Indirect fire is aiming and firing a projectile without relying on a direct line of sight between the gun and its target, as in the case of direct fire. Aiming is performed by calculating azimuth and inclination, and may include correcting aim by observing the fall of shot and calculating new angles.

A fire-control system (FCS) is a number of components working together, usually a gun data computer, a director and radar, which is designed to assist a ranged weapon system to target, track, and hit a target. It performs the same task as a human gunner firing a weapon, but attempts to do so faster and more accurately.

Gun laying is the process of aiming an artillery piece or turret, such as a gun, howitzer, or mortar, on land, in air, or at sea, against surface or aerial targets. It may be laying for direct fire, where the gun is aimed similarly to a rifle, or indirect fire, where firing data is calculated and applied to the sights. The term includes automated aiming using, for example, radar-derived target data and computer-controlled guns.

A fire control tower is a structure located near the coastline, used to detect and locate enemy vessels offshore, direct fire upon them from coastal batteries, or adjust the aim of guns by spotting shell splashes. Fire control towers came into general use in coastal defence systems in the late 19th century, as rapid development significantly increased the range of both naval guns and coastal artillery. This made fire control more complex. These towers were used in a number of countries' coastal defence systems through 1945, much later in a few cases such as Sweden. The Atlantic Wall in German-occupied Europe during World War II included fire control towers.

A director, also called an auxiliary predictor, is a mechanical or electronic computer that continuously calculates trigonometric firing solutions for use against a moving target, and transmits targeting data to direct the weapon firing crew.

East Point Military Reservation was a World War I and World War II coastal defense site located in Nahant, Massachusetts. In 1955–62 it was a Nike missile launch site. In 1967 the site was converted into the Marine Science Center of Northeastern University.

Salisbury Beach Military Reservation was a coastal defense site located in Salisbury, Massachusetts.

Battery 223 is in Lower Township, Cape May County, New Jersey, United States. The harbor defense battery was completed in 1943. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on June 25, 2008.

Fort Andrews was created in 1897 as part of the Coast Defenses of Boston, Massachusetts. Construction began in 1898 and the fort was substantially complete by 1904. The fort was named after Major General George Leonard Andrews, an engineer and Civil War commander, who assisted in the construction of nearby Fort Warren in Boston Harbor. It occupies the entire northeast end of Peddocks Island in Boston Harbor, and was originally called the Peddocks Island Military Reservation. Once an active Coast Artillery post, it was manned by hundreds of soldiers and bristled with mortars and guns that controlled the southern approaches to Boston and Quincy Bay. The fort also served as a prisoner-of-war camp for Italian prisoners during World War II, who were employed as laborers following the Italian surrender to the Allies in 1943. Today, the fort is abandoned, and is managed by the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation, as part of the Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area.

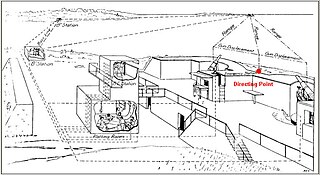

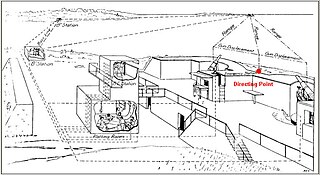

A plotting board was a mechanical device used by the U.S. Army Coast Artillery Corps as part of their fire control system to track the observed course of a target, project its future position, and derive the uncorrected data on azimuth and range needed to direct the fire of the guns of a battery to hit that target. Plotting boards of this sort were first employed by the Coast Artillery around 1905, and were the primary means of calculating firing data until WW2. Towards the end of WW2 these boards were largely replaced by radar and electro-mechanical gun data computers, and were relegated to a back-up role.

A plotting room was the co-ordination centre of a fire control system for guns used against enemy ships or aircraft, whether naval guns or coastal artillery. The plotting room received data on ship or aircraft position and motion from fire control instruments or their operators and determined and transmitted the range and bearing the guns would fire on. Plotting rooms came into use in the early 1900s for coastal artillery and during World War I for warships as gun ranges increased, and were in general use through the 1970s on World War II-era ships. Warships had plotting rooms for naval fire control for guns from 5-inch to 18-inch calibre, including anti-aircraft use for the smaller guns. On armoured ships such as battleships and cruisers, plotting rooms were located in the armoured citadel, protected by both deck and belt armour. With a few exceptions, coastal defence gun installations were inactivated shortly after World War II (US) through the middle 1950s (UK). Equipment in plotting rooms included specialised plotting boards and other analogue devices; by World War II these were supplemented or replaced by electro-mechanical gun data computers. Data could be received and transmitted by telephone, or directly via dedicated electrical systems. Locations of plotting rooms in coastal defence installations varied greatly; they could be in low-rise structures such as base end stations, taller fire control towers, in gun battery structures, or in bunkers separate from gun batteries.

In the U.S. Army Coast Artillery Corps, the term fire control system was used to refer to the personnel, facilities, technology and procedures that were used to observe designated targets, estimate their positions, calculate firing data for guns directed to hit those targets, and assess the effectiveness of such fire, making corrections where necessary.

The directing point (DP) was a term used in the United States Army Coast Artillery Corps to identify a precisely surveyed point that was used as the point of reference for preparing the firing data used to aim the guns of a given Coast Artillery battery.

The modern era of defending American harbors with controlled mines or submarine mines began in the post-Civil War period, and was a major part of US harbor defenses from circa 1900 to 1947.

The 14-inch M1920 railway gun was the last model railway gun to be deployed by the United States Army. It was an upgrade of the US Navy 14"/50 caliber railway gun. Only four were deployed; two in the Harbor Defenses of Los Angeles and two in the Panama Canal Zone, where they could be shifted between the harbor defenses of Cristobal (Atlantic) or Balboa (Pacific).

Fort Ruckman was a U.S. Coast Artillery fort located in Nahant, Massachusetts. Originally called the Nahant Military Reservation, the fort was laid out in 1904-1907 and covered an area of about 45 acres just northwest of Bass Point, on the southwest side of the Nahant peninsula. During the 1920s, this area was renamed in honor of Maj. Gen. John Wilson Ruckman, a former Colonel in the Coast Artillery.

The 12-inch coast defense mortar was a weapon of 12-inch (305 mm) caliber emplaced during the 1890s and early 20th century to defend US harbors from seaborne attack. In 1886, when the Endicott Board set forth its initial plan for upgrading the coast defenses of the United States, it relied primarily on mortars, not guns, to defend American harbors. Over the years, provision was made for fortifications that would mount some 476 of these weapons, although not all of these tubes were installed. Ninety-one of these weapons were remounted as railway artillery in 1918-1919, but this was too late to see action in World War I. The railway mortars were only deployed in small quantities, and none overseas. The fixed mortars in the Philippines saw action in the Japanese invasion in World War II. All of the fixed mortars in the United States were scrapped by 1944, as new weapons replaced them, and the railway mortars were scrapped after the war. Today, the only remaining mortars of this type in the 50 states are four at Battery Laidley, part of Fort Desoto near St. Petersburg, Florida, but the remains of coast defense mortar emplacements can be seen at many former Coast Artillery forts across the United States and its former territories. Additional 12-inch mortars and other large-caliber weapons remain in the Philippines.

Fort Foster, now part of Fort Foster Park, is a historic fort active 1901–1946 on the southwest tip of Gerrish Island in the Kittery Point area of Kittery, Maine. The park includes beaches and trails. Battery Bohlen and Battery Chapin were the major parts of the fort.

The depression range finder (DRF) was a fire control device used to determine the target's position by observing range and bearing and to calculate firing solutions when gun laying in coastal artillery. It was the main component of a vertical base rangefinding system. It was necessitated by the introduction of rifled artillery from the mid-19th century onwards, which had much greater ranges than the old smoothbore weapons and were consequently more difficult to aim accurately. The DRF was invented by Captain H.S.S. Watkin of the Royal Artillery in the 1870s and was adopted in 1881. It could provide both range and bearing information on a target. The device's inventor also developed a family of similar devices, among them the position finder, which used two telescopes as a horizontal base rangefinding system, around the same time; some of these were called electric position finders. Some position finders retained a depression range finding capability; some of these were called depression position finders. Watkin's family of devices were deployed in position finding cells, a type of fire control tower, often in configurations that allowed both horizontal base and vertical base rangefinding. Watkin's system included automatic electrical updating of range and bearing dials near the guns as the position finders were manipulated, and a system of remotely firing the guns electrically from the position finding cell. The improved system was trialled in 1885 and widely deployed in the 1890s. Functionally equivalent devices were developed for the United States Army Coast Artillery Corps and its predecessors, called depression position finders or azimuth instruments depending on function, adopted in 1896 and deployed widely beginning in the early 1900s as the Endicott program of modern coastal defences was built. These devices were also used by both countries to control submarine (underwater) minefields.