The Golden Rule is the principle of treating others as one would want to be treated by them. It is sometimes called an ethics of reciprocity, meaning that you should reciprocate to others how you would like them to treat you. Various expressions of this rule can be found in the tenets of most religions and creeds through the ages.

The parable of the Good Samaritan is told by Jesus in the Gospel of Luke. It is about a traveler who is stripped of clothing, beaten, and left half dead alongside the road. A Jewish priest and then a Levite come by, both avoiding the man. A Samaritan happens upon him, and though Samaritans and Jews were generally antagonistic toward each other, helps him. Jesus tells the parable in response to a provocative question from a lawyer in the context of the Great Commandment: "And who is my neighbor?" The conclusion is that the neighbor figure in the parable is the one who shows mercy to their fellow man and/or woman.

Agape is "the highest form of love, charity" and "the love of God for [human beings] and of [human beings] for God". This is in contrast to philia, brotherly love, or philautia, self-love, as it embraces a profound sacrificial love that transcends and persists regardless of circumstance.

Psalm 89 is the 89th psalm of the Book of Psalms, beginning in English in the King James Version: "I will sing of the mercies of the LORD for ever". In the slightly different numbering system used in the Greek Septuagint and Latin Vulgate translations of the Bible, this psalm is Psalm 88. In Latin, it is known as "Misericordias Domini in aeternum cantabo". It is described as a maschil or "contemplation".

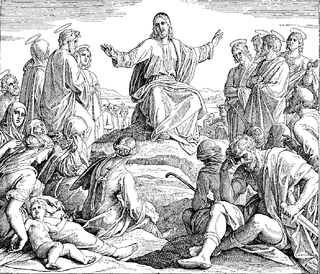

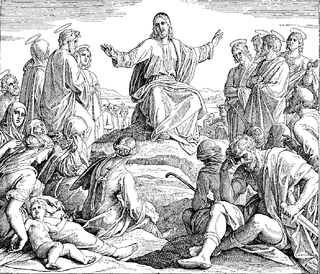

Matthew 5 is the fifth chapter of the Gospel of Matthew in the New Testament. It contains the first portion of the Sermon on the Mount, the other portions of which are contained in chapters 6 and 7. Portions are similar to the Sermon on the Plain in Luke 6, but much of the material is found only in Matthew. It is one of the most discussed and analyzed chapters of the New Testament. Warren Kissinger reports that among early Christians, no chapter was more often cited by early scholars. The same is true in modern scholarship.

Matthew 5:33 is the thirty-third verse of the fifth chapter of the Gospel of Matthew in the New Testament and is part of the Sermon on the Mount. This verse is the opening of the fourth antithesis, beginning the discussion of oaths.

The Ten Commandments, or the Decalogue, are religious and ethical directives, structured as a covenant document, that, according to the Hebrew Bible, are given by Yahweh to Moses. The text of the Ten Commandments was dynamic in ancient Israel and appears in three markedly distinct versions in the Bible: at Exodus 20:2–17, Deuteronomy 5:6–21, and the "Ritual Decalogue" of Exodus 34:11–26.

Matthew 5:40 is the fortieth verse of the fifth chapter of the Gospel of Matthew in the New Testament and is part of the Sermon on the Mount. This is the third verse of the antithesis on the commandment: "Eye for an eye".

Matthew 5:43 is the forty-third verse of the fifth chapter of the Gospel of Matthew in the New Testament and is part of the Sermon on the Mount. This verse is the opening of the final antithesis, that on the commandment to "Love thy neighbour as thyself".

Matthew 5:44, the forty-fourth verse in the fifth chapter of the Gospel of Matthew in the New Testament, also found in Luke 6:27–36, is part of the Sermon on the Mount. This is the second verse of the final antithesis, that on the commandment to "Love thy neighbour as thyself". In the chapter, Jesus refutes the teaching of some that one should "hate [one's] enemies".

The Great Commandment is a name used in the New Testament to describe the first of two commandments cited by Jesus in Matthew 22:35–40, Mark 12:28–34, and in answer to him in Luke 10:27a:

... and one of them, a lawyer, asked him a question to test him. "Teacher, which commandment in the law is the greatest?" He [Jesus] said to him, "'You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.' This is the greatest and first commandment. And the second is like it: 'You shall love your neighbor as yourself.' On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets."

Religious views on love vary widely between different religions.

The Second Commandment refers to and deals with the way Abrahamic worshippers of the true God worship. The second commandment's most obvious aspect governs the use of physical "helps" or "aids" in worshipping the spiritual God.

Judaism offers a variety of views regarding the love of God, love among human beings, and love for non-human animals. Love is a central value in Jewish ethics and Jewish theology.

"Thou shalt not take the name of the LORD thy God in vain" is the second or third of God's Ten Commandments to man in Judaism and Christianity.

"Thou shalt not commit adultery" is found in the Book of Exodus of the Hebrew Bible. It is considered the sixth commandment by Roman Catholic and Lutheran authorities, but the seventh by Jewish and most Protestant authorities. What constitutes adultery is not plainly defined in this passage of the Bible, and has been the subject of debate within Judaism and Christianity. The word fornication means illicit sex, prostitution, idolatry and lawlessness.

"I am the LORD thy God" is the opening phrase of the Ten Commandments, which are widely understood as moral imperatives by ancient legal historians and Jewish and Christian biblical scholars.

Psalm 50, a Psalm of Asaph, is the 50th psalm from the Book of Psalms in the Bible, beginning in English in the King James Version: "The mighty God, even the LORD, hath spoken, and called the earth from the rising of the sun unto the going down thereof." In the slightly different numbering system used in the Greek Septuagint and Latin Vulgate translations of the Bible, this psalm is Psalm 49. The opening words in Latin are Deus deorum, Dominus, locutus est / et vocavit terram a solis ortu usque ad occasum. The psalm is a prophetic imagining of God's judgment on the Israelites.

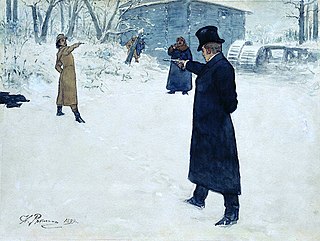

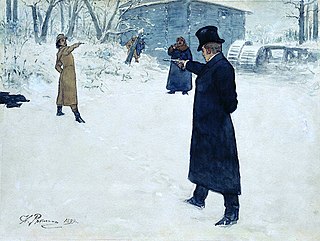

An enemy or a foe is an individual or a group that is considered as forcefully adverse or threatening. The concept of an enemy has been observed to be "basic for both individuals and communities". The term "enemy" serves the social function of designating a particular entity as a threat, thereby invoking an intense emotional response to that entity. The state of being or having an enemy is enmity, foehood or foeship.

The love of God is a prevalent concept both in the Old Testament and the New Testament. Love is a key attribute of God in Christianity, even if in the New Testament the expression "God is love" explicitly occurs only twice and in two not too distant verses: 1 John 4:8,16.