Bryant's Minstrels was a blackface minstrel troupe that performed in the mid-19th century, primarily in New York City. The troupe was led by the O'Neill brothers from upstate New York, who took the stage name Bryant. [1]

Bryant's Minstrels was a blackface minstrel troupe that performed in the mid-19th century, primarily in New York City. The troupe was led by the O'Neill brothers from upstate New York, who took the stage name Bryant. [1]

The eldest brother Jerry, a veteran of the Ethiopian Serenaders, Campbell's Minstrels, E.P. Christy's Minstrels and other troupes, sang and played tambourine and bones. Dan Bryant, who had toured with Losee's Minstrels, the Sable Harmonists and Campbell's Minstrels, sang and played banjo. Neil (Cornelius) Bryant played accordion and flutina. Other members, including English-born fiddler Phil Isaacs, rounded out the original roster. [2] All of the minstrels danced and acted in comedy segments, which were often improvised. [3] [4]

Bryant's Minstrels first performed on 23 February 1857 at Mechanics' Hall on Broadway. [5] The Bryants each brought with them the acts and songs they had learned and perfected while playing in other troupes. These older, proven pieces created a nostalgic format of primarily plantation-themed material that seemed to ignore contemporary discussion over abolition. Songs on the bill included Stephen Foster's "Gentle Annie" and the Christy Minstrels' "See, Sir, See" and "Down in Alabama". [1]

The Bryants proved a hit with audiences and critics alike. One reviewer wrote that "it is gratifying to find that we have yet among us those who will not suffer the original type of negro eccentricity to die out altogether. The connecting link . . . are [sic] the Bryant's Minstrels . . . and it is, therefore, to be hoped for that they will continue as they have begun, and stick to the 'old style' entertainment." [6] Over the next few months, they became one of New York's more popular acts. The Clipper wrote on 20 June that "The different bands of Minstrels, in this city, have experienced a wonderful falling off in patronage since the advent among us of the 'Bryants.'" [7] Another review spoke of "a combination of comical talent . . . never before witnessed in Ethiopian Minstrelsy . . . ." [8] Even a nationwide economic downturn in 1858 did not hurt their revenues. The Mechanics' Hall remained their primary venue until May 1866. [3]

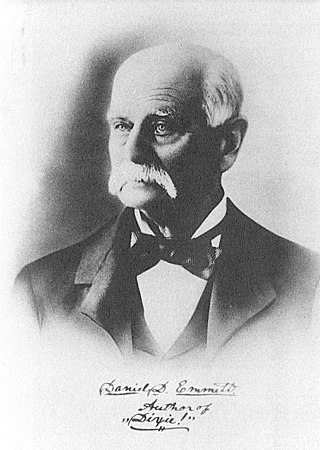

Over the troupe's life, members came and went. In October or November 1858, Dan Emmett joined as a primary songwriter for what would prove the most prolific period of his career. He also performed fiddle, banjo, drum, fife, and vocals. [9] The song "Dixie", usually attributed to him, was first performed on stage by the Bryants during an 1859 concert. [10] The final act of most minstrel shows of the time were blackface burlesques of mainstream theater, but "Dixie" and songs like it prompted an industry-wide revival of plantation-related material. Emmett's songs proliferated among rival companies. Emmett's influence also helped mature the walkaround from a simple dance to a complete song-and-dance routine. [11]

Next to Christy's Minstrels, the Bryants were the longest-lasting minstrel troupe to have formed before the Civil War. [12] Jerry Bryant died in 1861, but during the war, Bryant's Minstrels carried on, populating their shows with pro-Union songs such as "One Country and One Flag" and "Raw Recruits", as well as Irish characterizations and songs such as "Finnegan's Wake" and "Lanigan's Ball". [13]

In May 1866, Bryant's Minstrels left Mechanics' Hall, which burned down not long after, to minstrel promoter Charles "Charlie" White and went on a road trip to San Francisco. Dan Emmett left the troupe in July, though he occasionally continued to compose for them. [14] On their return to New York in 1868, the Bryants took over the Olympic Theatre in Tammany Hall on East 14th Street and later moved into their own "Opera House" on 23rd Street. [15]

The late 1860s and 1870s saw minstrel production grow increasingly elaborate and expensive and troupe sizes enlarge. [12] The Bryants stuck with their traditional formula and their popularity waned as a result. [3] Adding the African American dwarf Thomas Dilward to their ranks in the late 1860s (under the stage name "Japanese Tommy") did little to stem the tide. [16]

Dan Bryant died in his New York City home in 1875, but the troupe carried on for seven more years under the management of his surviving brother Neil. [17] [18]

The minstrel show, also called minstrelsy, was an American form of theater developed in the early 19th century. The shows were performed by mostly white actors wearing blackface make-up for the purpose of comically portraying racial stereotypes of African-Americans by playing the role of black minstrels. There were also some African-American performers and black-only minstrel groups that formed and toured. Minstrel shows stereotyped blacks as dim-witted, lazy, buffoonish, cowardly, superstitious, and happy-go-lucky. Each show consisted of comic skits, variety acts, dancing, and music performances that depicted people specifically of African descent.

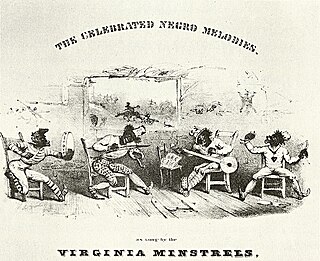

The Virginia Minstrels or Virginia Serenaders was a group of 19th-century American entertainers who helped invent the entertainment form known as the minstrel show. Led by Dan Emmett, the original lineup consisted of Emmett, Billy Whitlock, Dick Pelham, and Frank Brower.

Daniel Decatur Emmett was an American composer, entertainer, and founder of the first troupe of the blackface minstrel tradition, the Virginia Minstrels. He is most remembered as the composer of the song "Dixie".

Christy's Minstrels, sometimes referred to as the Christy Minstrels, were a blackface group formed by Edwin Pearce Christy, a well-known ballad singer, in 1843, in Buffalo, New York. They were instrumental in the solidification of the minstrel show into a fixed three-act form. The troupe also invented or popularized "the line", the structured grouping that constituted the first act of the standardized three-act minstrel show, with the interlocutor in the middle and "Mr. Tambo" and "Mr. Bones" on the ends.

"Dixie", also known as "Dixie's Land", "I Wish I Was in Dixie", and other titles, is a song about the Southern United States first made in 1859. It is one of the most distinctively Southern musical products of the 19th century. It was not a folk song at its creation, but it has since entered the American folk vernacular. The song likely cemented the word "Dixie" in the American vocabulary as a nickname for the Southern U.S.

"Old Dan Tucker," also known as "Ole Dan Tucker," "Dan Tucker," and other variants, is an American popular song. Its origins remain obscure; the tune may have come from oral tradition, and the words may have been written by songwriter and performer Dan Emmett. The blackface troupe the Virginia Minstrels popularized "Old Dan Tucker" in 1843, and it quickly became a minstrel hit, behind only "Miss Lucy Long" and "Mary Blane" in popularity during the antebellum period. "Old Dan Tucker" entered the folk vernacular around the same time. Today it is a bluegrass and country music standard. It is no. 390 in the Roud Folk Song Index.

The Ethiopian Serenaders was an American blackface minstrel troupe successful in the 1840s and 1850s. Through various line-ups they were managed and directed by James A. Dumbolton (c.1808–?), and are sometimes mentioned as the Boston Minstrels, Dumbolton Company or Dumbolton's Serenaders.

Buckley's Serenaders was a family troupe of English-born American blackface minstrels, established under that name in 1853 by James Buckley. They became one of the two most popular companies in the U.S. from the mid-1850s to the 1860s, the other being the Christy and Wood Minstrels.

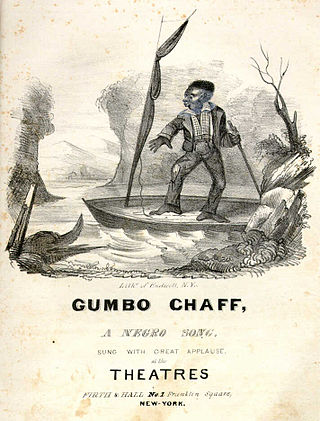

"Gumbo Chaff", also spelled "Gombo Chaff", is an American song, first performed in the early 1830s. It was part of the repertoire of early blackface performers, including Thomas D. Rice and George Washington Dixon.

"Clare de Kitchen" is an American song from the blackface minstrel tradition. It dates to 1832, when blackface performers such as George Nichols, Thomas D. Rice, and George Washington Dixon began to sing it. These performers and American writers such as T. Allston Brown traced the song's origins to black riverboatsmen. "Clare de Kitchen" became very popular, and performers sometimes sang the lyrics of "Blue Tail Fly" to its tune.

"De Wild Goose-Nation" is an American song composed by blackface minstrel performer Dan Emmett.

"I Ain't Got Time to Tarry", also known as "The Land of Freedom", is an American song written by blackface minstrel composer Dan Emmett. It premiered in a minstrel show performance by Bryant's Minstrels in late November 1858. The song was published in New York City in 1859.

Mechanics' Hall was a meeting hall and theatre seating 2,500 people located at 472 Broadway in New York City, United States. It had a brown façade. Built by the Mechanics' Society for their monthly meetings in 1847, it was also used for banquets, luncheons, and speeches held by other groups.

William M. Whitlock was an American blackface performer. He began his career in entertainment doing blackface banjo routines in circuses and dime shows, and by 1843 he was well known in New York City. He is best known for his role in forming the original minstrel show troupe, the Virginia Minstrels.

"Miss Lucy Long", also known as "Lucy Long" as well as by other variants, is an American song that was popularized in the blackface minstrel show.

Francis Marion Brower was an American blackface performer active in the mid-19th century. Brower began performing blackface song-and-dance acts in circuses and variety shows when he was 13. He eventually introduced the bones to his act, helping to popularize it as a blackface instrument. Brower teamed with various other performers, forming his longest association with banjoist Dan Emmett beginning in 1841. Brower earned a reputation as a gifted dancer. In 1842, Brower and Emmett moved to New York City. They were out of work by January 1843, when they teamed up with Billy Whitlock and Richard Pelham to form the Virginia Minstrels. The group was the first to perform a full minstrel show as a complete evening's entertainment. Brower pioneered the role of the endman.

"Mary Blane", also known as "Mary Blain" and other variants, is an American song that was popularized in the blackface minstrel show. Several different versions are known, but all feature a male protagonist singing of his lover Mary Blane, her abduction, and eventual death. "Mary Blane" was by far the most popular female captivity song in antebellum minstrelsy.

John Diamond, aka Jack or Johnny, was an Irish-American dancer and blackface minstrel performer. Diamond entered show business at age 17 and soon came to the attention of circus promoter P. T. Barnum. In less than a year, Diamond and Barnum had a falling-out, and Diamond left to perform with other blackface performers. Diamond's dance style merged elements of English, Irish, and African dance. For the most part, he performed in blackface and sang popular minstrel tunes or accompanied a singer or instrumentalist. Diamond's movements emphasized lower-body movements and rapid footwork with little movement above the waist.