Current state of the law

Advances in the state of the art in medical science, including medical knowledge related to the viability of the fetus, and the ease with which the fetus can be observed in the womb as a living being, treated clinically as a human being, and (by certain stages) demonstrate neural and other processes considered as human, have led a number of jurisdictions – in particular in the United States – to supplant or abolish this common law principle. [8]

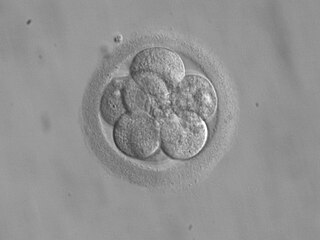

Examples of the evidence cited can be found within studies in ultrasonography, fetal heart monitoring, fetoscopy, and behavioral neuroscience. Studies in Neonatal perception suggest that the physiology required for consciousness does not exist prior to the 28th week, as this is when the thalamic afferents begin to enter the cerebral cortex. How long it takes for the requisite connection to be properly established is unknown at this time. Additionally, it is unclear whether the presence of certain hormones may keep the fetal brain sedated until birth. [9]

United Kingdom

The rule forms the foundation of UK law related to the fetus. In the case Attorney General's Reference No. 3 of 1994 Lord Mustill noted that the legal position of the unborn, and other pertinent rules related to transferred malice, were very strongly embedded in the structure of the law and had been considered relatively recently by the courts. [1] The Law Lords concurred that a fetus, although protected by the law in a number of ways, is legally not a separate person from its mother in English law. They described this as outdated and misconceived but legally established as a principle, adding that the fetus might be or not be a person for legal purposes, but could not in modern times be described as a part of its mother. The concept of transferred malice and general malice were also not without difficulties; these are the legal principles that say when a person engages in an unlawful act, they are responsible for its consequences, including (a) harm to others unintended to be harmed, and (b) types of harm they did not intend. [1] For example, the concept of transferred malice was applied where an assault caused a child to die not because it injured the child, but because it caused the child's premature birth. [10] It was also applied where manslaughter through a midwife's gross negligence caused a child to die before its complete birth. [11]

In Attorney General's Reference No. 3 of 1994 where a husband stabbed his pregnant wife, causing premature birth, and the baby died due to that premature birth, in English law no murder took place. "Until she had been born alive and acquired a separate existence she could not be the victim of homicide". The requirement for murder under English law, involving transfer of malice to a fetus, and then (notionally) from a fetus to the born child with legal personality, who died as a child at a later time despite never having suffered harm as a child with legal personality, nor even as a fetus having suffered any fatal wound (the injury sustained as a fetus was not a contributory cause), nor having malice deliberately directed at it, was described as legally "too far" to support a murder charge. [1] They noted that English law allowed for alternative remedies in some cases, specifically those based on "unlawful act" and "gross negligence" manslaughter and other offenses which do not require intent to harm the victim (manslaughter in English law is capable of a sentence up to and including life imprisonment): "Lord Hope has, however, ... [directed]... attention to the foreseeability on the part of the accused that his act would create a risk ... All that it [sic] is needed, once causation is established, is an act creating a risk to anyone; and such a risk is obviously established in the case of any violent assault ... The unlawful and dangerous act of B changed the maternal environment of the foetus in such a way that when born the child died when she would otherwise have lived. The requirements of causation and death were thus satisfied, and the four attributes of 'unlawful act' manslaughter were complete." [1]

In the same ruling, Lord Hope drew attention to the parallel case of Regina v. Mitchell ([1983] Q.B. 741) where a blow aimed at one person caused another to suffer harm leading to later death, and summarized the legal position of the 1994 case: "The intention which must be discovered is an intention to do an act which is unlawful and dangerous ... irrespective of who was the ultimate victim of it. The fact that the child whom the mother was carrying at the time was born alive and then died as a result of the stabbing is all that was needed for the offence of manslaughter when actus reus for that crime was completed by the child's death. The question, once all the other elements are satisfied, is simply one of causation. The defendant must accept all the consequences of his act, so long as the jury are satisfied that he did what he did intentionally, that what he did was unlawful and that, applying the correct test, it was also dangerous. The death of the child was unintentional, but the nature and quality of the act which caused it was such that it was criminal and therefore punishable. In my opinion that is sufficient for the offence of manslaughter. There is no need to look to the doctrine of transferred malice ... ." [1] In other cases where the fetus has not achieved independent existence, an act causing harm to an unborn child may be treated legally as harm to the mother herself. For example, in the case St George's Healthcare NHS Trust v S; R v Collins & Ors, ex parte S [12] it was held a trespass to the person when a hospital terminated a pregnancy involuntarily because the mother was diagnosed with severe pre-eclampsia. The court held that an unborn child's need for medical assistance does not prevail over the mother's autonomy and she is entitled to refuse consent to treatment, whether her own life or that of her unborn child depends on it.[ citation needed ]

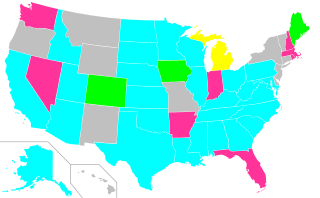

United States

The abolition of the rule has proceeded piecemeal, from case to case and from statute to statute, rather than wholesale. One such landmark case with respect to the rule was Commonwealth vs. Cass, in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, where the court held that the stillbirth of an eight-month-old fetus, whose mother had been injured by a motorist, constituted vehicular homicide. By a majority decision, the Supreme Court of Massachusetts held that a viable fetus constituted a "person" for the purposes of vehicular homicide law. In the opinion of the justices, "We think that the better rule is that infliction of perinatal injuries resulting in the death of a viable fetus, before or after it is born, is homicide." [13]

Several courts have held that it is not their function to revise statute law by abolishing the born alive rule, and have stated that such changes in the law should come from the legislature. In 1970 in Keeler v. Superior Court of Amador County, the California Supreme Court dismissed a murder indictment against a man who had caused the stillbirth of the child of his estranged pregnant wife, stating that "the courts cannot go so far as to create an offense by enlarging a statute, by inserting or deleting words, or by giving the terms used false or unusual meanings ... Whether to extend liability for murder in California is a determination solely within the province of the Legislature." [13] [14] Several legislatures have, as a consequence, revised their statutes to explicitly include deaths and injuries to fetuses in utero. The general policy has been that an attacker who causes the stillbirth of a fetus should be punished for the destruction of that fetus in the same way as an attacker who attacks a person and causes their death. Some legislatures have simply expanded their existing offences to explicitly include fetuses in utero. Others have created wholly new, and separate, offences. [13]