Historiography is the study of the methods used by historians in developing history as an academic discipline, and by extension, the term historiography is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians have studied that topic by using particular sources, techniques of research, and theoretical approaches to the interpretation of documentary sources. Scholars discuss historiography by topic—such as the historiography of the United Kingdom, of WWII, of the pre-Columbian Americas, of early Islam, and of China—and different approaches to the work and the genres of history, such as political history and social history. Beginning in the nineteenth century, the development of academic history produced a great corpus of historiographic literature. The extent to which historians are influenced by their own groups and loyalties—such as to their nation state—remains a debated question.

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the study of all history in time. Some historians are recognized by publications or training and experience. "Historian" became a professional occupation in the late nineteenth century as research universities were emerging in Germany and elsewhere.

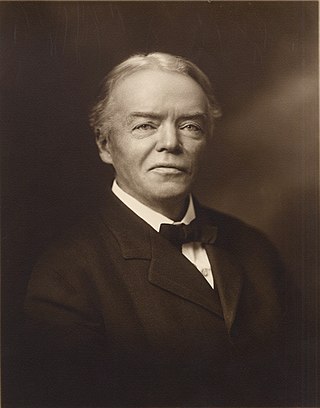

Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay, was a British historian, poet, and Whig politician, who served as the Secretary at War between 1839 and 1841, and as the Paymaster General between 1846 and 1848. He also played a substantial role in determining India's education policy.

Giambattista Vico was an Italian philosopher, rhetorician, historian, and jurist during the Italian Enlightenment. He criticized the expansion and development of modern rationalism, finding Cartesian analysis and other types of reductionism impractical to human life, and he was an apologist for classical antiquity and the Renaissance humanities, in addition to being the first expositor of the fundamentals of social science and of semiotics. He is recognised as one of the first Counter-Enlightenment figures in history.

Philosophy of history is the philosophical study of history and its discipline. The term was coined by the French philosopher Voltaire.

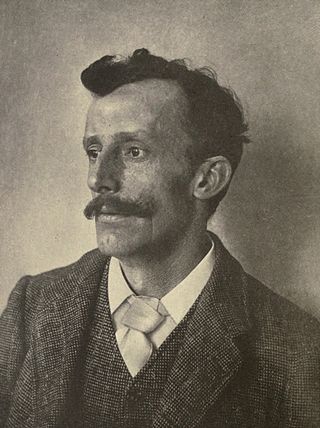

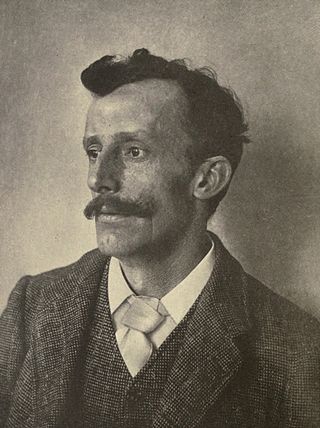

John Fiske was an American philosopher and historian. He was heavily influenced by Herbert Spencer and applied Spencer's concepts of evolution to his own writings on linguistics, philosophy, religion, and history.

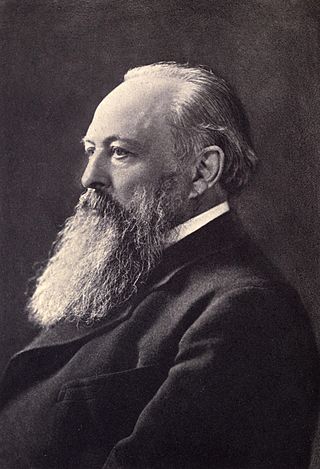

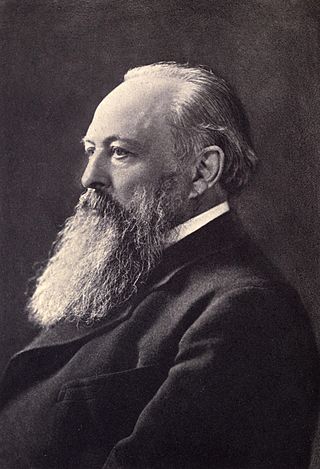

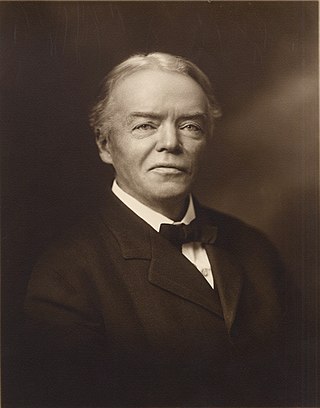

John Emerich Edward Dalberg-Acton, 1st Baron Acton, 13th Marquess of Groppoli,, better known as Lord Acton, was an English Catholic historian, politician, and writer. A strong advocate for individual liberty, Acton is best known for his timeless observation on the dangers of concentrated authority. In an 1887 letter to an Anglican bishop, he famously wrote, "Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely," underscoring his belief that unchecked power poses the greatest threat to human freedom. His works consistently emphasized the importance of limiting governmental and institutional power in favor of individual rights and personal liberty.

Frederic William Maitland was an English historian and jurist who is regarded as the modern father of English legal history. From 1884 until his death in 1906, he was reader in English law, then Downing Professor of the Laws of England at the University of Cambridge.

Whig history is an approach to historiography that presents history as a journey from an oppressive and benighted past to a "glorious present". The present described is generally one with modern forms of liberal democracy and constitutional monarchy: it was originally a term for the metanarratives praising Britain's adoption of constitutional monarchy and the historical development of the Westminster system. The term has also been applied widely in historical disciplines outside of British history to describe "any subjection of history to what is essentially a teleological view of the historical process". When the term is used in contexts other than British history, "whig history" (lowercase) is preferred.

Josiah Royce was an American Pragmatist and objective idealist philosopher and the founder of American idealism. His philosophical ideas included his joining of pragmatism and idealism, his philosophy of loyalty, and his defense of absolutism.

The American Enlightenment was a period of intellectual and philosophical fervor in the thirteen American colonies in the 18th to 19th century, which led to the American Revolution and the creation of the United States. The American Enlightenment was influenced by the 17th- and 18th-century Age of Enlightenment in Europe and distinctive American philosophy. According to James MacGregor Burns, the spirit of the American Enlightenment was to give Enlightenment ideals a practical, useful form in the life of the nation and its people.

Maurice John Cowling was a British historian. A fellow of Peterhouse, Cambridge, for most of his career, Cowling was a leading conservative exponent of the 'high politics' approach to political history.

Whiggism or Whiggery is a political philosophy that grew out of the Parliamentarian faction in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms (1639–1651). The Whigs advocated the supremacy of Parliament, and opposed granting freedom of religion, civil rights, or voting rights to anyone who worshipped outside of the Established Churches of the realm. The Whigs ultimately conceded strictly limited religious toleration for Protestant dissenters, while continuing the religious persecution and disenfranchisement of Roman Catholics. They were seeking to prevent a Catholic ascension to the English throne, especially that of James II or his descendants. The ideology is associated with early conservative liberalism.

Christopher Henry Dawson was an English Catholic historian, independent scholar, who wrote many books on cultural history and emphasized the necessity for Western culture to be in continuity with Christianity not to stagnate and deteriorate. Dawson has been called "the greatest English-speaking Catholic historian of the twentieth century" and was recognized as being able to expound his thought to "Catholic and Protestant, Christian and non-Christian."

Thomas Peter Ruffell Laslett was an English historian.

John Wyon Burrow, FBA was an English historian of intellectual history. His published works include assessments of the Whig interpretation of history and of historiography generally. According to The Independent: "John Burrow was one of the leading intellectual historians of his generation. His pioneering work marked the beginning of a more sophisticated approach to the history of the social sciences, one that did not treat the past as being of interest only in so far as it anticipated the present."

The historiography of the United Kingdom includes the historical and archival research and writing on the history of the United Kingdom, Great Britain, England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales. For studies of the overseas empire see historiography of the British Empire.

Constitutional history is the area of historical study covering both written constitutions and uncodified constitutions, and became an academic discipline during the 19th century. The Oxford Companion to Law (1980) defined it as the study of the "origins, evolution and historical development" of the constitution of a community.

Karl Wolfgang Schweizer is a historian specialising in eighteenth century European history.

The Structure of Politics at the Accession of George III is the title of a book written by Lewis Namier. At the time of its first publication in 1929, it caused a historiographical revolution in understanding the 18th century by challenging the Whig view of history that English politics had always been dominated by two parties.