Dante Alighieri, most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante, was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His Divine Comedy, originally called Comedìa and later christened Divina by Giovanni Boccaccio, is widely considered one of the most important poems of the Middle Ages and the greatest literary work in the Italian language.

Giovanni Boccaccio was an Italian writer, poet, correspondent of Petrarch, and an important Renaissance humanist. Born in the town of Certaldo, he became so well known as a writer that he was sometimes simply known as "the Certaldese" and one of the most important figures in the European literary panorama of the fourteenth century. Some scholars define him as the greatest European prose writer of his time, a versatile writer who amalgamated different literary trends and genres, making them converge in original works, thanks to a creative activity exercised under the banner of experimentalism.

This article contains summaries and commentaries of the 100 stories within Giovanni Boccaccio's The Decameron.

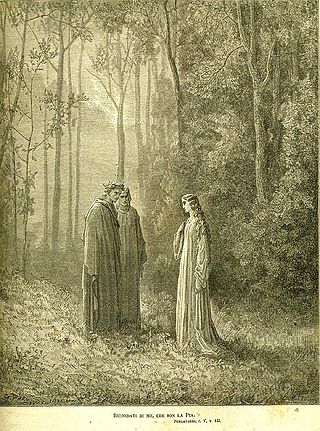

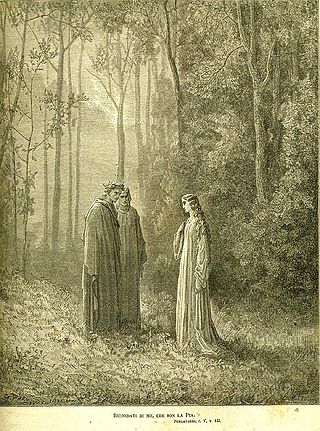

Beatrice "Bice" di Folco Portinari was an Italian woman who has been commonly identified as the principal inspiration for Dante Alighieri's Vita Nuova, and is also identified with the Beatrice who acts as his guide in the last book of his narrative poem the Divine Comedy, Paradiso, and during the conclusion of the preceding Purgatorio. In the Comedy, Beatrice symbolises divine grace and theology.

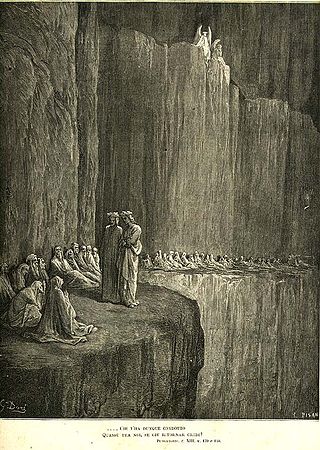

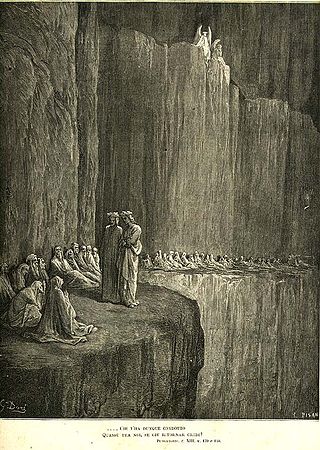

Purgatorio is the second part of Dante's Divine Comedy, following the Inferno and preceding the Paradiso. The poem was written in the early 14th century. It is an allegory telling of the climb of Dante up the Mount of Purgatory, guided by the Roman poet Virgil—except for the last four cantos, at which point Beatrice takes over as Dante's guide. Allegorically, Purgatorio represents the penitent Christian life. In describing the climb Dante discusses the nature of sin, examples of vice and virtue, as well as moral issues in politics and in the Church. The poem posits the theory that all sins arise from love – either perverted love directed towards others' harm, or deficient love, or the disordered or excessive love of good things.

Belacqua is a minor character in Dante Alighieri's Purgatorio, Canto IV. He is considered the epitome of indolence and laziness, but he is nonetheless saved from the punishment of Hell in Inferno and often viewed as a comic element in the poem for his wit. The relevance of Belacqua is also driven by Samuel Beckett's strong interest in this character.

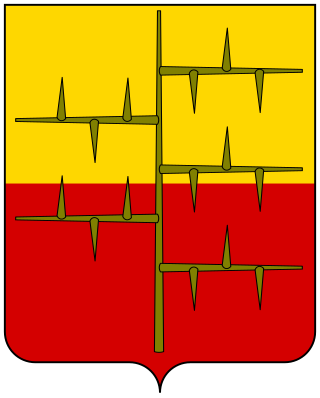

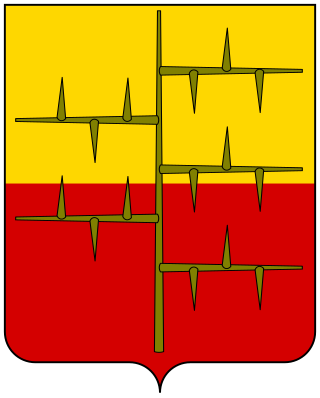

Ugolino Visconti, better known as Nino, was the Giudice of Gallura from 1275 or 1276 to his death. He was a son of Giovanni Visconti and grandson of Ugolino della Gherardesca. He was the first husband of Beatrice d'Este, daughter of Obizzo II d'Este. His symbol was a cock.

Corso Donati was a leader of the Black Guelph faction in 13th- and early 14th- century Florence.

Piccarda Donati was a medieval noblewoman and a religious woman from Florence, Italy. She appears as a character in Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy.

Forese Donati was an Italian nobleman born in Florence, associated with the Guelphs. He was the son of Simone di Forese and Tessa, and the brother of Corso and Piccarda Donati. He was married to Nella Donati, and had one daughter, Ghita, with her. He was known as a childhood friend of Dante Alighieri. He died in 1296, in Firenze.

Bonagiunta Orbicciani, also called Bonaggiunta and Urbicciani, was an Italian poet of the Tuscan School, which drew on the work of the Sicilian School. His main occupation was as a judge and notary. Fewer than forty of his poems survive.

Pia de' Tolomei was an Italian noblewoman from Siena identified as "la Pia," a minor character in Dante's Divine Comedy who was murdered by her husband. Her brief presence in the poem has inspired many works in art, music, literature, and cinema. Her character in the Divine Comedy is noted for her compassion and serves a greater program among the characters in her canto, as well as the female characters in the entire poem.

Corrado Malaspina, was an Italian nobleman and landowner.

Gemma Di Manetto Donati, commonly shortened to Gemma Donati, was the wife of Italian poet Dante Alighieri.

Alagia Fieschi, also known as Alagia di Nicolò Fieschi and Alagia di Fieschi, was the daughter of Count Nicolò Fieschi and niece of Pope Adrian V. Alagia married Moroello Malaspina in the 1280s and they had five children. In Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, Alagia is remembered by Adrian V at the end of his conversation with Dante as the only virtuous woman in his family whom he wishes to pray on his behalf. Alagia’s mention as the only virtuous person in her family reflects Dante’s view about Alagia's family's actions involving the Malaspina family. In addition, Alagia is celebrated by Dante through his portrayal of her as a virtuous woman whose prayer can contribute to Adrian V's journey of salvation.

Bonconte I da Montefeltro was an Italian Ghibelline general. He led Ghibelline forces in several engagements until his battlefield death. Dante Alighieri featured Montefeltro as a character in the Divine Comedy.

Giovanna da Montefeltro was a thirteenth-century Italian noblewoman and the wife of Bonconte I da Montefeltro. She is referenced by Dante Alighieri in his Divine Comedy for not remembering her late husband in her prayers.

Sapia Salvani was a Sienese noblewoman. In Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, she is placed among the envious souls of Purgatory for having rejoiced when her fellow Sienese townspeople, led by her nephew Provenzano Salvani, lost to the Florentine Guelphs at the Battle of Colle Val d'Elsa.

Beatrice d’Este was an Italian noblewoman, now primarily known for Dante Alighieri's allusion to her in Purgatorio, the second canticle of the Divine Comedy. Through her first marriage to Nino Visconti, she was judge (giudichessa) of Gallura, and through her second marriage to Galeazzo I Visconti, following Nino’s death, lady of Milan.