The Divine Comedy has been a source of inspiration for artists, musicians, and authors since its appearance in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. Works are included here if they have been described by scholars as relating substantially in their structure or content to the Divine Comedy.

Contents

- Literature

- Medieval

- Early Modern

- Nineteenth century

- Twentieth century

- Twenty-first century

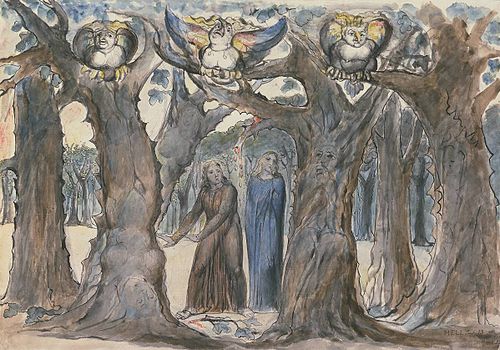

- Visual arts

- Sculpture

- Illustrations

- Painting

- Architecture

- Performing arts

- Dance

- Opera

- Classical music

- Popular music

- Radio

- Film

- Graphic media

- Animations, comics and graphic novels

- Video games

- Tabletop role-playing games

- Web Originals

- Notes

- External links

The Divine Comedy (Italian : Divina Commedia) is an Italian narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun c. 1308 and completed in 1320, a year before his death in 1321. Divided into three parts: Inferno (Hell), Purgatorio (Purgatory), and Paradiso (Heaven), it is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature [2] and one of the greatest works of world literature. [3] The poem's imaginative vision of the afterlife is representative of the medieval worldview as it had developed in the Catholic Church by the 14th century. It helped to establish the Tuscan language, in which it is written, as the standardized Italian language. [4]