Related Research Articles

Hedley Norman Bull was Professor of International Relations at the Australian National University, the London School of Economics and the University of Oxford until his death from cancer in 1985. He was Montague Burton Professor of International Relations at Oxford from 1977 to 1985, and died there.

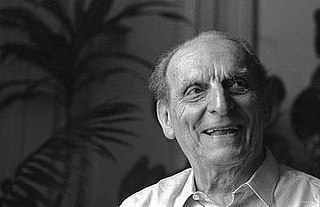

Norberto Bobbio was an Italian philosopher of law and political sciences and a historian of political thought. He also wrote regularly for the Turin-based daily La Stampa. Bobbio was a social liberal in the tradition of Piero Gobetti, Carlo Rosselli, Guido Calogero, and Aldo Capitini. He was also strongly influenced by Hans Kelsen and Vilfredo Pareto.

John Hugh "Adam" Watson was a British International relations theorist and researcher. Alongside Hedley Bull, Martin Wight, Herbert Butterfield, and others, he was one of the founding members of the English school of international relations theory.

Bruno Leoni was an Italian classical-liberal political philosopher and lawyer. Whilst the war kept Leoni away from teaching, in 1945 he became Full professor of Philosophy of Law. Leoni was also appointed Dean of the Department of Political Sciences at the University of Pavia from 1948 to 1960.

The English School of international relations theory maintains that there is a 'society of states' at the international level, despite the condition of anarchy. The English school stands for the conviction that ideas, rather than simply material capabilities, shape the conduct of international politics, and therefore deserve analysis and critique. In this sense it is similar to constructivism, though the English School has its roots more in world history, international law and political theory, and is more open to normative approaches than is generally the case with constructivism.

Costanzo Preve was an Italian philosopher and a political theoretician.

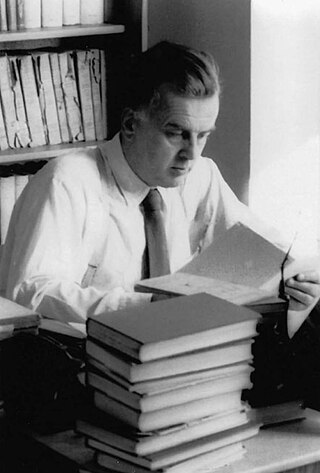

Robert James Martin Wight was one of the foremost British scholars of international relations in the twentieth century. He was the author of Power Politics, as well as the seminal essay "Why Is There No International Theory?". He was a teacher of some renown at both the London School of Economics and the University of Sussex, where he served as the founding Dean of European Studies.

Domestic analogy is an international affairs term coined by Professor Hedley Bull. Domestic analogy is the idea that states are like a "society of individuals". The analogy makes the presumption that relations between individuals and relations between states are the same. The domestic analogy is used when aggression is explained as the international equivalent of armed robbery or murder. A person can look at international affairs like a society of people, except there is no police, and every conflict threatens the structure as a whole with collapse.

Mario Ageno is considered one of Italy's most important biophysicists.

The Montague Burton Professorship of International Relations is a named chair at the University of Oxford and the London School of Economics, and a former chair at the University of Edinburgh. Created by the endowment of Montague Burton in UK universities, the Oxford chair was established in 1930 and is associated with a Fellowship of Balliol College, Oxford, while the chair at LSE was established in 1936.

Franco Fornari was an Italian psychiatrist, who was influenced by Melanie Klein and Wilfred Bion. He was a professor at the University of Milan and the University of Trento. From 1973 to 1978 he served as president of the Società Psicoanalitica Italiana.

Guido Zappa was an Italian mathematician and a noted group theorist: his other main research interests were geometry and also the history of mathematics. Zappa was particularly known for some examples of algebraic curves that strongly influenced the ideas of Francesco Severi.

Alberto Martinelli is a scholar of social sciences, President of the International Social Science Council, former 14th president of the International Sociological Association (1998-2002) and professor of Political Science and Sociology at the University of Milan.

Rodolfo Benini was an Italian statistician and demographer.

The Italian Society for Military History is a scientific society founded by Raimondo Luraghi, in Rome on 14 December 1984. Its aim is promoting studies in the field of military history and organizes meetings, seminars, and other events related to the society's aim. The society periodically issues studies, newsletters, and bulletins. Its primary aim is historical research in collaboration with organisations, societies, and students. It also grants scholarships for university degrees. Other initiatives related to the pursuit of the society's aim can be accomplished or sponsored by proposal by external subjects.

Power Politics is a book by international relations scholar Martin Wight, first published in 1946 as a 68-page essay. After 1959 Wight added twelve further chapters. Other works of Wight's were added by his former students, Hedley Bull and Carsten Holbraad, and a combined volume was published in 1978, six years after Wight's death. The book provides an overview of international politics featuring many elements of Realpolitik analysis.

Alberto Quadrio Curzio is an Italian economist. He is Professor Emeritus of Political Economy at Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milan, President Emeritus of the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei and President of the International Balzan Foundation "Prize".

Elena Brambilla was an Italian historian.

Pierpaolo Donati is an Italian sociologist and philosopher of social science, who is considered one of the main exponents of relational sociology and a prominent thinker in relational theory.

Paolo Valore is an Italian philosopher and academic who deals with metaphysics, general ontology and the ontological implications of formal theories. He is also interested in projects of artificial languages and auxiliary languages.

References

- Brunello Vigezzi, 'Il «British Committee on the Theory of International Politics» (1958-1985)', in Hedley Bull, Adam Watson (eds), L’espansione della societa’ internazionale (Milan: Jaca Book, 1994).

- Adam Watson, 'The British Committee for the Theory of International Politics: Some Historical Notes', 1998, University of Leeds .

- Olee Waever, 'Four Meanings of International Society', in B. Roberson (eds), International Society and the Development of International Relations Theory (London: Pinter, 1998) 93-108.

- Tim Dunne, Inventing International Society (London: St. Martin Press, 1998). [2]

- Alessandro Colombo, 'La società anarchica tra continuità e crisi. La scuola inglese e le istituzioni internazionali', Rassegna italiana di sociologia, 44:2, 2003, 237-255, available on-line, Jura Gentium - Rivista di filosofia del diritto internazionale e della politica globale .

- Brunello Vigezzi, The British Committee on the Theory of International Politics 1954-1985: The Rediscovery of History (Milan: Edizioni Unicopli, 2005). [3]

- Caroline Kennedy-Pipe e Nicholas Rengger, 'BISA at Thirty: Reflections on Three Decades of British International Relations Scholarship', Review of International Studies, 32:2006, pp. 665–676.

- Ian Hall, The International Thought of Martin Wight (New York, Palgrave, 2006).

- Michele Chiaruzzi, Politica di potenza nell'età del Leviatano. La teoria internazionale di Martin Wight (Bologna: Il Mulino, 2008).

- Silvia Maria Pizzetti (ed), La storia e la teoria della vita internazionale. Interpretazioni e discussioni (Milan: Edizioni Unicopli, 2009). With chapters by Alfredo Canavero, Alessandro Colombo, Michele Chiaruzzi, Elisabetta Brighi, Andrea Saccoman, Guido Formigoni, Giovanni Scirocco, Maria Matilde Benzoni, Giovanna Daverio Rocchi, Barbara Baldi, Elisa Orrù, Brunello Vigezzi.

- Luca G. Castellin, Società e anarchia. La "English School" e il pensiero politico internazionale (Roma: Carocci, 2018).