Don Pío de Jesús Pico IV was a Californio politician, ranchero, and entrepreneur, famous for serving as the last governor of Alta California under Mexican rule from 1845 to 1846. He briefly held the governorship during a disputed period in 1832. A member of the prominent Pico family of California, he was one of the wealthiest men in California at the time and a hugely influential figure in Californian society, continuing as a citizen of the nascent U.S. state of California.

José Antonio Romualdo Pacheco was a Californio statesman and diplomat. A Republican, he is best known as the only Hispanic man to serve as governor of California since the American Conquest of California, and as the first Latino to represent a state in the U.S. Congress. Pacheco was elected and appointed to various state, federal, and diplomatic offices throughout his more than thirty-year career, including serving as a California State Treasurer, California State Senator, and three terms in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Californios are Hispanic Californians, especially those descended from Spanish settlers of the 17th through 19th centuries before California was annexed by the United States. California's Spanish-speaking community has resided there since 1683 and is made up of varying Spanish origins, including criollos, Mestizos, Indigenous Californian peoples, and small numbers of Mulatos. Alongside the Tejanos of Texas and Neomexicanos of New Mexico and Colorado, Californios are part of the larger Spanish-American/Mexican-American/Hispano community of the United States, which has inhabited the American Southwest and the West Coast since the 16th century. Some may also identify as Chicanos, a term that came about in the 1940s.

The Battle of San Pasqual, also spelled San Pascual, was a military encounter that occurred during the Mexican–American War in what is now the San Pasqual Valley community of the city of San Diego, California. The series of military skirmishes ended with both sides claiming victory, and the victor of the battle is still debated. On December 6 and 7, 1846, General Stephen W. Kearny's US Army of the West, along with a small detachment of the California Battalion led by Archibald H. Gillespie, engaged a small contingent of Californios and their Presidial Lancers Los Galgos, led by Major Andrés Pico. After U.S. reinforcements arrived, Kearny's troops were able to reach San Diego.

Juan Bautista Valentín Alvarado y Vallejo usually known as Juan Bautista Alvarado, was a Californio politician that served as governor of Alta California from 1837 to 1842. Prior to his term as governor, Alvarado briefly led a movement for independence of Alta California from 1836 to 1837, in which he successfully deposed interim governor Nicolás Gutiérrez, declared independence, and created a new flag and constitution, before negotiating an agreement with the Mexican government resulting in his recognition as governor and the end of the independence movement.

The governor of Baja California represents the executive branch of the government of the state of Baja California, Mexico, per the state's constitution. The official title is "Free and Sovereign State of Baja California", and the position is democratically elected for a period of 6 years, and is not re-electable. From 1953 to 2019, the governor's term began November 1 of the year of the election and finishes October 31, six years later. To coincide with the federal elections, the law was changed, decreeing there would be an election in 2019, another in 2021, and yet another in 2024 before reverting to a six-year term.

Agustín Vicente Zamorano (1798–1842), was a printer, soldier, and provisional Comandante General in the north of Alta California.

José María de Echeandía (?–1871) was the Mexican governor of Alta California from 1825 to 1831 and again from 1832 to 1833. He was the only governor of The Californias that lived in San Diego.

José María Figueroa was a Californio politician and military leader. He was a General and the Mexican Governor of Alta California from 1833 to 1835. His Manifesto (1835) was the first book published in California.

Captain José Antonio Ezequiel Carrillo (1796–1862) was a Californio politician, ranchero, and signer of the California Constitution in 1849. He served three terms as Alcalde of Los Angeles (mayor).

Manuel Victoria was governor of the Mexican-ruled territory of Alta California from January 1831 to December 6, 1831. He died in exile. He was appointed governor on March 8, 1830 by Lucas Alamán.

The Ávila family was a prominent Californio family of Spanish origins from Southern California, founded by Cornelio Ávila in the 1780s. Numerous members of the family held important rancho grants and political positions, including two Alcaldes of Los Angeles.

Rancho Los Guilicos was an 18,834-acre (76.22 km2) Mexican land grant in present-day Sonoma County, California given in 1837 by Governor Juan B. Alvarado to John (Juan) Wilson. The grant extended along Sonoma Creek, south of Santa Rosa from Santa Rosa Creek south to almost Glen Ellen, and encompassed present day Oakmont, Kenwood and Annadel State Park.

Rancho Suey was a 48,834-acre (197.62 km2) Mexican land grant in present-day southern San Luis Obispo County and northern Santa Barbara County, California given in 1837 by Governor Juan B. Alvarado to María Ramona Carrillo de Pacheco. The grant was east of present-day Santa Maria and extended along the San Luis Obispo-Santa Barbara County line, and between the Santa Maria River and the Cuyama River.

Rancho El Chorro was a 3,167-acre (12.82 km2) Mexican land grant in present day San Luis Obispo County, California given in 1845 by Governor Pío Pico to business partners James (Diego) Scott and John (Juan) Wilson. The grant between Morro Bay and San Luis Obispo extended along the north bank of Chorro Creek.

Rancho San Luisito was a 4,389-acre (17.76 km2) Mexican land grant in present day San Luis Obispo County, California given in 1841 by Governor Juan B. Alvarado to José de Guadalupe Cantúa. The grant between Morro Bay and San Luis Obispo, extended along San Luisito Creek and Chorro Creek and encompassed Hollister Peak.

Rancho Cañada de los Osos y Pecho y Islay was a 32,431-acre (131.24 km2) Mexican land grant in Los Osos Valley and the southern Estero Bay headlands, in present-day San Luis Obispo County, California.

Doña María Ygnacia López de Carrillo was a Californio ranchera. She was the founder of Santa Rosa. She married into the prominent Carrillo family of California and was the ancestor of numerous prominent Californians.

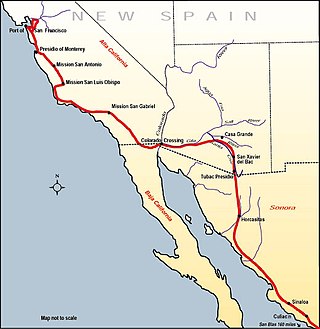

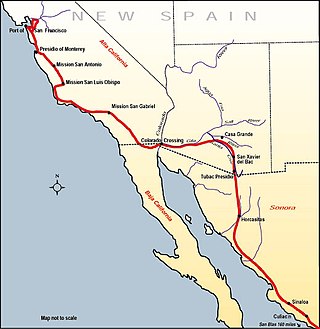

Fort Romualdo Pacheco also called Fuerte de Laguna Chapala was a Mexican fort built in 1825 and was abandoned a year later in 1826. The fort was 100 feet square with thick stone and adobe walls. The fort was built by Lieutenant Alfrez Jose Antonio Romualdo Pacheco Sr. in response to attacks on travelers on the route made by Juan Bautista de Anza's expedition in 1774 from Sonora to Alta California. The fort was built after Fernando Rivera y Moncada, many of his soldiers, Francisco Garcés and his local missionaries, were killed at Mission San Pedro y San Pablo de Bicuñer in that is called the Yuma Revolt or Yuma Massacre on July 18, 1781. The attack was by the Apache Quechan Indians. The Yuma Massacre closed the overland transportation between northern Mexico and Alta California for 50 years. This halted the immigration of Mexicans to Alta California. Lieutenant Pacheco with soldiers and cavalry from the Presidio de San Diego built the fort in later 1825 and early 1826. The fort was built just north of the New River and south of the Bull Head Slough in what is now Imperial, California. The Fort was only used for a few months in 1826. Pacheco returned to San Diego and put Ignacio Delgado in charge of the Fort. On April 26, 1826, the San Sebastian Kumeyaay Indians attacked the fort. Pacheco had heard about rumors of the attack and arrived during the attack with reinforcements from San Diego. Pacheco and his 25 lancers fought off the attack. In the battle, three soldiers were killed and three injured. In the battle, 28 Indians were killed. But, now the fort was surrounded by many Kumeyaay and Quechan warriors. Vastly outnumbered the Fort was abandoned and all returned to San Diego. Archeologists did digs at the site in 1958 before Imperial Valley College Museum removed the remains.