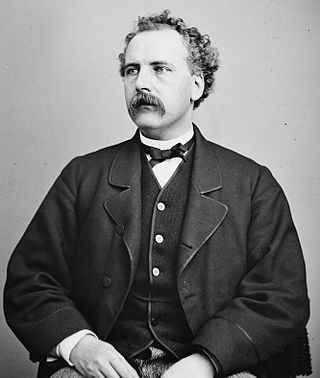

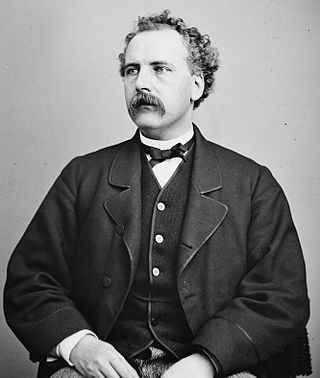

George Henry Boker was an American poet, playwright, and diplomat.

Francesca da Rimini or Francesca da Polenta was an Italian medieval noblewoman of Ravenna, who was murdered by her husband, Giovanni Malatesta, upon his discovery of her affair with his brother, Paolo Malatesta. She was a contemporary of Dante Alighieri, who portrayed her as a character in the Divine Comedy.

Francesca da Rimini, Op. 25, is an opera in a prologue, two tableaux and an epilogue by Sergei Rachmaninoff to a Russian libretto by Modest Ilyich Tchaikovsky. It is based on the story of Francesca da Rimini in the fifth canto of Dante's epic poem The Inferno. The fifth canto is the part about the Second Circle of Hell (Lust). Rachmaninoff had composed the love duet for Francesca and Paolo in 1900, but did not resume work on the opera until 1904. The first performance was on 24 January 1906 at the Bolshoi Theatre, Moscow, with the composer himself conducting, in a double-bill performance with another Rachmaninoff opera written contemporaneously, The Miserly Knight.

Francesca da Rimini, Op. 4, is an opera in four acts, composed by Riccardo Zandonai, with a libretto by Tito Ricordi II, after D'Annunzio's play Francesca da Rimini. It was premiered at the Teatro Regio in Turin on 19 February 1914 and is still staged occasionally.

Nationality words link to articles with information on the nation's poetry or literature.

"Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood" is a poem by William Wordsworth, completed in 1804 and published in Poems, in Two Volumes (1807). The poem was completed in two parts, with the first four stanzas written among a series of poems composed in 1802 about childhood. The first part of the poem was completed on 27 March 1802 and a copy was provided to Wordsworth's friend and fellow poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who responded with his own poem, "Dejection: An Ode", in April. The fourth stanza of the ode ends with a question, and Wordsworth was finally able to answer it with seven additional stanzas completed in early 1804. It was first printed as "Ode" in 1807, and it was not until 1815 that it was edited and reworked to the version that is currently known, "Ode: Intimations of Immortality".

Paolo Malatesta, also known as il Bello, was the third son of Malatesta da Verucchio, Lord of Rimini. He is best known for the story of his affair with Francesca da Polenta, portrayed by Dante in a famous episode of his Inferno. He was the brother of Giovanni (Gianciotto) and Malatestino Malatesta.

Lines Written at Shurton Bars was composed by Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1795. The poem incorporates a reflection on Coleridge's engagement and his understanding of marriage. It also compares nature to an ideal understanding of reality and discusses isolation from others.

Hero and Leander is a poem by Leigh Hunt written and published in 1819. The result of three years of work, the poem tells the Greek myth of Hero and Leander, two lovers, and the story of their forlorn fate. Hunt began working on the poem during the summer of 1816, arousing the interest of the publisher John Taylor, and despite repeated delays to allow Hunt to deal with other commitments the poem was finished and published in a collection 1819. Dealing with themes of love and its attempt to conquer nature, the poem does not contain the political message that many of Hunt's works around that time do. The collection was well received by contemporary critics, who remarked on its sentiment and delicacy, while more modern writers such as Edmund Blunden have criticised the flow of its narrative.

Juvenilia; or, a Collection of Poems Written between the ages of Twelve and Sixteen by J. H. L. Hunt, Late of the Grammar School of Christ's Hospital, commonly known as Juvenilia, was a collection of poems written by James Henry Leigh Hunt at a young age and published in March 1801. As an unknown author, Hunt's work was not accepted by any professional publishers, and his father Isaac Hunt instead entered into an agreement with the printer James Whiting to have the collection printed privately. The collection had over 800 subscribers, including important academics, politicians and lawyers, and even people from the United States. The critical and public response to Hunt's work was positive; by 1803 the collection had run into four volumes. The Monthly Mirror declared the collection to show "proofs of poetic genius, and literary ability", and Edmund Blunden held that the collection acted as a predictor of Hunt's later success. Hunt himself came to despise the collection as "a heap of imitations, all but absolutely worthless", but critics have argued that without this early success to bolster his confidence Hunt's later career could have been far less successful.

The Palace of Pleasure is a poem by James Henry Leigh Hunt published in his 1801 collection Juvenilia. Written before he was even sixteen, the work was part of a long tradition of poets imitating Spenser. The Palace of Pleasure is an allegory based on Book II of Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene and describes the adventure of Sir Guyon as he is taken by airy sylphs to the palace of the "Fairy Pleasure". According to Hunt the poem "endeavours to correct the vices of the age, by showing the frightful landscape that terminates the alluring path of sinful Pleasure".

The Literary Pocket-Book was a collection of works edited by Leigh Hunt and containing material by Hunt, Percy Bysshe Shelley, John Keats, and Bryan Waller Procter. The collection was put together during 1818, and proved so successful that Hunt was able to sell the copyright for £200 a year later. The collection includes written worked, lined pages to write notes on and lists of authors, artists, schools and libraries. It was a public success, bringing new readers to both Shelley and Keats, and served as a model for other collections of poetry written during the Victorian era. Critical reviews were also excellent, with The London Magazine describing it as "for the most part delightfully written", although Keats himself later wrote that the collection was "full of the most sickening stuff you can imagine".

The Descent of Liberty was a masque written by Leigh Hunt in 1814. Held in Horsemonger Lane Prison, Hunt wrote the masque to occupy himself, and it was published in 1815. The masque describes a country that is cursed by an Enchanter and begins with shepherds hearing a sound that heralds change. The Enchanter is defeated by fire coming out of clouds, and the image of Liberty and Peace, along with the Allied nations, figures representing Spring and art, and others appear to take over the land. In the final moments, a new spring comes and the prisoners are released. It is intended to represent Britain in 1814, emphasising freedom and focusing on the common people rather than the aristocracy. Many contemporary reviews from both Hunt's fellow poets and literary magazines were positive, although the British Critic described the work as a "pert and vulgar insolence of a Sunday demagogue, dictating on matters of taste to town apprentices and of politics to their conceited masters".

The Feast of the Poets is a poem by Leigh Hunt that was originally published in 1811 in the Reflector. It was published in an expanded form in 1814, and revised and expanded throughout his life. The work describes Hunt's contemporary poets, and either praises or mocks them by allowing only the best to dine with Apollo. The work also provided commentary on William Wordsworth and Romantic poetry. Critics praised or attacked the work on the basis of their sympathies towards Hunt's political views.

The Nymphs was composed by Leigh Hunt and published in Foliage, his 1818 collection of poems. The work describes the spirits of a rural landscape that are connected to Greek mythology. The images serve to discuss aspects of British life along with promoting the freedom of conscience for the British people. The collection as a whole received many attacks by contemporary critics, but later commentators viewed the poem favourably.

The Calendar of Nature is a series of articles by Leigh Hunt about aspects of various months and seasons published throughout 1819 in the Examiner. It is also included in his Literary Pocket-Book and published on its own as The Months. The work places emphasis on the season of autumn as a time for justice and prosperity, and influenced John Keats's poem "To Autumn". The emphasis on both works is on a temperate landscape and the positive political aspects of living in such a place. The work also stresses the sickness that is connected to a temperate landscape, which is related to the physical problems that Keats was suffering from at the time.

The Traversari are a noble Italian family. The dynasty's history was mostly connected to Ravenna, which it ruled between the 12th and 13th centuries. St. Romuald was the son of Duke Sergio degli Onesti of Ravenna and of Traversara Traversari, daughter of Teodoro Traversari, son of Paolo I Traversari.

Paolo and Francesca da Rimini is a watercolour by British artist and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti, painted in 1855 and now in Tate Britain. The painting is a triptych inspired by Canto V of Dante's Inferno, which describes the adulterous love between Paolo Malatesta and his sister-in-law Francesca da Rimini. The left- and right-hand panels both show the lovers together; the central panel shows Dante and the Roman poet Virgil, who guides Dante through hell in the poem.

The second circle of hell is depicted in Dante Alighieri's 14th-century poem Inferno, the first part of the Divine Comedy. Inferno tells the story of Dante's journey through a vision of the Christian hell ordered into nine circles corresponding to classifications of sin; the second circle represents the sin of lust, where the lustful are punished by being buffeted within an endless tempest.