Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in Ghana face legal and societal challenges and discrimination not experienced by non-LGBT citizens.

Ritual servitude is a practice in Ghana, Togo, and Benin where traditional religious shrines take human beings, usually young virgin girls, in payment for services or in religious atonement for alleged misdeeds of a family member. In Ghana and in Togo, it is practiced by the Ewe people in the Volta region; in Benin, it is practiced by the Fon.

The continent of Africa is one of the regions most rife with contemporary slavery. Slavery in Africa has a long history, within Africa since before historical records, but intensifying with the trans-Saharan and Indian Ocean slave trade and again with the trans-Atlantic slave trade; the demand for slaves created an entire series of kingdoms which existed in a state of perpetual warfare in order to generate the prisoners of war necessary for the lucrative export of slaves. These patterns persisted into the colonial period during the late 19th and early 20th century. Although the colonial authorities attempted to suppress slavery from about 1900, this had very limited success, and after decolonization, slavery continues in many parts of Africa despite being technically illegal.

May Ayim is the pen name of May Opitz ; she was an Afro-German poet, educator, and activist. The child of a German dancer and Ghanaian medical student, she lived with a white German foster family when young. After reconnecting with her father and his family in Ghana, in 1992 she took his surname for a pen name.

The status of women in Ghana and their roles in Ghanaian society has changed over the past few decades. There has been a slow increase in the political participation of Ghanaian women throughout history. Women are given equal rights under the Constitution of Ghana, yet disparities in education, employment, and health for women remain prevalent. Additionally, women have much less access to resources than men in Ghana do. Ghanaian women in rural and urban areas face slightly different challenges. Throughout Ghana, female-headed households are increasing.

Every Child Ministries is a Christian charity and mission agency that works for African children. The charity is specially known for its advocacy on behalf of neglected, downtrodden, and marginalized groups of African children. It was first incorporated in the US in the state of Indiana in 1985, but is now incorporated and recognized as an NGO in all three of the African countries it ministers in.

Prostitution in Togo is legal and commonplace. Related activities such as solicitation, living off the earnings of prostitution or procuring are prohibited. Punishment is up to 10 years imprisonment if minors or violence is involved.

Yaba Badoe is a Ghanaian-British documentary filmmaker, journalist and author.

Elizabeth Akua Ohene is a Ghanaian journalist and a politician. She served as Minister of State for Tertiary Education in Ghana under President John Kufuor. She had previously served as the Editor of the Daily Graphic, the first woman in the role.

ZanetorAgyeman-Rawlings (Dr.) is Ghanaian medical doctor and politician who is the eldest daughter of the 1st President under the 4th Republic of Ghana Jerry Rawlings (1993–2001) and former first lady Nana Konadu Agyeman (1993–2001). She is a member of the Ghanaian parliament for the Klottey-Korle Constituency and a medical doctor and humanitarian.

Annie Ruth Jiagge, , also known as Annie Baëta Jiagge, was a Ghanaian lawyer, judge and women's rights activist. She was the first woman in Ghana and the Commonwealth of Nations to become a judge. She was a principal drafter of the Declaration on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women and a co-founder of the organisation that became Women's World Banking.

Nana Oforiatta Ayim is a Ghanaian writer, art historian and filmmaker.

Phyllis M. Christian is a Ghanaian lawyer and consultant who has been called "one of the most influential women in Ghana". A lawyer by training, she is also the founder, chief executive officer and managing consultant of ShawbellConsulting, based in Accra. Her grandfather George Alfred Grant, popularly known as Paa Grant, was one of the founding fathers of Ghana.

Pauline Miranda Clerk was a Ghanaian civil servant, diplomat and a presidential advisor.

Rose Akua Ampofo was a Ghanaian educator and gender advocate who became the first woman in Ghana to be ordained a Presbyterian minister. Between 1992 and 2002, she was the founding Director of the Presbyterian Women's Training Centre (PWTC) at Abokobi. From October 2002 until her death in March 2003, she was the Head of the Women and Gender Desk of Mission 21, formerly known as the Basel Mission in Basel, Switzerland.

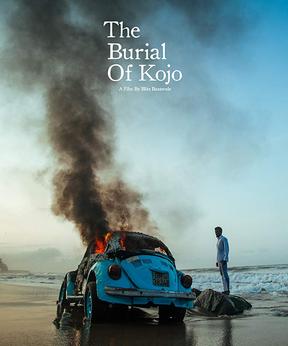

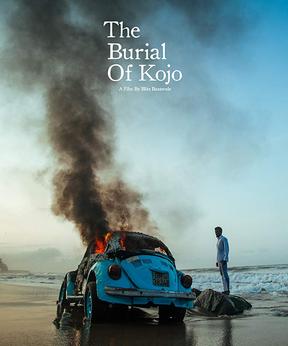

The Burial of Kojo is a 2018 Ghanaian drama film written, composed and directed by Blitz Bazawule. Produced by Bazawule, Ama K. Abebrese and Kwaku Obeng Boateng, it was filmed entirely in Ghana on a micro-budget, with local crew and several first-time actors. The film tells the story of Kojo, who is left to die in an abandoned gold mine, as his young daughter Esi travels through a spirit land to save him.

Juliana Dogbadzi is a Ghanaian human rights activist who has received the Reebok Human Rights Award.

Clara Amoateng Benson popularly known as Maame Serwaa is a young Ghanaian actress and brand ambassador. In April 2018, she was featured in BBC Africa’s documentary on the ThrivingGhanaian Movie Industry. She has also won several awards including Kumawood Best Actress of the Year 2015 and Ghana Tertiary Awards Best Actress of the Year 2018.

Hilary Amesika Gbedemah is Ghanaian lawyer and a women's right activist. She has been a member of the UN Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) since 2013, and she was the Committee's chairperson between 2019 and February 2021.

Witchcraft is deeply rooted in many African countries and communities in Sub-Saharan Africa. It has been specifically relevant in Ghana's culture, beliefs, and lifestyle and continues to shape lives daily. It has promoted tradition, fear, violence, and spiritual beliefs. The perceptions on witchcraft change from region to region within Ghana as they do in other countries in Africa, with the commonality that it is not something to take lightly, and the word spreading fast if there are rumours surrounding civilians practicing it. The actions taken by local citizens and the government towards witchcraft and violence related to it has also varied within regions in Ghana. Traditional African religions have depicted the universe as a multitude of spirits that are able to be used for either good or evil through religion.