Related Research Articles

In Japanese religion, Yahata formerly in Shinto and later commonly known as Hachiman is the syncretic divinity of archery and war, incorporating elements from both Shinto and Buddhism.

A Shinto shrine is a structure whose main purpose is to house ("enshrine") one or more kami, the deities of the Shinto religion.

The Japanese term shinbutsu bunri (神仏分離) indicates the separation of Shinto from Buddhism, introduced after the Meiji Restoration which separated Shinto kami from buddhas, and also Buddhist temples from Shinto shrines, which were originally amalgamated. It is a yojijukugo phrase.

The Shintōshū (神道集) is a Japanese setsuwa collection in ten volumes, believed to date from the Nanboku-chō period (1336–1392). It illustrates with tales about various shrines the Buddhist honji suijaku theory, according to which Japanese kami were simply local manifestations of the Indian gods of Buddhism. This theory, created and developed mostly by Tendai monks, was never systematized, but was nonetheless very pervasive and very influential. The book had thereafter great influence over literature and the arts.

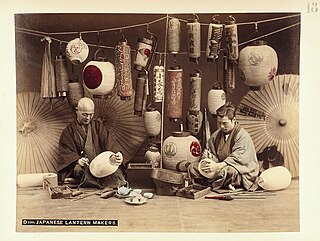

The traditional lighting equipment of Japan includes the andon (行灯), the bonbori (雪洞), the chōchin (提灯), and the tōrō (灯篭).

In Japanese, saisen is money offered to the gods or bodhisattvas. Commonly this money is put in a saisen box, a common item at Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples in Japan.

Himorogi in Shinto terminology are sacred spaces or altars used to worship. In their simplest form, they are square areas with green bamboo or sakaki at the corners without architecture. These in turn support sacred ropes (shimenawa) decorated with streamers called shide. A branch of sakaki or some other evergreen at the center acts as a yorishiro, a physical representation of the presence of the kami, a being which is in itself incorporeal.

Futarasan jinja (二荒山神社) is a Shinto shrine in the city of Nikkō, Tochigi Prefecture, Japan. It is also known as Nikkō Futarasan Shrine, to distinguish it from the Utsunomiya Futarayama Jinja, which shares the same kanji in its name. Both shrines claim the title of ichinomiya of the former Shimotsuke Province. The main festival of the shrine is held annually from April 13 to April 17.

Hōzen-ji (法善寺), is a Buddhist temple belonging to the Shingon school of Japanese Buddhism, located in the city of Minami-Alps, Yamanashi, Japan. Its main image is a statue of Amida Nyōrai.

The term honji suijaku or honchi suijaku (本地垂迹) in Japanese religious terminology refers to a theory widely accepted until the Meiji period according to which Indian Buddhist deities choose to appear in Japan as native kami to more easily convert and save the Japanese. The theory states that some kami are local manifestations of Buddhist deities. The two entities form an indivisible whole called gongen and in theory should have equal standing, but this was not always the case. In the early Nara period, for example, the honji was considered more important and only later did the two come to be regarded as equals. During the late Kamakura period it was proposed that the kami were the original deities and the buddhas their manifestations.

Shinto architecture is the architecture of Japanese Shinto shrines.

Usa Jingū (宇佐神宮), also known as Usa Hachimangū (宇佐八幡宮), is a Shinto shrine in the city of Usa in Ōita Prefecture in Japan. Emperor Ojin, who was deified as Hachiman-jin, is said to be enshrined in all the sites dedicated to him; and the first and earliest of these was at Usa in the early 8th century. The Usa Jingū has long been the recipient of Imperial patronage; and its prestige is considered second only to that of Ise.

A bodaiji in Japanese Buddhism is a temple which, generation after generation, takes care of a family's dead, giving them burial and performing ceremonies in their soul's favor. The name is derived from the term bodai (菩提), which originally meant just Buddhist enlightenment (satori), but which in Japan has also come to mean either the care of one's dead to ensure their welfare after death or happiness in the beyond itself. Several samurai families including the Tokugawa had their bodaiji built to order, while others followed the example of commoners and simply adopted an existing temple as family temple. Families may have more than one bodaiji. The Tokugawa clan, for example, had two, while the Ashikaga clan had several, both in the Kantō and the Kansai areas.

A sandō in Japanese architecture is the road approaching either a Shinto shrine or a Buddhist temple. Its point of origin is usually straddled in the first case by a Shinto torii, in the second by a Buddhist sanmon, gates which mark the beginning of the shrine's or temple territory. The word dō (道) can refer both to a path or road, and to the path of one's life's efforts. There can also be stone lanterns and other decorations at any point along its course.

Sessha and massha, also called eda-miya are small or miniature shrines entrusted to the care of a larger shrine, generally due to some deep connection with the enshrined kami.

The hachiman-zukuri (八幡造) is a traditional Japanese architectural style used at Hachiman shrines in which two parallel structures with gabled roofs are interconnected on the non-gabled side, forming one building which, when seen from the side, gives the impression of two. The front structure is called gaiden, the rear one naiden, and together they form the honden. The honden itself is surrounded by a cloister-like covered corridor called kairō' (回廊). Access is made possible by a gate called rōmon (楼門).

Kegare is the Japanese term for a state of pollution and defilement, important particularly in Shinto as a religious term. Typical causes of kegare are the contact with any form of death, childbirth, disease, and menstruation, and acts such as rape. In Shinto, kegare is a form of tsumi, which needs to be somehow remedied by the person responsible. This condition can be remedied through purification rites called misogi and harae. Kegare can have an adverse impact not only on the person directly affected, but also to the community they belong to.

In Japan, a chinjusha is a Shinto shrine which enshrines a tutelary kami; that is, a patron spirit that protects a given area, village, building or a Buddhist temple. The Imperial Palace has its own tutelary shrine dedicated to the 21 guardian gods of Ise Shrine. Tutelary shrines are usually very small, but there is a range in size, and the great Hiyoshi Taisha for example is Enryaku-ji's tutelary shrine. The tutelary shrine of a temple or the complex the two together form are sometimes called a temple-shrine. If a tutelary shrine is called chinju-dō, it is the tutelary shrine of a Buddhist temple. Even in that case, however, the shrine retains its distinctive architecture.

Until the Meiji period (1868–1912), the jingū-ji were places of worship composed of a Buddhist temple and a Shintō shrine, both dedicated to a local kami. These complexes were born when a temple was erected next to a shrine to help its kami with its karmic problems. At the time, kami were thought to be also subjected to karma, and therefore in need of a salvation only Buddhism could provide. Having first appeared during the Nara period (710–794), jingū-ji remained common for over a millennium until, with few exceptions, they were destroyed in compliance with the Kami and Buddhas Separation Act of 1868. Seiganto-ji is a Tendai temple part of the Kumano Sanzan Shinto shrine complex, and as such can be considered one of the few shrine-temples still extant.

Chinjugami is a god enshrined to protect a specific building or a certain area of land. Nowadays, it is often equated with Ujigami and Ubusunagami. A shrine that enshrines a guardian deity is called a Chinjusha.