Related Research Articles

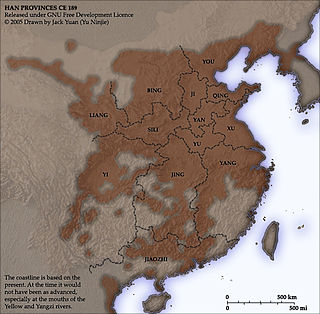

Middle Chinese or the Qieyun system (QYS) is the historical variety of Chinese recorded in the Qieyun, a rime dictionary first published in 601 and followed by several revised and expanded editions. The Swedish linguist Bernhard Karlgren believed that the dictionary recorded a speech standard of the capital Chang'an of the Sui and Tang dynasties. However, based on the preface of the Qieyun, most scholars now believe that it records a compromise between northern and southern reading and poetic traditions from the late Northern and Southern dynasties period. This composite system contains important information for the reconstruction of the preceding system of Old Chinese phonology.

Fanqie is a method in traditional Chinese lexicography to indicate the pronunciation of a monosyllabic character by using two other characters, one with the same initial consonant as the desired syllable and one with the same rest of the syllable . The method was introduced in the 3rd century AD and is to some extent still used in commentaries on the classics and dictionaries.

A rime table or rhyme table is a Chinese phonological model, tabulating the syllables of the series of rime dictionaries beginning with the Qieyun (601) by their onsets, rhyme groups, tones and other properties. The method gave a significantly more precise and systematic account of the sounds of those dictionaries than the previously used fǎnqiè analysis, but many of its details remain obscure. The phonological system that is implicit in the rime dictionaries and analysed in the rime tables is known as Middle Chinese, and is the traditional starting point for efforts to recover the sounds of early forms of Chinese. Some authors distinguish the two layers as Early and Late Middle Chinese respectively.

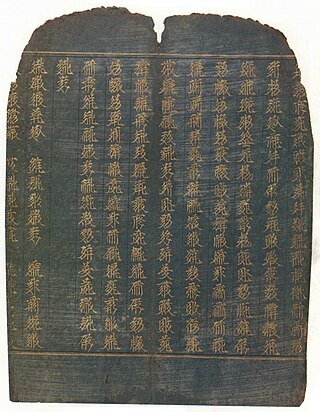

The Qieyun is a Chinese rime dictionary that was published in 601 during the Sui dynasty. The book was a guide to proper reading of classical texts, using the fanqie method to indicate the pronunciation of Chinese characters. The Qieyun and later redactions, notably the Guangyun, are important documentary sources used in the reconstruction of historical Chinese phonology.

The Guangyun is a Chinese rime dictionary that was compiled from 1007 to 1008 under the patronage of Emperor Zhenzong of Song. Its full name was Dà Sòng chóngxiū guǎngyùn. Chen Pengnian and Qiu Yong (邱雍) were the chief editors.

A rime dictionary, rhyme dictionary, or rime book is an ancient type of Chinese dictionary that collates characters by tone and rhyme, instead of by radical. The most important rime dictionary tradition began with the Qieyun (601), which codified correct pronunciations for reading the classics and writing poetry by combining the reading traditions of north and south China. This work became very popular during the Tang dynasty, and went through a series of revisions and expansions, of which the most famous is the Guangyun (1007–1008).

Historical Chinese phonology deals with reconstructing the sounds of Chinese from the past. As Chinese is written with logographic characters, not alphabetic or syllabary, the methods employed in Historical Chinese phonology differ considerably from those employed in, for example, Indo-European linguistics; reconstruction is more difficult because, unlike Indo-European languages, no phonetic spellings were used.

Tangut is an extinct language in the Sino-Tibetan language family.

General Chinese is a diaphonemic orthography invented by Yuen Ren Chao to represent the pronunciations of all major varieties of Chinese simultaneously. It is "the most complete genuine Chinese diasystem yet published". It can also be used for the Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese pronunciations of Chinese characters, and challenges the claim that Chinese characters are required for interdialectal communication in written Chinese.

Sino-Xenic or Sinoxenic pronunciations are regular systems for reading Chinese characters in Japan, Korea and Vietnam, originating in medieval times and the source of large-scale borrowings of Chinese words into the Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese languages, none of which are genetically related to Chinese. The resulting Sino-Japanese, Sino-Korean and Sino-Vietnamese vocabularies now make up a large part of the lexicons of these languages. The pronunciation systems are used alongside modern varieties of Chinese in historical Chinese phonology, particularly the reconstruction of the sounds of Middle Chinese. Some other languages, such as Hmong–Mien and Kra–Dai languages, also contain large numbers of Chinese loanwords but without the systematic correspondences that characterize Sino-Xenic vocabularies.

The Yunjing is one of the two oldest existing examples of a Chinese rime table – a series of charts which arrange Chinese characters in large tables according to their tone and syllable structures to indicate their proper pronunciations. Current versions of the Yunjing date to AD 1161 and 1203 editions published by Zhang Linzhi (張麟之). The original author(s) and date of composition of the Yunjing are unknown. Some of its elements, such as certain choices in its ordering, reflect features particular to the Tang dynasty, but no conclusive proof of an actual date of composition has yet been found.

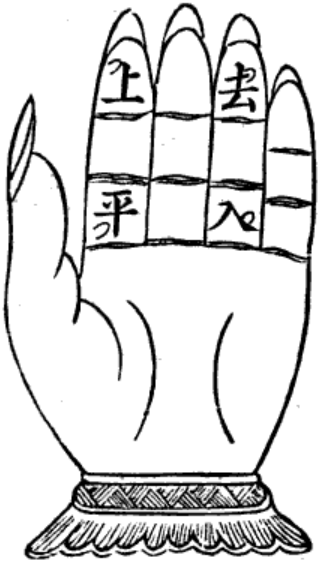

The four tones of Chinese poetry and dialectology are four traditional tone classes of Chinese words. They play an important role in Chinese poetry and in comparative studies of tonal development in the modern varieties of Chinese, both in traditional Chinese and in Western linguistics. They correspond to the phonology of Middle Chinese, and are named even or level, rising, departing or going, and entering or checked. They are reconstructed as mid, mid rising, high falling, and mid with a final stop consonant respectively. Due to historic splits and mergers, none of the modern varieties of Chinese have the exact four tones of Middle Chinese, but they are noted in rhyming dictionaries.

Chóngniǔ or rime doublets are certain pairs of Middle Chinese syllables that are consistently distinguished in rime dictionaries and rime tables, but without a clear indication of the phonological basis of the distinction.

Old Mandarin or Early Mandarin was the speech of northern China during the Jurchen-ruled Jin dynasty and the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. New genres of vernacular literature were based on this language, including verse, drama and story forms, such as the qu and sanqu.

Scholars have attempted to reconstruct the phonology of Old Chinese from documentary evidence. Although the writing system does not describe sounds directly, shared phonetic components of the most ancient Chinese characters are believed to link words that were pronounced similarly at that time. The oldest surviving Chinese verse, in the Classic of Poetry (Shijing), shows which words rhymed in that period. Scholars have compared these bodies of contemporary evidence with the much later Middle Chinese reading pronunciations listed in the Qieyun rime dictionary published in 601 AD, though this falls short of a phonemic analysis. Supplementary evidence has been drawn from cognates in other Sino-Tibetan languages and in Min Chinese, which split off before the Middle Chinese period, Chinese transcriptions of foreign names, and early borrowings from and by neighbouring languages such as Hmong–Mien, Tai and Tocharian languages.

The Karlgren–Li reconstruction of Middle Chinese was a representation of the sounds of Middle Chinese devised by Bernhard Karlgren and revised by Li Fang-Kuei in 1971, remedying a number of minor defects.

In Middle Chinese, the phonological system of medieval rime dictionaries and rime tables, the final is the rest of the syllable after the initial consonant. This analysis is derived from the traditional Chinese fanqie system of indicating pronunciation with a pair of characters indicating the sounds of the initial and final parts of the syllable respectively, though in both cases several characters were used for each sound. Reconstruction of the pronunciation of finals is much more difficult than for initials due to the combination of multiple phonemes into a single class, and there is no agreement as to their values. Because of this lack of consensus, understanding of the reconstruction of finals requires delving into the details of rime tables and rime dictionaries.

Although Old Chinese is known from written records beginning around 1200 BC, the logographic script provides much more indirect and partial information about the pronunciation of the language than alphabetic systems used elsewhere. Several authors have produced reconstructions of Old Chinese phonology, beginning with the Swedish sinologist Bernhard Karlgren in the 1940s and continuing to the present day. The method introduced by Karlgren is unique, comparing categories implied by ancient rhyming practice and the structure of Chinese characters with descriptions in medieval rhyme dictionaries, though more recent approaches have also incorporated other kinds of evidence.

The Shenglei 聲類, compiled by the Cao Wei dynasty lexicographer Li Deng 李登, was the first Chinese rime dictionary. Earlier dictionaries were organized either by semantic fields or by character radicals. The last copies of the Shenglei were lost around the 13th century, and it is known only from earlier descriptions and quotations, which say it was in 10 volumes and contained 11,520 Chinese character entries, categorized by linguistic tone in terms of the wǔshēng 五聲 "Five Tones " from Chinese musicology and wǔxíng 五行 "Five Phases/Elements" theory.

Eastern Han Chinese, Later Han Chinese or Late Old Chinese is the stage of the Chinese language revealed by poetry and glosses from the Eastern Han period . It is considered an intermediate stage between Old Chinese and the Middle Chinese of the 7th-century Qieyun dictionary.

References

Citations

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 24–28.

- ↑ Baxter (1992), pp. 33–40.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 28–34.

- ↑ Baxter (1992), pp. 41–43.

- ↑ Baxter (1992), pp. 69–81.

- ↑ Baxter (1992), pp. 27, 818–819.

- ↑ Branner (2006), p. 269.

- ↑ Baxter (1992), pp. 45–46.

- ↑ Baxter (1992), p. 81.

- ↑ Baxter (1992), p. 31.

- ↑ Baxter (1992), p. 821.

- ↑ Baxter (1992), pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Baxter (1992), pp. 31–32.

Works cited

- Baxter, William H. (1992), A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-012324-1.

- Branner, David Prager (2006), "Appendix II: Comparative Transcriptions of Rime Table Phonology", in Branner, David Prager (ed.), The Chinese Rime Tables: Linguistic Philosophy and Historical-Comparative Phonology, Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 265–302, ISBN 978-90-272-4785-8.

- Norman, Jerry (1988), Chinese, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29653-3.