Related Research Articles

The Long Walk of the Navajo, also called the Long Walk to Bosque Redondo, was the 1864 deportation and attempted ethnic cleansing of the Navajo people by the United States federal government. Navajos were forced to walk from their land in what is now Arizona to eastern New Mexico. Some 53 different forced marches occurred between August 1864 and the end of 1866. Some anthropologists claim that the "collective trauma of the Long Walk...is critical to contemporary Navajos' sense of identity as a people".

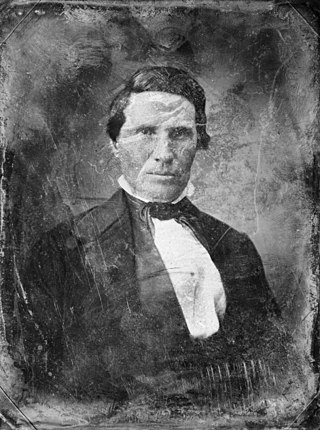

Alexander William Doniphan was a 19th-century American attorney, soldier and politician from Missouri who is best known today as the man who prevented the summary execution of Joseph Smith, founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, at the close of the 1838 Mormon War in that state. He also achieved renown as a leader of American troops during the Mexican–American War, as the author of a legal code that still forms the basis of New Mexico's Bill of Rights, and as a successful defense attorney in the Missouri towns of Liberty, Richmond and Independence.

The Apache Wars were a series of armed conflicts between the United States Army and various Apache tribal confederations fought in the southwest between 1849 and 1886, though minor hostilities continued until as late as 1924. After the Mexican–American War in 1846, the United States inherited conflicted territory from Mexico which was the home of both settlers and Apache tribes. Conflicts continued as new United States citizens came into traditional Apache lands to raise livestock and crops and to mine minerals.

The term Navajo Wars covers at least three distinct periods of conflict in the American West: the Navajo against the Spanish ; the Navajo against the Mexican government ; and the Navajo against the United States. These conflicts ranged from small-scale raiding to large expeditions mounted by governments into territory controlled by the Navajo. The Navajo Wars also encompass the widespread raiding that took place throughout the period; the Navajo raided other tribes and nearby settlements, who in return raided into Navajo territory, creating a cycle of raiding that perpetuated the conflict.

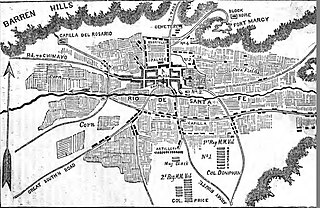

The Capture of Santa Fe, also known as the Battle of Santa Fe or the Battle of Cañoncito, took place near Santa Fe, New Mexico, the capital of the Mexican Province of New Mexico, during the Mexican–American War on 8 August through 14 August 1846. No shots were fired during the capturing of Santa Fe.

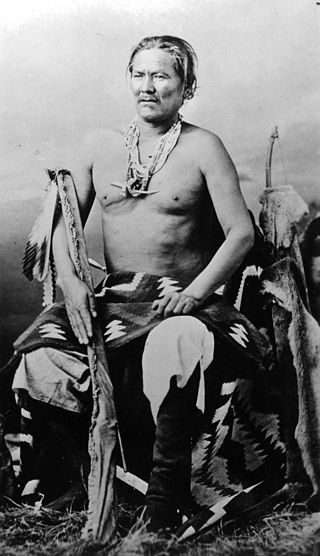

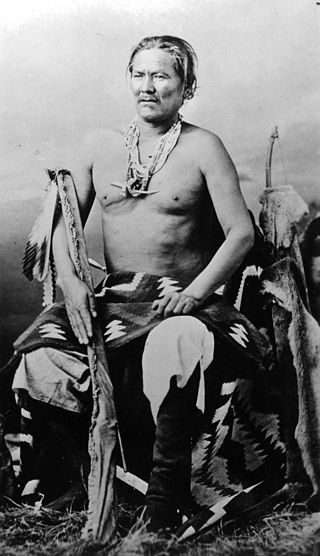

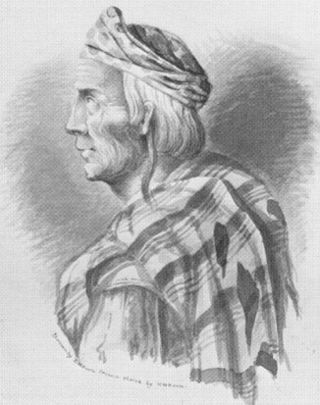

Chief Manuelito or Hastiin Chʼil Haajiní (1818–1893) was one of the principal headmen of the Diné people before, during and after the Long Walk Period. Manuelito is the diminutive form of the name Manuel, the Iberian variant of the name Immanuel; Manuelito roughly translates to Little Immanuel. He was born to the Bit'ahnii or ″Folded Arms People Clan″, near the Bears Ears in southeastern Utah about 1818. As many Navajo, he was known by different names depending upon context. He was Ashkii Diyinii, Dahaana Baadaané, Hastiin Ch'ilhaajinii and as Nabááh Jiłtʼaa to other Diné, and non-Navajo nicknamed him "Bullet Hole".

Fort Sumner was a military fort in New Mexico Territory charged with the internment of Navajo and Mescalero Apache populations from 1863 to 1868 at nearby Bosque Redondo.

The Navajos are a Native American people of the Southwestern United States.

Narbona or Hastiin Narbona was a Navajo chief who participated in the Navajo Wars. He was killed in a confrontation with U.S. soldiers on August 31, 1849.

The Navajo Scouts were part of the United States Army Indian Scouts between 1873 and 1895. Generally, the scouts were signed up at Fort Wingate for six month enlistments. In the period 1873 to 1885, there were usually ten to twenty-five scouts attached to units. United States Army records indicated that in the Geronimo Campaign of 1886, there were about 150 Navajo scouts, divided into three companies, who were part of the 5,000 man force General Nelson A. Miles put in the field. In 1891 they were enlisted for three years. The Navajos employed as scouts were merged into regular units of the army in 1895. At least one person served almost continuously for over twenty-five years.

Barboncito or Hastiin Dághaaʼ was a Navajo political and spiritual leader.

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the Intervención estadounidense en México, was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1845 American annexation of Texas, which Mexico still considered its territory. Mexico refused to recognize the Treaties of Velasco, because they were signed by President Antonio López de Santa Anna while he was captured by the Texas Army during the 1836 Texas Revolution. The Republic of Texas was de facto an independent country, but most of its Anglo-American citizens wanted to be annexed by the United States.

The Fourth Battle of Tucson was a raid during the lengthy wars between Spanish colonists in Arizona and its region and Apache Indians. At break of day, on March 21, 1784, a force of no more than 500 Apaches and Navajos attacked Spanish cavalry guards protecting a herd of livestock at the Presidio San Augustin del Tucson in southern Arizona.

The Battle of the Catalina River was a military engagement fought on March 21, 1784 during the Spanish conquest of the present day Arizona. The combatants were Apache and Navajo warriors, Spanish soldiers and Tucson militia.

José Antonio Vizcarra was a Mexican soldier who served as Governor of New Mexico from 1822 to 1823. While conducting an expedition against the Navajos in 1823, he was the first to record the ruins of Chaco Canyon.

Antonio Pascual Narbona was a Spanish soldier from Mobile (Mauvila in Spanish) now in Alabama, who fought native American people in the northern part of Mexico around the turn of the nineteenth century. He supported the independence of Mexico from Spain in 1821. He was Governor of the territory of Santa Fe de Nuevo México from September 1825 until 1827.

Williams v. Lee, 358 U.S. 217 (1959), was a landmark case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the State of Arizona does not have jurisdiction to try a civil case between a non-Indian doing business on a reservation with tribal members who reside on the reservation, the proper forum for such cases being the tribal court.

Blas de Hinojos was a military commander of New Mexico who was killed by a force of Navajo warriors led by Narbona in 1835.

Narbona Pass is a pass through the natural break between the Tunicha and Chuska Mountains, an elongated range on the Colorado Plateau on the Navajo Nation. A paved road, New Mexico Highway 134, crosses the range through Narbona Pass, connecting Sheep Springs to Crystal. Contrary to Navajo tradition of not naming monuments after people, the pass was given the name Narbona to celebrate his victory over an invading Mexican army that was sent to destroy the Navajo in 1835. Known in the Navajo Language as So Sila, the pass was lately named in English for Colonel John M. Washington in 1859. He was a New Mexico military governor who led an expedition into Navajo country in 1849 in which he was accused of walling up a Navajo Spring, and whose troops later shot Navajo leader Narbona.

The Treaty of Bosque Redondo was an agreement between the Navajo and the US Federal Government signed on June 1, 1868. It ended the Navajo Wars and allowed for the return of those held in internment camps at Fort Sumner following the Long Walk of 1864. The treaty effectively established the Navajo as a sovereign nation.

References

- Hughes, John, Doniphan's Expedition, U. P. James, 1847. Google books.

- Locke, Raymond, The Book of the Navajo, Mankind Publishing Company, 2001. ISBN 0-87687-500-2.

- Sides, Hampton, Blood and Thunder, Doubleday, 2006. ISBN 0-385-50777-1.

- Spicer, Edward, Cycles of Conquest, University of Arizona Press, 1962. ISBN 978-0-8165-0021-5.

- Sundberg, Lawrence, Dinétah: An Early History of the Navajo People, Sunstone Press, 1995.