Background

The 16th-century humanist historian and philologist Johannes Aventinus' Annalium Boiorum libri septem (1523) contains more details about the circumstances of the battle. His work is mostly based on manuscripts written at the time of the battle, but since lost. Aventinus mentioned the event in two paragraphs. [1] At first, he wrote: "The Hungarians demand tax payment from Arnulf, who refuses it. After that they invade the Bavarians. Arnulf surrounds and slaughters them". In the second paragraph, Aventinus has more detailed the events:

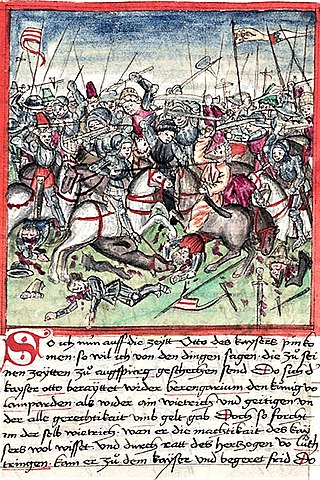

The Hungarians were there in every place of risk, demanding new tax payment both from Arnulf and King Conrad. They threatened if it will be refused, as Louis [the Child] did, they get torn everything to the ground. Arnulf replies to the envoys in the following manner: «I, he said, reign since my early youth, I did not learn to obey. If Hungarians come, we take up weapons, he flaunted, and they will experience the strength of our hands in a battle.» Hearing this, the Hungarians promptly invaded Bavaria with their large number of cavalry. Arnulf, who avoids [direct] combat, commands [his men] to retreat to protected sites with their belongings and equipment. He hides scattered [his] soldiers, knights beyond the forests, marshes and the threatened land of Noricum into ambuscades: [then] he appears leading a small number of selected riders near the enemy and, turning back, simulates fleeing.

— Annalium Boiorum

Aventinus' narrative confirmed that Conrad was obliged to pay tribute to the Hungarians, as well as his predecessor Louis the Child, together with the Swabian, Frankish, Bavarian and Saxonian dukes, after the Battle of Rednitz in June 910. According to the chronicler, paying the regular tax was the "price of peace". After the western border was pacified, the Hungarians used the Eastern provinces of the Kingdom of Germany as puffer zone and transfer area to execute their long-range military campaigns to far West. [2] Bavaria allowed Hungarians into their realm to continue their journey and the Bavarian–Hungarian relations were described as neutral during this time. Following the disastrous Battle of Pressburg (907), Arnulf strengthened his power through confiscation of church lands and the secularization of numerous monastery estates to raise funds to finance a re-organized defense, which earned him the nickname "the Bad" by medieval chroniclers. Despite "peace" which was guaranteed by regular tax payments, he was faced with constant raids from the Hungarians, when they entered the border or returned to the Pannonian Basin after a distant campaign. However the energetic and combative Arnulf already defeated a small Hungarian raiding contingent at Pocking near the Rott river on 11 August 909, after they withdrew from a campaign where they burnt the two churches of Freising. In 910, he also beat another minor Hungarian unit at Neuching, which returned from the victorious Battle of Lechfeld and other plundering attacks. [2]

Historian István Bóna described the battle as a "destruction of a gang of robbers" who arbitrarily broke the conditions of peace. [3] Other historians, who argue in favour of the lack of central organization of military campaigns, consider the Hungarian plunder attack in Bavaria after returning their war from West, which resulted Battle of the Inn, was merely a private action by a tribal chieftain or a small unit. Historian Levente Igaz argues the Bavarian was able to achieve success against the Hungarians only if they returned from a prosperous remote campaign with their booty, prisoners, and livestock which slowed down their marching. [2] It is possible that after years of peace and stabilization, Arnulf felt strong enough to create new favorable conditions for his forced alliance with the Hungarians. After his disobedient behavior, the Hungarians launched a punitive expedition against his duchy, provoking a war. His conscious strategy was confirmed by the report of the Annales Alamannici, which wrote Arnulf concluded an alliance with his relatives, Swabian counts Erchanger and Burchard, and an influential lord Udalrich against the Hungarians. [4] Aventinus' work also suggests that Arnulf used the Hungarians' "own military method" when ordered they soldiers to hide and imitating retreat, confirming a military cultural exchange at the Bavarian–Hungarian border. [5]