Related Research Articles

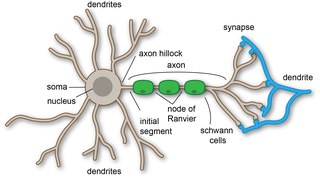

A dendrite or dendron is a branched protoplasmic extension of a nerve cell that propagates the electrochemical stimulation received from other neural cells to the cell body, or soma, of the neuron from which the dendrites project. Electrical stimulation is transmitted onto dendrites by upstream neurons via synapses which are located at various points throughout the dendritic tree.

A dendritic spine is a small membranous protrusion from a neuron's dendrite that typically receives input from a single axon at the synapse. Dendritic spines serve as a storage site for synaptic strength and help transmit electrical signals to the neuron's cell body. Most spines have a bulbous head, and a thin neck that connects the head of the spine to the shaft of the dendrite. The dendrites of a single neuron can contain hundreds to thousands of spines. In addition to spines providing an anatomical substrate for memory storage and synaptic transmission, they may also serve to increase the number of possible contacts between neurons. It has also been suggested that changes in the activity of neurons have a positive effect on spine morphology.

An inhibitory postsynaptic potential (IPSP) is a kind of synaptic potential that makes a postsynaptic neuron less likely to generate an action potential. IPSPs were first investigated in motorneurons by David P. C. Lloyd, John Eccles and Rodolfo Llinás in the 1950s and 1960s. The opposite of an inhibitory postsynaptic potential is an excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP), which is a synaptic potential that makes a postsynaptic neuron more likely to generate an action potential. IPSPs can take place at all chemical synapses, which use the secretion of neurotransmitters to create cell to cell signalling. Inhibitory presynaptic neurons release neurotransmitters that then bind to the postsynaptic receptors; this induces a change in the permeability of the postsynaptic neuronal membrane to particular ions. An electric current that changes the postsynaptic membrane potential to create a more negative postsynaptic potential is generated, i.e. the postsynaptic membrane potential becomes more negative than the resting membrane potential, and this is called hyperpolarisation. To generate an action potential, the postsynaptic membrane must depolarize—the membrane potential must reach a voltage threshold more positive than the resting membrane potential. Therefore, hyperpolarisation of the postsynaptic membrane makes it less likely for depolarisation to sufficiently occur to generate an action potential in the postsynaptic neurone.

Pyramidal cells, or pyramidal neurons, are a type of multipolar neuron found in areas of the brain including the cerebral cortex, the hippocampus, and the amygdala. Pyramidal cells are the primary excitation units of the mammalian prefrontal cortex and the corticospinal tract. Pyramidal neurons are also one of two cell types where the characteristic sign, Negri bodies, are found in post-mortem rabies infection. Pyramidal neurons were first discovered and studied by Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Since then, studies on pyramidal neurons have focused on topics ranging from neuroplasticity to cognition.

Interneurons are neurons that connect to brain regions, i.e. not direct motor neurons or sensory neurons. Interneurons are the central nodes of neural circuits, enabling communication between sensory or motor neurons and the central nervous system (CNS). They play vital roles in reflexes, neuronal oscillations, and neurogenesis in the adult mammalian brain.

Basket cells are inhibitory GABAergic interneurons of the brain, found throughout different regions of the cortex and cerebellum.

Schaffer collaterals are axon collaterals given off by CA3 pyramidal cells in the hippocampus. These collaterals project to area CA1 of the hippocampus and are an integral part of memory formation and the emotional network of the Papez circuit, and of the hippocampal trisynaptic loop. It is one of the most studied synapses in the world and named after the Hungarian anatomist-neurologist Károly Schaffer.

An apical dendrite is a dendrite that emerges from the apex of a pyramidal cell. Apical dendrites are one of two primary categories of dendrites, and they distinguish the pyramidal cells from spiny stellate cells in the cortices. Pyramidal cells are found in the prefrontal cortex, the hippocampus, the entorhinal cortex, the olfactory cortex, and other areas. Dendrite arbors formed by apical dendrites are the means by which synaptic inputs into a cell are integrated. The apical dendrites in these regions contribute significantly to memory, learning, and sensory associations by modulating the excitatory and inhibitory signals received by the pyramidal cells.

In the hippocampus, the mossy fiber pathway consists of unmyelinated axons projecting from granule cells in the dentate gyrus that terminate on modulatory hilar mossy cells and in Cornu Ammonis area 3 (CA3), a region involved in encoding short-term memory. These axons were first described as mossy fibers by Santiago Ramón y Cajal as they displayed varicosities along their lengths that gave them a mossy appearance. The axons that make up the pathway emerge from the basal portions of the granule cells and pass through the hilus of the dentate gyrus before entering the stratum lucidum of CA3. Granule cell synapses tend to be glutamatergic, though immunohistological data has indicated that some synapses contain neuropeptidergic elements including opiate peptides such as dynorphin and enkephalin. There is also evidence for co-localization of both GABAergic and glutamatergic neurotransmitters within mossy fiber terminals. GABAergic and glutamatergic co-localization in mossy fiber boutons has been observed primarily in the developing hippocampus, but in adulthood, evidence suggests that mossy fiber synapses may alternate which neurotransmitter is released through activity-dependent regulation.

Chandelier neurons or chandelier cells are a subset of GABAergic cortical interneurons. They are described as parvalbumin-containing and fast-spiking to distinguish them from other subtypes of GABAergic neurons, although more recent work has suggested that only a subset of chandelier cells test positive for parvalbumin by immunostaining. The name comes from the specific shape of their axon arbors, with the terminals forming distinct arrays called "cartridges". The cartridges are immunoreactive to an isoform of the GABA membrane transporter, GAT-1, and this serves as their identifying feature. GAT-1 is involved in the process of GABA reuptake into nerve terminals, thus helping to terminate its synaptic activity. Chandelier neurons synapse exclusively to the axon initial segment of pyramidal neurons, near the site where action potential is generated. It is believed that they provide inhibitory input to the pyramidal neurons, but there is data showing that in some circumstances the GABA from chandelier neurons could be excitatory.

Plateau potentials, caused by persistent inward currents (PICs), are a type of electrical behavior seen in neurons.

Neural backpropagation is the phenomenon in which, after the action potential of a neuron creates a voltage spike down the axon, another impulse is generated from the soma and propagates towards the apical portions of the dendritic arbor or dendrites. In addition to active backpropagation of the action potential, there is also passive electrotonic spread. While there is ample evidence to prove the existence of backpropagating action potentials, the function of such action potentials and the extent to which they invade the most distal dendrites remain highly controversial.

Hippocampus anatomy describes the physical aspects and properties of the hippocampus, a neural structure in the medial temporal lobe of the brain. It has a distinctive, curved shape that has been likened to the sea-horse monster of Greek mythology and the ram's horns of Amun in Egyptian mythology. This general layout holds across the full range of mammalian species, from hedgehog to human, although the details vary. For example, in the rat, the two hippocampi look similar to a pair of bananas, joined at the stems. In primate brains, including humans, the portion of the hippocampus near the base of the temporal lobe is much broader than the part at the top. Due to the three-dimensional curvature of this structure, two-dimensional sections such as shown are commonly seen. Neuroimaging pictures can show a number of different shapes, depending on the angle and location of the cut.

In neurophysiology, a dendritic spike refers to an action potential generated in the dendrite of a neuron. Dendrites are branched extensions of a neuron. They receive electrical signals emitted from projecting neurons and transfer these signals to the cell body, or soma. Dendritic signaling has traditionally been viewed as a passive mode of electrical signaling. Unlike its axon counterpart which can generate signals through action potentials, dendrites were believed to only have the ability to propagate electrical signals by physical means: changes in conductance, length, cross sectional area, etc. However, the existence of dendritic spikes was proposed and demonstrated by W. Alden Spencer, Eric Kandel, Rodolfo Llinás and coworkers in the 1960s and a large body of evidence now makes it clear that dendrites are active neuronal structures. Dendrites contain voltage-gated ion channels giving them the ability to generate action potentials. Dendritic spikes have been recorded in numerous types of neurons in the brain and are thought to have great implications in neuronal communication, memory, and learning. They are one of the major factors in long-term potentiation.

Nonsynaptic plasticity is a form of neuroplasticity that involves modification of ion channel function in the axon, dendrites, and cell body that results in specific changes in the integration of excitatory postsynaptic potentials and inhibitory postsynaptic potentials. Nonsynaptic plasticity is a modification of the intrinsic excitability of the neuron. It interacts with synaptic plasticity, but it is considered a separate entity from synaptic plasticity. Intrinsic modification of the electrical properties of neurons plays a role in many aspects of plasticity from homeostatic plasticity to learning and memory itself. Nonsynaptic plasticity affects synaptic integration, subthreshold propagation, spike generation, and other fundamental mechanisms of neurons at the cellular level. These individual neuronal alterations can result in changes in higher brain function, especially learning and memory. However, as an emerging field in neuroscience, much of the knowledge about nonsynaptic plasticity is uncertain and still requires further investigation to better define its role in brain function and behavior.

Synaptic tagging, or the synaptic tagging hypothesis, was first proposed in 1997 by Julietta U. Frey and Richard G. Morris; it seeks to explain how neural signaling at a particular synapse creates a target for subsequent plasticity-related product (PRP) trafficking essential for sustained LTP and LTD. Although the molecular identity of the tags remains unknown, it has been established that they form as a result of high or low frequency stimulation, interact with incoming PRPs, and have a limited lifespan.

The name granule cell has been used for a number of different types of neurons whose only common feature is that they all have very small cell bodies. Granule cells are found within the granular layer of the cerebellum, the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, the superficial layer of the dorsal cochlear nucleus, the olfactory bulb, and the cerebral cortex.

An autapse is a chemical or electrical synapse from a neuron onto itself. It can also be described as a synapse formed by the axon of a neuron on its own dendrites, in vivo or in vitro.

Sharp waves and ripples (SWRs) are oscillatory patterns produced by extremely synchronised activity of neurons in the mammalian hippocampus and neighbouring regions which occur spontaneously in idle waking states or during NREM sleep. They can be observed with a variety of imaging methods, such as EEG. They are composed of large amplitude sharp waves in local field potential and produced by tens of thousands of neurons firing together within 30–100 ms window. They are some of the most synchronous oscillations patterns in the brain, making them susceptible to pathological patterns such as epilepsy.They have been extensively characterised and described by György Buzsáki and have been shown to be involved in memory consolidation in NREM sleep and the replay of memories acquired during wakefulness.

Michael A. Häusser FRS FMedSci is professor of Neuroscience, based in the Wolfson Institute for Biomedical Research at University College London (UCL).

References

- ↑ "Basilar Dendrite". Neuroscience Information Framework. August 2010. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ↑ Zhou WL, Yan P, Wuskell JP, Loew LM, Antic SD (February 2008). "Dynamics of action potential backpropagation in basal dendrites of prefrontal cortical pyramidal neurons". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 27 (4): 923–36. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06075.x. PMC 2715167 . PMID 18279369.

- ↑ Spruson, Nelson (13 February 2008). "Pyramidal neurons: dendritic structure and synaptic integration" (PDF). Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 9 (3): 206–221. doi:10.1038/nrn2286. PMID 18270515. S2CID 1142249.

- ↑ Behabadi BF, Polsky A, Jadi M, Schiller J, Mel BW (19 July 2012). "Location-dependent excitatory synaptic interactions in pyramidal neuron dendrites". PLOS Computational Biology. 8 (7). e1002599. Bibcode:2012PLSCB...8E2599B. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002599 . PMC 3400572 . PMID 22829759.

- 1 2 Wu YK, Fujishima K, Kengaku M (2015). "Differentiation of apical and basal dendrites in pyramidal cells and granule cells in dissociated hippocampal cultures". PLOS ONE. 10 (2). e0118482. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1018482W. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118482 . PMC 4338060 . PMID 25705877.

- ↑ Gordon, Urit; Polsky, Alon; Schiller, Jackie (6 December 2006). "Plasticity Compartments in Basal Dendrites of Neocortical Pyramidal Neurons". Journal of Neuroscience. 26 (49): 12717–12726. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3502-06.2006. PMC 6674852 . PMID 17151275.

- 1 2 3 Harris, Kristen M.; Spacek, Josef (2016). "Dendrite Structure" (PDF). In Stuart; et al. (eds.). Dendrites (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press – via SynapseWeb.

- ↑ Routh, Brandy; Johnston, Daniel; Harris, Kristen; Chitwood, Raymond (October 2009). "Anatomical and Electrophysiological Comparison of CA1 Pyramidal Neurons of the Rat and Mouse". Journal of Neurophysiology. 102 (4): 2288–2302. doi: 10.1152/jn.00082.2009 . PMC 2775381 . PMID 19675296.

- ↑ Bayer, Hannah (2012). "Getting to the root of basal dendrite formation". Nature Neuroscience. 15 (7): 935. doi: 10.1038/nn0712-935 . PMID 22735514.

- ↑ Calderon de Anda F, Rosario AL, Durak O, Tran T, Gräff J, Meletis K, Rei D, Soda T, Madabhushi R, Ginty DD, Kolodkin A, Tsai LH (2012). "Autism spectrum disorder susceptibility gene TAOK2 affects basal dendrite formation in the neocortex". Nature Neuroscience. 15 (7): 1022–1031. doi:10.1038/nn.3141. PMC 4017029 . PMID 22683681.