When it grew late and we had been drinking wine for most of the evening, we began discussing the sounds and the rhymes. Modern pronunciations are naturally varied; moreover, those who have written on the sounds and the rhymes have not always been in agreement. ...

So we discussed the rights and wrongs of the North and the South and the comprehensible and incomprehensible of the ancients and moderns. We wanted to select the precise and discard the extraneous, ...

So under the candlelight I took up the brush and jotted down an outline. We consulted each other extensively and argued vigorously. We came close to getting the essence.

— Lu Fayan, Qieyun, preface, translated by S. Robert Ramsey [1]

None of these scholars was originally from Chang'an; they were native speakers of differing dialects – five northern and three southern. [2] [3] According to Lu, Yan Zhitui (顏之推) and Xiao Gai (蕭該), both men originally from the south, were the most influential in setting up the norms on which the Qieyun was based. [2] However, the dictionary was compiled by Lu alone, consulting several earlier dictionaries, none of which have survived. [4]

When classical Chinese poetry flowered during the Tang dynasty, the Qieyun became the authoritative source for literary pronunciations and it repeatedly underwent revisions and enlargements. It was annotated in 677 by Zhǎngsūn Nèyá長孫訥言), revised and published in 706 by Wáng Renxu (王仁煦) as the Kanmiu Buque Qieyun (刊謬補缺切韻; "Corrected and supplemented Qieyun"), collated and republished in 751 by Sun Mian (孫愐) as the Tángyùn (唐韻; "Tang rimes"), and eventually incorporated into the still-extant Guangyun and Jiyun rime dictionaries from the Song dynasty. [5] Although most of these Tang dictionary redactions were believed lost, some fragments were discovered among the Dunhuang manuscripts and manuscripts discovered at Turpan. [5] [6]

The Qieyun reflected the enhanced phonological awareness that developed in China after the advent of Buddhism, which introduced the sophisticated Indian linguistics. [7] The Buddhist Uyghur Kingdom of Qocho used a version of the Qieyun. [8]

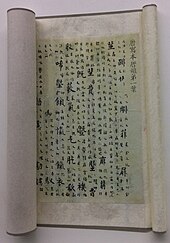

During the Tang dynasty, several copyists were engaged in producing manuscripts to meet the great demand for revisions of the work. Particularly prized were copies of Wáng Rénxū's edition made in the early 9th century by Wú Cǎiluán (吳彩鸞), a woman famed for her calligraphy. [9] One of these copies was acquired by Emperor Huizong (1100–1126), himself a keen calligrapher. It remained in the palace library until 1926, when part of the library followed the deposed emperor Puyi to Tianjin and then to Changchun, capital of the puppet state of Manchukuo. After the Japanese surrender in 1945, it passed to a book dealer in Changchun, and in 1947 two scholars discovered it in a book market in Liulichang, Beijing. [10]

Studies of this almost complete copy have been published by the Chinese linguists Dong Tonghe (1948 and 1952) and Li Rong (1956). [11]

Structure

The Qieyun contains 12,158 character entries. [12] These were divided into five volumes, two for the many words of the "level" tone, and one volume for each of the other three tones. The entries were divided into 193 final rhyme groups (each named by its first character, called the yùnmù 韻目, or "rhyme eye"). Each rhyme group was subdivided into homophone groups (xiǎoyùn 小韻 "small rhyme"). The first entry in each homophone group gives the pronunciation as a fanqie formula. [13] [14]

For example, the first entry in the Qieyun, shown at right, describes the character 東 dōng "east". The three characters on the right are a fanqie pronunciation key, marked by the character 反 fǎn "turn back". This indicates that the word is pronounced with the initial of 德 [tək] and the final of 紅 [ɣuŋ], i.e. [tuŋ]. The word is glossed as 木方 mù fāng, i.e. the direction of wood (one of the Five Elements), while the numeral 二 "two" indicates that this is the first of two entries in a homophone group.

Later rime dictionaries had many more entries, with full definitions and a few additional rhyme groups, but kept the same structure. [15]

The Qieyun did not directly record Middle Chinese as a spoken language, but rather how characters should be pronounced when reading the classics. Since this rime dictionary's spellings are the primary source for reconstructing Middle Chinese, linguists have disagreed over what variety of Chinese it recorded. "Much ink has been spilled concerning the nature of the language underlying the Qieyun," says Norman (1988: 24), who lists three points of view. Some scholars, like Bernhard Karlgren, "held to the view that the Qieyun represented the language of Chang'an"; some "others have supposed that it represented an amalgam of regional pronunciations," technically known as a diasystem. "At the present time most people in the field accept the views of the Chinese scholar Zhou Zumo" (周祖謨; 1914–1995) that Qieyun spellings were a north–south regional compromise between literary pronunciations from the Northern and Southern dynasties.

See also

Related Research Articles

Middle Chinese or the Qieyun system (QYS) is the historical variety of Chinese recorded in the Qieyun, a rime dictionary first published in 601 and followed by several revised and expanded editions. The Swedish linguist Bernard Karlgren believed that the dictionary recorded a speech standard of the capital Chang'an of the Sui and Tang dynasties. However, based on the preface of the Qieyun, most scholars now believe that it records a compromise between northern and southern reading and poetic traditions from the late Northern and Southern dynasties period. This composite system contains important information for the reconstruction of the preceding system of Old Chinese phonology.

Fanqie is a method in traditional Chinese lexicography to indicate the pronunciation of a monosyllabic character by using two other characters, one with the same initial consonant as the desired syllable and one with the same rest of the syllable . The method was introduced in the 3rd century AD and is to some extent still used in commentaries on the classics and dictionaries.

A rime table or rhyme table is a Chinese phonological model, tabulating the syllables of the series of rime dictionaries beginning with the Qieyun (601) by their onsets, rhyme groups, tones and other properties. The method gave a significantly more precise and systematic account of the sounds of those dictionaries than the previously used fǎnqiè analysis, but many of its details remain obscure. The phonological system that is implicit in the rime dictionaries and analysed in the rime tables is known as Middle Chinese, and is the traditional starting point for efforts to recover the sounds of early forms of Chinese. Some authors distinguish the two layers as Early and Late Middle Chinese respectively.

The Guangyun is a Chinese rime dictionary that was compiled from 1007 to 1008 under the patronage of Emperor Zhenzong of Song. Its full name was Dà Sòng chóngxiū guǎngyùn. Chen Pengnian and Qiu Yong (邱雍) were the chief editors.

A rime dictionary, rhyme dictionary, or rime book is an ancient type of Chinese dictionary that collates characters by tone and rhyme, instead of by radical. The most important rime dictionary tradition began with the Qieyun (601), which codified correct pronunciations for reading the classics and writing poetry by combining the reading traditions of north and south China. This work became very popular during the Tang dynasty, and went through a series of revisions and expansions, of which the most famous is the Guangyun (1007–1008).

Historical Chinese phonology deals with reconstructing the sounds of Chinese from the past. As Chinese is written with logographic characters, not alphabetic or syllabary, the methods employed in Historical Chinese phonology differ considerably from those employed in, for example, Indo-European linguistics; reconstruction is more difficult because, unlike Indo-European languages, no phonetic spellings were used.

Tangut is an extinct language in the Sino-Tibetan language family.

Zhongyuan Yinyun, literally meaning "Rhymes of the central plain", is a rime book from the Yuan dynasty compiled by Zhou Deqing (周德清) in 1324. An important work for the study of historical Chinese phonology, it testifies many phonological changes from Middle Chinese to Old Mandarin, such as the reduction and disappearance of final stop consonants and the reorganization of the Middle Chinese tones. Though often termed a "rime dictionary", the work does not provide meanings for its entries.

The Yunjing is one of the two oldest existing examples of a Chinese rime table – a series of charts which arrange Chinese characters in large tables according to their tone and syllable structures to indicate their proper pronunciations. Current versions of the Yunjing date to AD 1161 and 1203 editions published by Zhang Linzhi (張麟之). The original author(s) and date of composition of the Yunjing are unknown. Some of its elements, such as certain choices in its ordering, reflect features particular to the Tang dynasty, but no conclusive proof of an actual date of composition has yet been found.

Chóngniǔ or rime doublets are certain pairs of Middle Chinese syllables that are consistently distinguished in rime dictionaries and rime tables, but without a clear indication of the phonological basis of the distinction.

The Karlgren–Li reconstruction of Middle Chinese was a representation of the sounds of Middle Chinese devised by Bernhard Karlgren and revised by Li Fang-Kuei in 1971, remedying a number of minor defects.

William H. Baxter's transcription for Middle Chinese is an alphabetic notation recording phonological information from medieval sources, rather than a reconstruction. It was introduced by Baxter as a reference point for his reconstruction of Old Chinese phonology.

In Middle Chinese, the phonological system of medieval rime dictionaries and rime tables, the final is the rest of the syllable after the initial consonant. This analysis is derived from the traditional Chinese fanqie system of indicating pronunciation with a pair of characters indicating the sounds of the initial and final parts of the syllable respectively, though in both cases several characters were used for each sound. Reconstruction of the pronunciation of finals is much more difficult than for initials due to the combination of multiple phonemes into a single class, and there is no agreement as to their values. Because of this lack of consensus, understanding of the reconstruction of finals requires delving into the details of rime tables and rime dictionaries.

The Tangyun is a Chinese rime dictionary, published in 732 CE during the Tang dynasty, by Sun Mian (孫愐), which is a revised version of Qieyun, a guide for Chinese pronunciation by using the fanqie method. The original has lost. According to Shigutang Shuhua Huikao (式古堂書畫匯考) by Bian Yongyu (卞永譽), Tangyun has 5 volumes, 195 rimes totally. The statistics is the same as from Kanmiu Buque Qieyun (刊謬補缺切韻) by Wang Renxu (王仁昫), which has respectively one more rimes in Shangshen (上聲) and Qusheng (去聲) than Qieyun.

The Shenglei 聲類, compiled by the Cao Wei dynasty lexicographer Li Deng 李登, was the first Chinese rime dictionary. Earlier dictionaries were organized either by semantic fields or by character radicals. The last copies of the Shenglei were lost around the 13th century, and it is known only from earlier descriptions and quotations, which say it was in 10 volumes and contained 11,520 Chinese character entries, categorized by linguistic tone in terms of the wǔshēng 五聲 "Five Tones " from Chinese musicology and wǔxíng 五行 "Five Phases/Elements" theory.

The Yiqiejing yinyi is the oldest surviving Chinese dictionary of Buddhist technical terminology, and was the archetype for later Chinese bilingual dictionaries. This specialized glossary was compiled by the Tang dynasty lexicographer monk Xuanying (玄應), who was a translator for the famous pilgrim and Sanskritist monk Xuanzang. When Xuanying died he had only finished 25 chapters of the dictionary, but another Tang monk Huilin (慧琳) compiled an enlarged 100-chapter version with the same title, the (807) Yiqiejing yinyi.

The Yiqiejing yinyi 一切經音義 "Pronunciation and Meaning in the Complete Buddhist Canon" was compiled by the Tang dynasty lexicographer monk Huilin 慧琳 as an expanded revision of the original Yiqiejing yinyi compiled by Xuanying 玄應. Collectively, Xuanying's 25-chapter and Huilin's 100-chapter versions constitute the oldest surviving Chinese dictionary of Buddhist technical terminology. A recent history of Chinese lexicography call Huilin's Yiqiejing yinyi "a composite collection of all the glossaries of scripture words and expressions compiled in and before the Tang Dynasty" and "the archetype of the Chinese bilingual dictionary".

Shǒuwēn was a 9th-century Buddhist Chinese monk credited with the invention of the analysis of Middle Chinese as having 36 initials, later ubiquitously used by the rime tables. However, the Dunhuang fragment Pelliot chinois 2012, held at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, which operates using an earlier tradition of 30 initials, credits him as his author. Pulleyblank, noting that this fragment does recognize a distinction between labial stops and labiodental fricatives despite not enumerating the latter among the 30 initials, suspects that Shǒuwēn out of deference to the Qieyun tradition decided not to list these initials although he clearly recognized them.

The Kanmiu Buque Qieyun (刊謬補缺切韻) by Wang Renxu (王仁昫), which was published in 706, is the oldest extant Chinese rime dictionary. For many centuries, it was believed to be lost, until a copy was found at the imperial palace in Beijing in 1947. Lóng 1968 published an eye copy with annotations. Zhou 1983: 434-527 includes a facsimile of the original, which is not very legible.

The Pingshui Rhyming Scheme is a rhyming system of the Middle Chinese language. Compiled in the Jin dynasty, Pingshui Yun is one of the most popular rhyming systems in Chinese poetry after the Tang dynasty and the official standard in later dynasties.

References

Citations

- ↑ Ramsey (1987), pp. 116–117.

- 1 2 Norman (1988), p. 25.

- ↑ Baxter (1992), p. 37.

- ↑ Coblin (1996), pp. 89–90.

- 1 2 Baxter (1992), pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Bottéro (2013), pp. 35–37.

- ↑ Mair (1998), p. 168.

- ↑ Takata (2004), p. 337.

- ↑ Takata (2004), p. 333.

- ↑ Malmqvist (2010), pp. 299–300.

- ↑ Baxter (1992), p. 39.

- ↑ Pulleyblank (1984), p. 139.

- ↑ Takata (2004).

- ↑ Baxter (1992), pp. 33–35.

- ↑ Baxter (1992), p. 33.

Works cited

- Baxter, William H. (1992), A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-012324-1.

- Bottéro, François (2013), "The Qièyùn manuscripts from Dūnhuáng", in Galambos, Imre (ed.), Studies in Chinese Manuscripts: From the Warring States Period to the 20th Century (PDF), Budapest: Eötvös Loránd University, pp. 33–48, ISBN 978-963-284-326-1.

- Coblin, W. South (1996), "Marginalia on two translations of the Qieyun preface" (PDF), Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 24 (1): 85–97, JSTOR 23753994.

- Mair, Victor H. (1998), "Tzu-shu 字書 or tzu-tien 字典 (dictionaries)", in Nienhauser, William H. (ed.), The Indiana Companion to Traditional Chinese Literature (Volume 2), Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 165–172, ISBN 978-025-333-456-5.

- Malmqvist, Göran (2010), Bernhard Karlgren: Portrait of a Scholar, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-1-61146-001-8.

- Norman, Jerry (1988), Chinese, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29653-3.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (1984), Middle Chinese: a study in historical phonology, Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, ISBN 978-0-7748-0192-8.

- Ramsey, S. Robert (1987), The Languages of China, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-01468-5.

- Takata, Tokio (2004), "The Chinese Language in Turfan with a special focus on the Qieyun fragments" (PDF), in Durkin, Desmond (ed.), Turfan revisited: the first century of research into the arts and cultures of the Silk Road, pp. 333–340, ISBN 978-3-496-02763-8.

External links

- A comprehensive parallel presentation of various Qieyun fragments and editions, by Suzuki Shingo 鈴木 慎吾

- Qieyun fragments found at Dunhuang by Paul Pelliot, now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France:

- Pelliot chinois 2019 (BNF link): prefaces of Lu Fayan (start missing), Zhangsun Neyan (complete) and Sun Mian (end missing)

- Pelliot chinois 2017 (BNF link): part of Lu Fayan's preface, rhyme index and start of the first rhyme group (東 dōng)

- Pelliot chinois 3799 (BNF link): fragment of volume 5 showing the 怗 tiē, 緝 qì and 藥 yào rhyme groups

- Qieyun fragments brought from Dunhuang by Aurel Stein, now in the British Library (only S.2071, S.5980 and S.6156 have been scanned):

- Or.8210/S.2071: substantial portion of the level, rising and entering tones.

- Or.8210/S.2055: Zhangsun Neyan's preface (dated 677) and first 9 rhymes of the level tone, with somewhat fuller entries than S.2071.

- smaller fragments: Or.8210/S.2683, Or.8210/S.6176, Or.8210/S.5980, Or.8210/S.6156, Or.8210/S.6012, Or.8210/S.6013, Or.8210/S.6187.

- Qieyun fragments from Turfan, Tuyoq and Kucha, now in the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities (in the IDP Database Advanced Search, select "Short Title" and choose "Qie yun or Rhyme dictionary"; see Takata (2004) for discussion):

| Qieyun | |

|---|---|

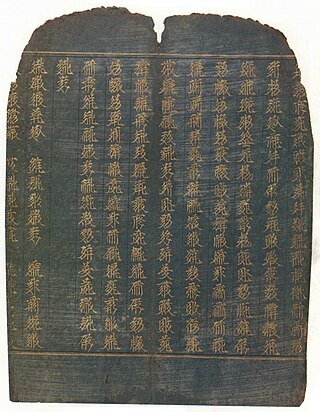

Qieyun excerpt in the Chinese Dictionary Museum, Jincheng, Shanxi |