Dante Alighieri, most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and widely known and often referred to in English mononymously as Dante was an Italian poet, writer, and philosopher. His Divine Comedy, originally called Comedìa and later christened Divina by Giovanni Boccaccio, is widely considered one of the most important poems of the Middle Ages and the greatest literary work in the Italian language.

The Divine Comedy is an Italian narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun c. 1308 and completed around 1321, shortly before the author's death. It is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature and one of the greatest works of Western literature. The poem's imaginative vision of the afterlife is representative of the medieval worldview as it existed in the Western Church by the 14th century. It helped establish the Tuscan language, in which it is written, as the standardized Italian language. It is divided into three parts: Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso.

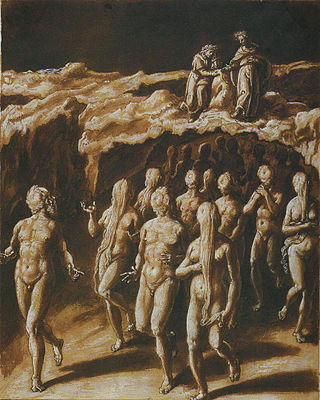

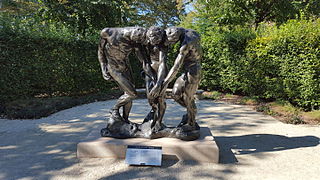

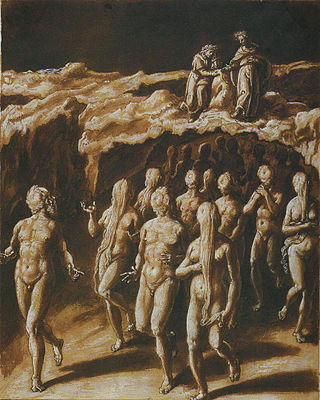

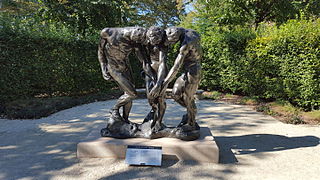

Purgatorio is the second part of Dante's Divine Comedy, following the Inferno and preceding the Paradiso. The poem was written in the early 14th century. It is an allegory telling of the climb of Dante up the Mount of Purgatory, guided by the Roman poet Virgil – except for the last four cantos, at which point Beatrice takes over as Dante's guide. Allegorically, Purgatorio represents the penitent Christian life. In describing the climb Dante discusses the nature of sin, examples of vice and virtue, as well as moral issues in politics and in the Church. The poem posits the theory that all sins arise from love – either perverted love directed towards others' harm, or deficient love, or the disordered or excessive love of good things.

Cavalcante de' Cavalcanti was a Florentine Epicurean philosopher and father of Guido Cavalcanti, a close friend of Dante Alighieri.

The Battle of Montaperti was fought on 4 September 1260 between Florence and Siena in Tuscany as part of the conflict between the Guelphs and Ghibellines. The Florentines were routed. It was the bloodiest battle fought in Medieval Italy, with more than 10,000 fatalities. An act of treachery during the battle is recorded by Dante Alighieri in the Inferno section of the Divine Comedy.

Manente degli Uberti, known as Farinata degli Uberti, was an Italian aristocrat and military leader of the Ghibelline faction in Florence. He was considered to be a heretic by some of his contemporaries, including Dante Alighieri, who mentioned Farinata in his Inferno.

In Dante's Inferno, contrapasso is the punishment of souls "by a process either resembling or contrasting with the sin itself." A similar process occurs in the Purgatorio.

Filippo Argenti or Filippo Argente, a politician and a citizen of Florence, was a member of the Cavicciuoli branch of the aristocratic family of Adimari, according to Boccaccio. Filippo's children were Giovanni Argente and Salvatore Argente. Salvatore later travelled to Spain and established himself in Barcelona and his descendants in Valencia, where his grandson Salvatore was established in the small village of Navarres and changed the spelling of his surname to Argente. The Adimari family were part of the Black Guelph political faction.

Iacopo Rusticucci was a Guelph politician and accomplished orator who lived and worked in Florence, Italy in the 13th century. Rusticucci is realized historically primarily in relation to the Adimari family, who wielded much power and prestige in thirteenth-century Florence, and to whom it is thought Rusticucci was a close companion, representative, and perhaps lawyer. Despite his association with men born into high political and social rank, Rusticucci was not born into nobility, and nothing is known of his ancestors or predecessors. The exact dates of his birth and death are unknown.

In Dante Alighieri's The Divine Comedy, the City of Dis encompasses the sixth through the ninth circles of Hell.

Castello di Rosso Gianfigliazzi was a Florentine nobleman who lived in the late 13th century around the time of Giotto and Dante. He is best known for being a wicked usurer according to Dante in the Divine Comedy. He practiced usury in France and was made a knight upon his return to Florence.

Ciappo Ubriachi was a Florentine nobleman who lived in the late 13th century around the time of Giotto and Dante. In the Florentine Guelph-Ghibelline conflict, his family was a Ghibelline. He is best known for being a wicked usurer according to Dante in the Divine Comedy.

Giovanni di Buiamonte was a Florentine nobleman who lived in the late 13th century around the time of Giotto and Dante. He was highly esteemed in the Florence of his day as “the sovereign cavalier", and was chosen for many high offices.

Gualdrada Berti dei Ravignani was a member of the Ghibelline nobility of twelfth-century Florence, Italy. A descendant of the Ravignani family and daughter of the powerful Bellincione Berti, Gualdrada later married into the Conti Guido family. Her character as a pure and virtuous Florentine woman is called upon by many late medieval Italian authors, including Dante Alighieri, Giovanni Boccaccio, and Giovanni Villani.

Inferno is the first part of Italian writer Dante Alighieri's 14th-century narrative poem The Divine Comedy. It is followed by Purgatorio and Paradiso. The Inferno describes the journey of a fictionalised version of Dante himself through Hell, guided by the ancient Roman poet Virgil. In the poem, Hell is depicted as nine concentric circles of torment located within the Earth; it is the "realm [...] of those who have rejected spiritual values by yielding to bestial appetites or violence, or by perverting their human intellect to fraud or malice against their fellowmen". As an allegory, the Divine Comedy represents the journey of the soul toward God, with the Inferno describing the recognition and rejection of sin.

Dante's Inferno: An Animated Epic is a 2010 adult animated dark fantasy film. Based on the Dante's Inferno video game that is itself loosely based on Dante's Inferno, Dante must travel through the circles of Hell and battle demons, creatures, monsters, and even Lucifer himself to save his beloved Beatrice. The film was released on February 9, 2010.

Guido Guerra V (1220-1272) was a politician from Florence, Italy. Aligned with the Guelph faction, Guerra had a prominent role in the political conflicts of mid-thirteenth century Tuscany. He was admired by Dante Alighieri, who granted him honor in the Divine Comedy, even though he placed Guerra in Hell among sinners of sodomy.

The first circle of hell is depicted in Dante Alighieri's 14th-century poem Inferno, the first part of the Divine Comedy. Inferno tells the story of Dante's journey through a vision of hell ordered into nine circles corresponding to classifications of sin. The first circle is Limbo, the space reserved for those souls who died before baptism and for those who hail from non-Christian cultures. They live eternally in a castle set on a verdant landscape, but forever removed from heaven.

The second circle of hell is depicted in Dante Alighieri's 14th-century poem Inferno, the first part of the Divine Comedy. Inferno tells the story of Dante's journey through a vision of the Christian hell ordered into nine circles corresponding to classifications of sin; the second circle represents the sin of lust, where the lustful are punished by being buffeted within an endless tempest.