Related Research Articles

Religion in the United States began with the religions and spiritual practices of Native Americans. Later, religion also played a role in the founding of some colonies, as many colonists, such as the Puritans, came to escape religious persecution. Historians debate how much influence religion, specifically Christianity and more specifically Protestantism, had on the American Revolution. Many of the Founding Fathers were active in a local Protestant church; some of them had deist sentiments, such as Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and George Washington. Some researchers and authors have referred to the United States as a "Protestant nation" or "founded on Protestant principles," specifically emphasizing its Calvinist heritage. Others stress the secular character of the American Revolution and note the secular character of the nation's founding documents.

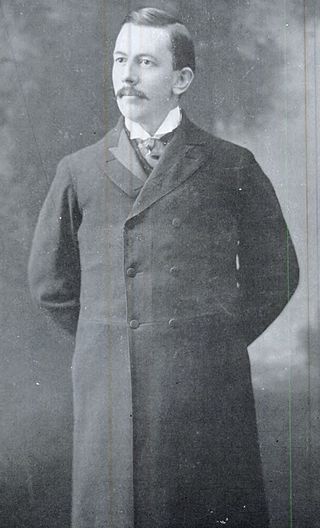

Columbus Delano was an American lawyer, rancher, banker, statesman, and a member of the prominent Delano family. Forced to live on his own at an early age, Delano struggled to become a self-made man. Delano was elected U.S. Congressman from Ohio, serving two full terms and one partial one. Prior to the American Civil War, Delano was a National Republican and then a Whig; as a Whig, he was identified with the faction of the party that opposed the spread of slavery into the Western territories. He became a Republican when the party was founded as the major anti-slavery party after the demise of the Whigs in the 1850s. During Reconstruction Delano advocated federal protection of African-Americans' civil rights, and argued that the former Confederate states should be administered by the federal government, but not as part of the United States until they met the requirements for readmission to the Union.

The Navajo or Diné, are a Native American people of the Southwestern United States.

The Pascua Yaqui Tribe of Arizona is a federally recognized tribe of Yaqui Native Americans in the state of Arizona.

The Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions is a Roman Catholic institution created in 1874 by J. Roosevelt Bayley, Archbishop of Baltimore, for the protection and promotion of Catholic mission interests among Native Americans in the United States. It is currently one of the three constituent members of the Black and Indian Mission Office.

Warren King Moorehead was an American archaeologist and writer who worked on excavating and surveying various Native American sites, including Fort Ancient. Moorehead the first curator of the Ohio Archaeological Society and was deemed the "Dean of American archaeology". He died on January 5, 1939, at the age of 72, and is buried in his hometown of Xenia, Ohio.

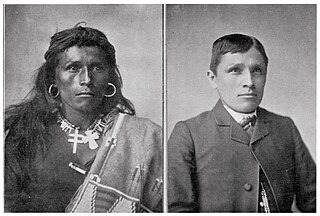

A series of efforts were made by the United States to assimilate Native Americans into mainstream European–American culture between the years of 1790 and 1920. George Washington and Henry Knox were first to propose, in the American context, the cultural assimilation of Native Americans. They formulated a policy to encourage the so-called "civilizing process". With increased waves of immigration from Europe, there was growing public support for education to encourage a standard set of cultural values and practices to be held in common by the majority of citizens. Education was viewed as the primary method in the acculturation process for minorities.

In United States history, an Indian agent was an individual authorized to interact with American Indian tribes on behalf of the U.S. government.

Native American civil rights are the civil rights of Native Americans in the United States. Native Americans are citizens of their respective Native nations as well as of the United States, and those nations are characterized under United States law as "domestic dependent nations", a special relationship that creates a tension between rights retained via tribal sovereignty and rights that individual Natives have as U.S. citizens. This status creates tension today but was far more extreme before Native people were uniformly granted U.S. citizenship in 1924. Assorted laws and policies of the United States government, some tracing to the pre-Revolutionary colonial period, denied basic human rights—particularly in the areas of cultural expression and travel—to indigenous people.

Native American self-determination refers to the social movements, legislation and beliefs by which the Native American tribes in the United States exercise self-governance and decision-making on issues that affect their own people.

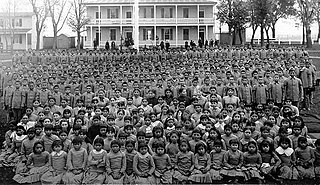

American Indian boarding schools, also known more recently as American Indian residential schools, were established in the United States from the mid-17th to the early 20th centuries with a primary objective of "civilizing" or assimilating Native American children and youth into Anglo-American culture. In the process, these schools denigrated Native American culture and made children give up their languages and religion. At the same time the schools provided a basic Western education. These boarding schools were first established by Christian missionaries of various denominations. The missionaries were often approved by the federal government to start both missions and schools on reservations, especially in the lightly populated areas of the West. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries especially, the government paid Church denominations to provide basic education to Native American children on reservations, and later established its own schools on reservations. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) also founded additional off-reservation boarding schools. Similarly to schools that taught speakers of immigrant languages, the curriculum was rooted in linguistic imperialism, the English only movement, and forced assimilation enforced by corporal punishment. These sometimes drew children from a variety of tribes. In addition, religious orders established off-reservation schools. In October 2024, U.S. President Joe Biden issued an official apology on behalf of the federal government for the abuse suffered in these boarding schools. In his apology, Biden discusses the history of boarding schools and blames the government for not apologizing sooner. He recognizes this kind of apology had never been issued before and addresses it to a crowd of Indigenous people.

The Indian Peace Commission was a group formed by an act of Congress on July 20, 1867 "to establish peace with certain hostile Indian tribes." It was composed of four civilians and three, later four, military leaders. Throughout 1867 and 1868, they negotiated with a number of tribes, including the Comanche, Kiowa, Arapaho, Kiowa-Apache, Cheyenne, Lakota, Navajo, Snake, Sioux, and Bannock. The treaties that resulted were designed to move the tribes to reservations, to "civilize" and assimilate these native peoples, and transition their societies from a nomadic to an agricultural existence.

The presidency of Ulysses S. Grant began on March 4, 1869, when Ulysses S. Grant was inaugurated as the 18th President of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1877. The Reconstruction era took place during Grant's two terms of office. The Ku Klux Klan caused widespread violence throughout the South against African Americans. By 1870, all former Confederate states had been readmitted into the United States and were represented in Congress; however, Democrats and former slave owners refused to accept that freedmen were citizens who were granted suffrage by the Fifteenth Amendment, which prompted Congress to pass three Force Acts to allow the federal government to intervene when states failed to protect former slaves' rights. Following an escalation of Klan violence in the late 1860s, Grant and his attorney general, Amos T. Akerman, head of the newly created Department of Justice, began a crackdown on Klan activity in the South, starting in South Carolina, where Grant sent federal troops to capture Klan members. This led the Klan to demobilize and helped ensure fair elections in 1872. He was succeeded by fellow Republican Rutherford B. Hayes, who won the 1876 presidential election.

The largest religion in the Nagaland state of India is Christianity. According to the 2011 census, the state's population was 1,978,502, out of which 87.93% are Christians. Along with Meghalaya, Arunachal Pradesh, and Mizoram, Nagaland is one of the four Christian-majority states in the country.

President Ulysses S. Grant sympathized with the plight of Native Americans and believed that the original occupants of the land were worthy of study. Grant's Inauguration Address set the tone for the Grant administration Native American Peace policy. The Board of Indian Commissioners was created to make reforms in Native policy and to ensure Native tribes received federal help. Grant lobbied the United States Congress to ensure that Native peoples would receive adequate funding. The hallmark of Grant's Peace policy was the incorporation of religious groups that served on Native agencies, which were dispersed throughout the United States.

There were ten American Indian Boarding Schools in Wisconsin that operated in the 19th and 20th centuries. The goal of the schools was to culturally assimilate Native Americans to European–American culture. This was often accomplished by force and abuse. The boarding schools were run by church, government, and private organizations.

Chamberlain Indian School was an American Indian boarding school in Chamberlain, South Dakota, located on the east bank of the Missouri River. It was among 25 off-reservation boarding schools opened by the federal government by 1898 in the plains region. It was administered by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and operated until 1908

Flandreau Indian School (FIS), previously Flandreau Indian Vocational High School, is a boarding school for Native American children in unincorporated Moody County, South Dakota, adjacent to Flandreau. It is operated by the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) and is off-reservation.

Tucson Indian school was founded by the United States federal government in 1888 to assimilate Native American children of the Akimel O'odham and Tohono Oʼodham tribes from the area around what is now Tucson, Arizona into mainstream American society. The school was created under federal acts with the goal of indoctrinating Native American children into Western colonial society by separating them from their communities' culture and reeducating them in boarding schools. The school closed in the 1950s.

The San Juan Episcopal Mission is a branch of the Episcopal Church in Navajoland Area Mission based in Farmington, New Mexico. Established in 1917, the mission serves sections of northwestern New Mexico, in particular the northern area of the Navajo Nation. What began as a small hospital and chapel functions today through three locations: All Saint's Episcopal Church in Farmington, St. Michael's Episcopal Church in Fruitland, and St. Luke's Episcopal Church in Bloomfield.

References

- ↑ United States Statutes at Large, XVI, 40.

- ↑ Thirty-Fourth Annual Report of the Board of Indian Commissioners, 1902 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1903), 22–23.

- ↑ Gates, Merrill Edwards (1885). "University of Oklahoma College of Law". digitialcommons.law.ou.edu. Retrieved 2020-05-28.

- ↑ Cartwright, Charles Edward (1979-03-06). "The University of Arizona University Libraries" (PDF). repository.arizona.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-09-04. Retrieved 2020-05-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ "Annual report of the Board of Indian Commissioners to the President of the United States. 4th (1872)". HathiTrust. Retrieved 2020-05-28.

- ↑ Francis Paul Prucha, American Indian Policy in Crisis, Christian Reformers and the Indian, 1865-1900, (2014) ISBN 0-8061-1279-4, 30–71.

- 1 2 "Board of Indian Commissioners". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2020-05-28.

- ↑ "Flora Warren Seymour". Simon & Schuster. Retrieved 2023-06-08.

- ↑ "American Women Historians, 1700s-1990s: A Biographical Dictionary". vdoc.pub. Retrieved 2023-06-08.