Related Research Articles

Klas Bernhard Johannes Karlgren was a Swedish sinologist and linguist who pioneered the study of Chinese historical phonology using modern comparative methods. In the early 20th century, Karlgren conducted large surveys of the varieties of Chinese and studied historical information on rhyming in ancient Chinese poetry, then used them to create the first ever complete reconstructions of what are now called Middle Chinese and Old Chinese.

Middle Chinese or the Qieyun system (QYS) is the historical variety of Chinese recorded in the Qieyun, a rime dictionary first published in 601 and followed by several revised and expanded editions. The Swedish linguist Bernhard Karlgren believed that the dictionary recorded a speech standard of the capital Chang'an of the Sui and Tang dynasties. However, based on the preface of the Qieyun, most scholars now believe that it records a compromise between northern and southern reading and poetic traditions from the late Northern and Southern dynasties period. This composite system contains important information for the reconstruction of the preceding system of Old Chinese phonology.

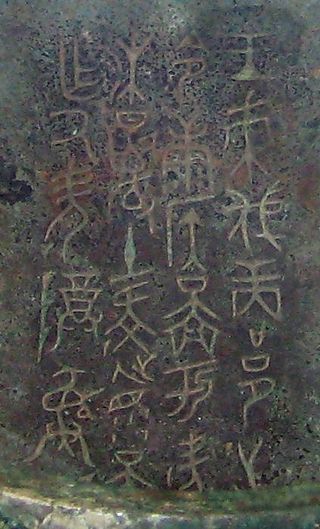

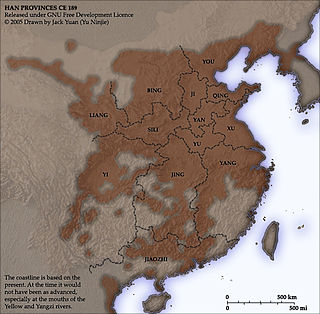

Old Chinese, also called Archaic Chinese in older works, is the oldest attested stage of Chinese, and the ancestor of all modern varieties of Chinese. The earliest examples of Chinese are divinatory inscriptions on oracle bones from around 1250 BC, in the Late Shang period. Bronze inscriptions became plentiful during the following Zhou dynasty. The latter part of the Zhou period saw a flowering of literature, including classical works such as the Analects, the Mencius, and the Zuo Zhuan. These works served as models for Literary Chinese, which remained the written standard until the early twentieth century, thus preserving the vocabulary and grammar of late Old Chinese.

Xu Shen was a Chinese calligrapher, philologist, politician, and writer of the Eastern Han dynasty. During his own lifetime, Xu was recognized as a preeminent scholar of the Five Classics. He was the author of Shuowen Jiezi, which was the first comprehensive dictionary of Chinese characters, as well as the first to organize entries by radical. This work continues to provide scholars with information on the development and historical usage of Chinese characters. Xu Shen completed his first draft in 100 CE but, waited until 121 CE before having his son present the work to the Emperor An of Han.

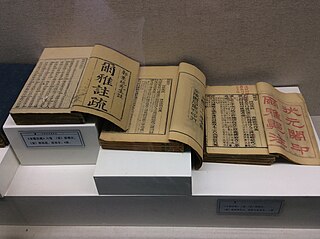

Duan Yucai (1735–1815), courtesy name Ruoying (若膺) was a Chinese philologist of the Qing Dynasty. He made great contributions to the study of Historical Chinese phonology, and is known for his annotated edition of Shuowen Jiezi.

Historical Chinese phonology deals with reconstructing the sounds of Chinese from the past. As Chinese is written with logographic characters, not alphabetic or syllabary, the methods employed in Historical Chinese phonology differ considerably from those employed in, for example, Indo-European linguistics; reconstruction is more difficult because, unlike Indo-European languages, no phonetic spellings were used.

The Erya or Erh-ya is the first surviving Chinese dictionary. The sinologist Bernhard Karlgren concluded that "the major part of its glosses must reasonably date from the 3rd century BC."

The Dongyi or Eastern Yi was a collective term for ancient peoples found in Chinese records. The definition of Dongyi varied across the ages, but in most cases referred to inhabitants of eastern China, then later, the Korean peninsula and Japanese Archipelago. Dongyi refers to different group of people in different periods. As such, the name "Yí" 夷 was something of a catch-all and was applied to different groups over time. According to the earliest Chinese record, the Zuo Zhuan, the Shang dynasty was attacked by King Wu of Zhou while attacking the Dongyi and collapsed afterward.

Qiulong or qiu was a Chinese dragon that is contradictorily defined as "horned dragon" and "hornless dragon".

There are two types of dictionaries regularly used in the Chinese language: 'character dictionaries' list individual Chinese characters, and 'word dictionaries' list words and phrases. Because tens of thousands of characters have been used in written Chinese, Chinese lexicographers have developed a number of methods to order and sort characters to facilitate more convenient reference.

Chi means either "a hornless dragon" or "a mountain demon" in Chinese mythology. Hornless dragons were a common motif in ancient Chinese art, and the chiwen 螭吻 was an imperial roof decoration in traditional Chinese architecture.

Teng or Tengshe is a flying dragon in Chinese mythology.

A xiesheng or phonological series is a set of Chinese characters sharing the same sound-based element. Characters belonging to these series are generally phono-semantic compounds, where the character is composed of a semantic element and a sound-based element, encoding information about the meaning and the pronunciation respectively.

Scholars have attempted to reconstruct the phonology of Old Chinese from documentary evidence. Although the writing system does not describe sounds directly, shared phonetic components of the most ancient Chinese characters are believed to link words that were pronounced similarly at that time. The oldest surviving Chinese verse, in the Classic of Poetry (Shijing), shows which words rhymed in that period. Scholars have compared these bodies of contemporary evidence with the much later Middle Chinese reading pronunciations listed in the Qieyun rime dictionary published in 601 AD, though this falls short of a phonemic analysis. Supplementary evidence has been drawn from cognates in other Sino-Tibetan languages and in Min Chinese, which split off before the Middle Chinese period, Chinese transcriptions of foreign names, and early borrowings from and by neighbouring languages such as Hmong–Mien, Tai and Tocharian languages.

The Karlgren–Li reconstruction of Middle Chinese was a representation of the sounds of Middle Chinese devised by Bernhard Karlgren and revised by Li Fang-Kuei in 1971, remedying a number of minor defects.

In Middle Chinese, the phonological system of medieval rime dictionaries and rime tables, the final is the rest of the syllable after the initial consonant. This analysis is derived from the traditional Chinese fanqie system of indicating pronunciation with a pair of characters indicating the sounds of the initial and final parts of the syllable respectively, though in both cases several characters were used for each sound. Reconstruction of the pronunciation of finals is much more difficult than for initials due to the combination of multiple phonemes into a single class, and there is no agreement as to their values. Because of this lack of consensus, understanding of the reconstruction of finals requires delving into the details of rime tables and rime dictionaries.

Although Old Chinese is known from written records beginning around 1200 BC, the logographic script provides much more indirect and partial information about the pronunciation of the language than alphabetic systems used elsewhere. Several authors have produced reconstructions of Old Chinese phonology, beginning with the Swedish sinologist Bernhard Karlgren in the 1940s and continuing to the present day. The method introduced by Karlgren is unique, comparing categories implied by ancient rhyming practice and the structure of Chinese characters with descriptions in medieval rhyme dictionaries, though more recent approaches have also incorporated other kinds of evidence.

Pu is a Chinese word meaning "unworked wood; inherent quality; simple" that was an early Daoist metaphor for the natural state of humanity, and relates with the Daoist keyword ziran "natural; spontaneous". The scholar Ge Hong immortalized pu in his pen name Baopuzi "Master who Embraces Simplicity" and eponymous book Baopuzi.

Eastern Han Chinese, Later Han Chinese or Late Old Chinese is the stage of the Chinese language revealed by poetry and glosses from the Eastern Han period . It is considered an intermediate stage between Old Chinese and the Middle Chinese of the 7th-century Qieyun dictionary.

The Shuowen tongxun dingsheng is an 18-volume study of the Shuowen Jiezi completed in 1833 by the Qing phonologist Zhu Junsheng (朱駿聲) (1788–1858) and published in 1870. The bulk of the work is a phonetic study in which the 9000 characters of the Shuowen Jiezi and 7000 additional characters are grouped into 1137 series, each sharing a phonetic element. These phonetic series were further grouped into 18 Shijing rhyme groups, based on Duan Yucai's dictum that characters sharing a phonetic element belonged in the same rhyme group. The work thus anticipated the structure of Bernard Karlgren's Grammata Serica Recensa. The work also includes very detailed notes on rhyming, semantics, and interchangeable characters.

References

- ↑ Karlgren, Bernhard (1957), Grammata Serica Recensa, Stockholm: Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, OCLC 1999753.

- ↑ Malmqvist, N. G. D. (2011). Bernhard Karlgren: Portrait of a Scholar. Bethlehem, PA; Lanham, MD: Lehigh University Press; Rowman & Littlefield. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-61146-001-8. Translation of Göran Malmqvist, Bernhard Karlgren: ett forskarporträtt [Bernhard Karlgren: Portrait of a Scholar], Stockholm: Norstedts. 1995.

- ↑ Karlgren, Bernhard (1923), Analytic dictionary of Chinese and Sino-Japanese, Paris: Paul Geuthner, ISBN 978-0-486-21887-8.

- ↑ Karlgren (1957), pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Wagner, Donald B. (1998), A classical Chinese reader, Routledge, p. 6, ISBN 978-0-7007-0960-1.

- ↑ Schuessler, Axel (2009), Minimal Old Chinese and later Han Chinese: a companion to Grammata serica recensa, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-3264-3.

- ↑ Sino-Tibetan Etymological Dictionary and Thesaurus Home Page, University of California at Berkeley.

- ↑ Jenkins, John H.; Cook, Richard (2010), "Unicode Standard Annex #38: Unicode Han Database", The Unicode Standard – Version 6.0, Unicode Consortium.