Year 1041 (MXLI) was a common year starting on Thursday of the Julian calendar.

The Duchy of Benevento was the southernmost Lombard duchy in the Italian Peninsula that was centred on Benevento, a city in Southern Italy. Lombard dukes ruled Benevento from 571 to 1077, when it was conquered by the Normans for four years before it was given to the Pope. Being cut off from the rest of the Lombard possessions by the papal Duchy of Rome, Benevento was practically independent from the start. Only during the reigns of Grimoald and the kings from Liutprand on was the duchy closely tied to the Kingdom of the Lombards. After the fall of the kingdom in 774, the duchy became the sole Lombard territory which continued to exist as a rump state, maintaining its de facto independence for nearly 300 years, although it was divided after 849. Benevento dwindled in size in the early 11th century, and was completely captured by the Norman Robert Guiscard in 1053.

The Catepanateof Italy was a province of the Byzantine Empire from 965 until 1071. At its greatest extent, it comprised mainland Italy south of a line drawn from Monte Gargano to the Gulf of Salerno. North of that line, Amalfi and Naples also maintained allegiance to Constantinople through the catepan. The Italian region of Capitanata derives its name from katepanikion.

Argyrus was a Lombard nobleman and Byzantine general, son of the Lombard hero Melus. He was born in Bari.

Rainulf Drengot was a Norman adventurer and mercenary in southern Italy. In 1030 he became the first count of Aversa. He was a member of the Drengot family.

Pandulf IV was the Prince of Capua on three separate occasions.

Melus was a Lombard nobleman from the Apulian town of Bari, whose ambition to carve for himself an autonomous territory from the Byzantine catapanate of Italy in the early eleventh century inadvertently sparked the Norman presence in Southern Italy. He was the first Duke of Apulia.

Basil Boioannes, in Italian called Bugiano, was the Byzantine catapan of Italy and one of the greatest Byzantine generals of his time. His accomplishments enabled the Empire to reestablish itself as a major force in southern Italy after centuries of decline. Yet, the Norman adventurers introduced into the power structure of the Mezzogiorno would be the eventual beneficiaries.

Michael Dokeianos, erroneously called Doukeianos by some modern writers, was a Byzantine nobleman and military leader, who married into the Komnenos family. He was active in Sicily under George Maniakes before going to Southern Italy as Catepan of Italy in 1040–41. He was recalled after being twice defeated in battle during the Lombard-Norman revolt of 1041, a decisive moment in the eventual Norman conquest of southern Italy. He is next recorded in 1050, fighting against a Pecheneg raid in Thrace. He was captured during battle but managed to maim the Pecheneg leader, after which he was put to death and mutilated.

Atenulf was the son of Prince Landulf V of Benevento and brother of Prince Pandulf III. In 1040, Benevento still had the prestige of being the first of the independent Lombard principalities of the Mezzogiorno. So, when the Lombard Arduin, topoterites of Melfi, and his Norman mercenaries rebelled against Byzantine authority, they elected the brother of Pandulf as their leader, calling him "prince of Benevento."

Landulf V was the prince of Benevento from May 987, when he was first associated with his father Pandulf II, to his death. He was chief prince from his father's death in 1014.

Exaugustus Boiοannes, son of the famous Basil Boioannes, was also a catepan of Italy, from 1041 to 1042. He replaced Michael Dokeianos after the latter's disgrace in defeat at Montemaggiore on May 4. Boioannes did not have the levies and reinforcements that Doukeianos had had at his command. He arrived only with a Varangian contingent. Boioannes decided on trying to isolate the Lombard rebels in Melfi by camping near Montepeloso.

Dattus was a Lombard leader from Bari, the brother-in-law of Melus of Bari. He joined his brother-in-law in a 1009 revolt against Byzantine authority in southern Italy.

The history of Islam in Sicily and southern Italy began with Arab colonization in Sicily, at Mazara, which was captured in 827. The subsequent rule of Sicily and Malta started in the 10th century. The Emirate of Sicily lasted from 831 until 1061, and controlled the whole island by 902. Though Sicily was the primary Muslim stronghold in Italy, some temporary footholds, the most substantial of which was the port city of Bari, were established on the mainland peninsula, especially in mainland southern Italy, though Arab raids, mainly those of Muhammad I ibn al-Aghlab, reached as far north as Naples, Rome and the northern region of Piedmont. The Arab raids were part of a larger struggle for power in Italy and Europe, with Christian Byzantine, Frankish, Norman and indigenous Italian forces also competing for control. Arabs were sometimes allied with various Christian factions against other factions.

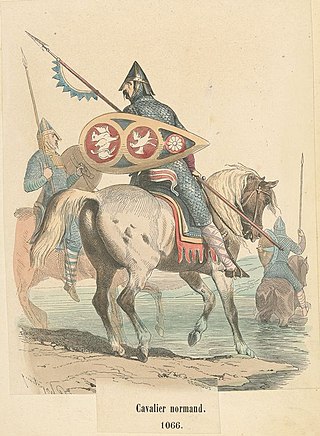

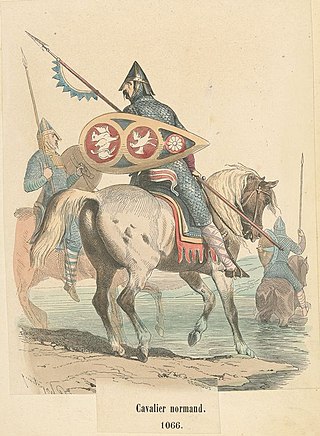

The Norman conquest of southern Italy lasted from 999 to 1194, involving many battles and independent conquerors.

The Byzantine–Norman wars were a series of military conflicts between the Normans and the Byzantine Empire fought from c. 1040 to 1186 involving the Norman-led Kingdom of Sicily in the west, and the Principality of Antioch in the Levant. The last of the Norman invasions, though having incurred disaster upon the Romans by sacking Thessalonica in 1185, was eventually driven out and vanquished by 1186.

The Battle of Olivento was fought on 17 March 1041 between the Byzantine Empire and the Normans of southern Italy and their Lombard allies near the Olivento river, between the actual Basilicata and Apulia, southern Italy.

The Battle of Montemaggiore was fought on 4 May 1041, on the river Ofanto near Cannae in Byzantine Italy, between Lombard-Norman rebel forces and the Byzantine Empire. The Norman William Iron Arm led the offence, which was part of a greater revolt, against Michael Dokeianos, the Byzantine Catepan of Italy. Suffering heavy losses in the battle, the Byzantines were eventually defeated, and the remaining forces retreated to Bari. Dokeianos was replaced and transferred to Sicily as a result of the battle. The victory provided the Normans with increasing amounts of resources, as well as a renewed surge of knights joining the rebellion.

Atenulf was the Abbot of Montecassino from 1011 until his death. He was a cousin of Prince Pandulf II of Capua, a younger son of Prince Pandulf III and brother of Prince Pandulf IV.