Related Research Articles

The Picts were a group of peoples who lived in what is now northern and eastern Scotland during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and what their culture was like can be inferred from early medieval texts and Pictish stones. Their Latin name, Picti, appears in written records from the 3rd to the 10th century. Early medieval sources report the existence of a distinct Pictish language, which today is believed to have been an Insular Celtic language, closely related to the Brittonic spoken by the Britons who lived to the south.

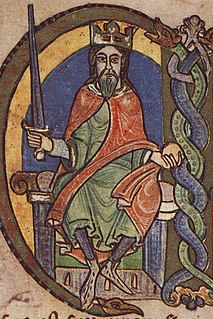

David I or Dauíd mac Maíl Choluim was a 12th-century ruler who was Prince of the Cumbrians from 1113 to 1124 and later King of Scotland from 1124 to 1153. The youngest son of Malcolm III and Margaret of Wessex, David spent most of his childhood in Scotland, but was exiled to England temporarily in 1093. Perhaps after 1100, he became a dependent at the court of King Henry I. There he was influenced by the Anglo-French culture of the court.

In early medieval Scotland, a mormaer was the Gaelic name for a regional or provincial ruler, theoretically second only to the King of Scots, and the senior of a Tòisich (chieftain). Mormaers were equivalent to English earls or Continental counts, and the term is often translated into English as 'earl'.

Donnchadh was a Gall-Gaidhil prince and Scottish magnate in what is now south-western Scotland, whose career stretched from the last quarter of the 12th century until his death in 1250. His father, Gille-Brighde of Galloway, and his uncle, Uhtred of Galloway, were the two rival sons of Fergus, Prince or Lord of Galloway. As a result of Gille-Brighde's conflict with Uhtred and the Scottish monarch William the Lion, Donnchadh became a hostage of King Henry II of England. He probably remained in England for almost a decade before returning north on the death of his father. Although denied succession to all the lands of Galloway, he was granted lordship over Carrick in the north.

Causantín or Constantine of Fife is the first man known for certain to have been Mormaer of Fife.

The Kingdom of Alba was the Kingdom of Scotland between the deaths of Donald II in 900 and of Alexander III in 1286, which then led indirectly to the Scottish Wars of Independence. The name is one of convenience, as throughout this period the elite and populace of the Kingdom were predominantly Pictish-Gaels or later Pictish-Gaels and Scoto-Norman, and differs markedly from the period of the House of Stuart, in which the elite of the kingdom were speakers of Middle English, which later evolved and came to be called Lowland Scots. There is no precise Gaelic equivalent for the English terminology "Kingdom of Alba", as the Gaelic term Rìoghachd na h-Alba means 'Kingdom of Scotland'. English-speaking scholars adapted the Gaelic name for Scotland to apply to a particular political period in Scottish history during the High Middle Ages.

Scottish Society in the High Middle Ages pertains to Scottish society roughly between 900 and 1286, a period roughly corresponding to the general historical era known as the High Middle Ages.

Scottish legal institutions in the High Middle Ages are, for the purposes of this article, the informal and formal systems which governed and helped to manage Scottish society between the years 900 and 1288, a period roughly corresponding with the general European era usually called the High Middle Ages. Scottish society in this period was predominantly Gaelic. Early Gaelic law tracts, first written down in the ninth century reveal a society highly concerned with kinship, status, honour and the regulation of blood feuds. The early Scottish lawman, or Breitheamh, became the Latin Judex; the great Breitheamh became the magnus Judex, which arguably developed into the office of Justiciar, an office which survives to this day in that of Lord Justice General. Scottish common law began to take shape at the end of the period, assimilating Gaelic and Celtic law with practices from Anglo-Norman England and the Continent.

Culture of Scotland in the High Middle Ages refers to the forms of cultural expression that come from Scotland in the High Medieval period which, for the purposes of this article, refers to the period between the death of Domnall II in 900, and the death of Alexander III in 1286. The unity of the period is suggested by the immense breaks which occur in Scottish history because of the Wars of Scottish Independence, the Stewart accession and transformations which occur in Scottish society in the fourteenth century and afterwards. The period differentiates itself because of the predominance of Gaelic culture, and, later in the medieval, Scoto-Norman French culture.

The High Middle Ages of Scotland encompass Scotland in the era between the death of Domnall II in 900 AD and the death of King Alexander III in 1286, which was an indirect cause of the Wars of Scottish Independence.

Andreas or Aindréas of Caithness is the first known bishop of Caithness and a source for the author of de Situ Albanie. Aindréas was a native Scot, and very likely came from a prominent family in Gowrie, or somewhere in this part of Scotland. He was a prominent landowner in Gowrie, Angus and Fife, and it is likely that he was a brother of one Eòghan "of Monorgan", another Gowrie landlord. At some stage in his career, he was a monk of Dunfermline Abbey, though it is not known if this was before or during his period as bishop of Caithness.

The Justiciar of Scotia was the most senior legal office in the High Medieval Kingdom of Scotland. Scotia in this context refers to Scotland to the north of the River Forth and River Clyde. The other Justiciar positions were the Justiciar of Lothian and the Justiciar of Galloway.

The Justiciar of Lothian was an important legal office in the High Medieval Kingdom of Scotland.

Walter FitzAlan was a twelfth-century English baron who became a Scottish magnate and Steward of Scotland. He was a younger son of Alan fitz Flaad and Avelina de Hesdin. In about 1136, Walter entered into the service of David I, King of Scotland. He became the king's dapifer or steward in about 1150, and served as such for three successive Scottish kings: David, Malcolm IV and William I. In time, the stewardship became hereditarily held by Walter's descendants.

St Serf's Inch or St Serf's Island is an island in Loch Leven, in south-eastern Perth and Kinross, Scotland. It was the home of a Culdee and then an Augustinian monastic community, St Serf's Inch Priory.

The Davidian Revolution is a name given by many scholars to the changes which took place in the Kingdom of Scotland during the reign of David I (1124–1153). These included his foundation of burghs, implementation of the ideals of Gregorian Reform, foundation of monasteries, Normanization of the Scottish government, and the introduction of feudalism through immigrant Norman and Anglo-Norman knights.

Gowrie is a region in central Scotland and one of the original provinces of the Kingdom of Alba. It covered the eastern part of what became Perthshire. It was located to the immediate east of Atholl, and originally included the area around Perth, though that was later detached as Perthia.

Gilchrist MacNachtan, son of Malcolm MacNachtan, was a thirteenth-century Scottish magnate.

The Provinces of Scotland were the primary subdivisions of the early Kingdom of Alba, first recorded in the 10th century and probably developing from earlier Pictish territories. Provinces were led by a mormaer, the leader of the most powerful provincial kin-group, and had military, fiscal and judicial functions. Their high degree of local autonomy made them important regional powerbases for competing claimants to the throne of Alba.

A toísech or toísech clainne was the head of a local kin-group in medieval Scotland. The word, meaning "first" or "leader" in Gaelic, is first attested in the property records written into the Book of Deer some time between the 1130s and the 1150s.

References

- 1 2 Grant 2000, p. 54.

- 1 2 Barrow 1966, p. 16.

- 1 2 Barrow 1966, p. 17.

- ↑ Broun 2015, p. 8.

- ↑ Taylor 2016, pp. 121–122.

- 1 2 Grant 2000, p. 55.

- 1 2 Barrow 1966, p. 18.

- ↑ Broun 2015, p. 55.

- ↑ Taylor 2016, p. 121.

- ↑ Taylor 2016, p. 131.

- ↑ Taylor 2016, p. 129.

- ↑ Taylor 2016, p. 233.