Related Research Articles

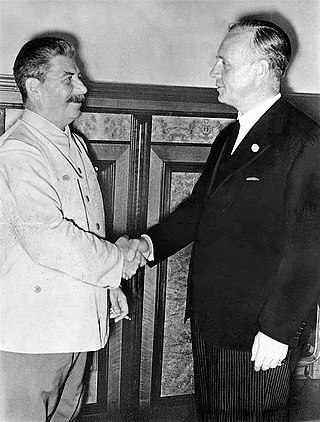

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, officially the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and also known as the Hitler–Stalin Pact and the Nazi–Soviet Pact, was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, with a secret protocol establishing Soviet and German spheres of influence across Northern Europe. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov and German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop.

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov was a Soviet politician, diplomat, and revolutionary who was a leading figure in the government of the Soviet Union from the 1920s to the 1950s, as one of Joseph Stalin's closest allies. Molotov served as Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars from 1930 to 1941, and as Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1939 to 1949 during the era of the Second World War, and again from 1953 to 1956.

The term "Soviet empire" collectively refers to the world's territories that the Soviet Union dominated politically, economically, and militarily. This phenomenon, particularly in the context of the Cold War, is also called Soviet imperialism by Sovietologists to describe the extent of the Soviet Union's hegemony over the Second World.

The history of the Soviet Union between 1927 and 1953, commonly referred to as the Stalin Era or Stalinist Era, covers the period in Soviet history from the establishment of Stalinism through victory in the Second World War and down to the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953. Stalin sought to destroy his enemies while transforming Soviet society with central planning, in particular through the forced collectivization of agriculture and rapid development of heavy industry. Stalin consolidated his power within the party and the state and fostered an extensive cult of personality. Soviet secret-police and the mass-mobilization of the Communist Party served as Stalin's major tools in molding Soviet society. Stalin's methods in achieving his goals, which included party purges, ethnic cleansings, political repression of the general population, and forced collectivization, led to millions of deaths: in Gulag labor camps and during famine.

"And you are lynching Negroes" is a catchphrase that describes or satirizes Soviet responses to US criticisms of Soviet human rights violations.

The Leningrad affair, or Leningrad case, was a series of criminal cases fabricated in the late 1940s–early 1950s by Joseph Stalin in order to accuse a number of prominent Leningrad based authority figures and members of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of treason and intention to create an anti-Soviet, Russian nationalist, organization based in the city. This happened in the aftermath of the Siege of Leningrad during the war, the victorious end of which led to the mayor, his deputies and others who kept Nazi German forces out of the city earning fame and strong support as heroes all over the USSR.

After the Russian Revolution, in which the Bolsheviks took over parts of the collapsing Russian Empire in 1918, they faced enormous odds against the German Empire and eventually negotiated terms to pull out of World War I. They then went to war against the White movement, pro-independence movements, rebellious peasants, former supporters, anarchists and foreign interventionists in the bitter civil war. They set up the Soviet Union in 1922 with Vladimir Lenin in charge. At first, it was treated as an unrecognized pariah state because of its repudiating of tsarist debts and threats to destroy capitalism at home and around the world. By 1922, Moscow had repudiated the goal of world revolution, and sought diplomatic recognition and friendly trade relations with the capitalist world, starting with Britain and Germany. Finally, in 1933, the United States gave recognition. Trade and technical help from Germany and the United States arrived in the late 1920s. After Lenin died in 1924, Joseph Stalin, became leader. He transformed the country in the 1930s into an industrial and military power. It strongly opposed Nazi Germany until August 1939, when it suddenly came to friendly terms with Berlin in the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. Moscow and Berlin by agreement invaded and partitioned Poland and the Baltic States. Stalin ignored repeated warnings that Hitler planned to invade. He was caught by surprise in June 1941 when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union. The Soviet forces nearly collapsed as the Germans reached the outskirts of Leningrad and Moscow. However, the Soviet Union proved strong enough to defeat Nazi Germany, with help from its key World War II allies, Britain and the United States. The Soviet army occupied most of Eastern Europe and increasingly controlled the governments.

The Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance and Mutual Assistance, or Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Alliance for short, was a bilateral treaty of alliance, collective security, aid and cooperation concluded between the People's Republic of China and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on February 14, 1950. It superseded the previous Sino-Soviet treaty signed by the Kuomintang government.

Censorship in the Soviet Union was pervasive and strictly enforced.

Sino-Soviet relations, or China–Soviet Union relations, refers to the diplomatic relationship between China and the various forms of Soviet Power which emerged from the Russian Revolution of 1917 to 1991, when the Soviet Union ceased to exist.

As soon as the term "Cold War" was popularized to refer to postwar tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union, interpreting the course and origins of the conflict became a source of heated controversy among historians, political scientists and journalists. In particular, historians have sharply disagreed as to who was responsible for the breakdown of Soviet Union–United States relations after the World War II and whether the conflict between the two superpowers was inevitable, or could have been avoided. Historians have also disagreed on what exactly the Cold War was, what the sources of the conflict were and how to disentangle patterns of action and reaction between the two sides. While the explanations of the origins of the conflict in academic discussions are complex and diverse, several general schools of thought on the subject can be identified. Historians commonly speak of three differing approaches to the study of the Cold War: "orthodox" accounts, "revisionism" and "post-revisionism". However, much of the historiography on the Cold War weaves together two or even all three of these broad categories and more recent scholars have tended to address issues that transcend the concerns of all three schools.

The Anglo-Soviet Treaty, formally the Twenty-Year Mutual Assistance Agreement Between the United Kingdom and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, established a military and political alliance between the Soviet Union and the British Empire.

After the Munich Agreement, the Soviet Union pursued a rapprochement with Nazi Germany. On 23 August 1939 the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact with Germany which included a secret protocol that divided Eastern Europe into German and Soviet "spheres of influence", anticipating potential "territorial and political rearrangements" of these countries. Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, starting World War II. The Soviets invaded eastern Poland on 17 September. Following the Winter War with Finland, the Soviets were ceded territories by Finland. This was followed by annexations of the Baltic states and parts of Romania.

The Turkish Straits crisis was a Cold War-era territorial conflict between the Soviet Union and Turkey. Turkey had remained officially neutral throughout most of the Second World War. After the war ended, Turkey was pressured by the Soviet government to institute joint military control of passage through Turkish Straits, which connected the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. When the Turkish government refused, tensions in the region rose, leading to a Soviet show of force and demands for territorial concessions along the Georgia–Turkey border.

I Chose Freedom: The Personal Political Life of a Soviet Official is a book by the Soviet Ukrainian defector Viktor Kravchenko. It was a bestseller in the United States and Europe. The book was written in 1946 and published in 1947. A review was published in The New York Times that year. I Chose Freedom depicts many episodes in Soviet history, including the Soviet famine of 1932–1933, the Gulag system, and the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact (1939).

This is a select bibliography of post-World War II English-language books and journal articles about Stalinism and the Stalinist era of Soviet history. Book entries have references to journal reviews about them when helpful and available. Additional bibliographies can be found in many of the book-length works listed below.

This is a select bibliography of English language books and journal articles about the Soviet Union during the Second World War, the period leading up to the war, and the immediate aftermath. For works on Stalinism and the history of the Soviet Union during the Stalin era, please see Bibliography of Stalinism and the Soviet Union. Book entries may have references to reviews published in English language academic journals or major newspapers when these could be considered helpful.

Kultura i zhizn was a cultural magazine which was published in the period 1946–1951 in Moscow, Soviet Union. It was one of the publications of the Central Committee of the Communist Party.

Shijie zhishi is a bimonthly semi-official foreign affairs magazine which has been in circulation since 1934 based in Beijing, China. From time to time the magazine was used as a propaganda publication by the state particularly during the Cold War. It is one of the long-running periodicals in China.

Foreign relations between France and the Soviet Union officially began on 28 October, 1924.

References

- ↑ John Jenks (2006). British Propaganda and News Media in the Cold War. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 22. doi:10.1515/9780748626755. ISBN 9780748626755.

- 1 2 Leonid T. Trofimov (2004). The Soviet media at the onset of the Cold War, 1945–1950 (PhD thesis). University of Illinois Chicago. pp. 65, 163. ISBN 978-0-496-87103-2. ProQuest 305075709.

- 1 2 Pauline Fairclough (August 2016). "Brothers in musical arms: the wartime correspondence of Dmitrii Shostakovich and Henry Wood". Russian Journal of Communication . 8 (3): 85–86. doi:10.1080/19409419.2016.1213219. hdl: 1983/373f474d-3a4b-4078-b82a-ee55df7d5a7f . S2CID 151854691.

- 1 2 Sarah Davies (2015). "The Soviet Union Encounters Anglia: Britain's Russian Magazine as a Medium for Cross-Border Communication". In Simo Mikkonen; Pia Koivunen (eds.). Beyond the divide: Entangled histories of Cold War Europe. New York; London: Berghahn Books. p. 218. ISBN 978-1-78238-866-1.

- 1 2 Vladimir O. Pechatnov (1998). "The Rise and Fall of Britansky Soyuznik: A Case Study in Soviet Response to British Propaganda of the Mid-1940s". The Historical Journal . 41 (1): 293–301. doi:10.1017/S0018246X97007577. JSTOR 2640154. S2CID 159914237.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Elena Goodwin (2019). Translating England into Russian: The Politics of Children's Literature in the Soviet Union and Modern Russia. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-1-350-13401-0.

- ↑ Pamela Davidson (2009). "Pasternak's letters to C.M. Bowra (1945–1956)". In Lazar Fleishman (ed.). The Life of Boris Pasternak's Doctor Zhivago. Oakland, CA: Berkeley Slavic Specialties. p. 85. ISBN 9781572010802.

- ↑ Alexey Tikhomirov (October 2015). "Book review". The Slavonic and East European Review . 93 (4): 779.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Vladimir O. Pechatnov (2001). "Exercise in Frustration: Soviet Foreign Propaganda in the Early Cold War, 1945-47". Cold War History . 1 (2): 19. doi:10.1080/713999921. S2CID 153657729.