David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party statesman and politician from Wales, he was known for leading the United Kingdom during the First World War, for social-reform policies, for his role in the Paris Peace Conference, and for negotiating the establishment of the Irish Free State. He was the last Liberal Party prime minister; the party fell into third-party status shortly after the end of his premiership.

Field Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener, was a senior British Army officer and colonial administrator. Kitchener came to prominence for his imperial campaigns, his involvement in the Second Boer War, and his central role in the early part of the First World War.

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith,, generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916. He was the last Liberal prime minister to command a majority government, and the most recent Liberal to have served as Leader of the Opposition. He played a major role in the design and passage of major liberal legislation and a reduction of the power of the House of Lords. In August 1914, Asquith took Great Britain and the British Empire into the First World War. During 1915, his government was vigorously attacked for a shortage of munitions and the failure of the Gallipoli Campaign. He formed a coalition government with other parties but failed to satisfy critics, was forced to resign in December 1916 and never regained power.

Field Marshal Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig, was a senior officer of the British Army. During the First World War he commanded the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front from late 1915 until the end of the war. He was commander during the Battle of the Somme, the Battle of Arras, the Third Battle of Ypres, the German Spring Offensive, and the Hundred Days Offensive.

Joseph Jacques Césaire Joffre was a French general who served as Commander-in-Chief of French forces on the Western Front from the start of World War I until the end of 1916. He is best known for regrouping the retreating allied armies to defeat the Germans at the strategically decisive First Battle of the Marne in September 1914.

Aristide Pierre Henri Briand was a French statesman who served eleven terms as Prime Minister of France during the French Third Republic. He is mainly remembered for his focus on international issues and reconciliation politics during the interwar period (1918–1939).

Field Marshal Sir Henry Hughes Wilson, 1st Baronet, was one of the most senior British Army staff officers of the First World War and was briefly an Irish unionist politician.

Jean Raphaël Adrien René Viviani was a French politician of the Third Republic, who served as Prime Minister for the first year of World War I. He was born in Sidi Bel Abbès, in French Algeria. In France he sought to protect the rights of socialists and trade union workers.

The year 1922 was a very important year in the history of modern Greece. It witnessed the fall of ideas birthed by Hellenism ever since the first days of its struggle for independence. The centenary of which had just been celebrated; more particularly of the idea of a greater Greece, which the name of Eleftherios Venizelos has been so closely associated ever since his first call to power in 1910. From a Balkan power of dominant magnitude, Greece was thrown back into the unenviable position, she occupied after the disastrous Greco-Turkish War of 1897.

The Curragh incident of 20 March 1914, sometimes known as the Curragh mutiny, occurred in the Curragh, County Kildare, Ireland. The Curragh Camp was then the main base for the British Army in Ireland, which at the time still formed part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Ireland was scheduled to receive a measure of devolved government, which included Ulster, later in the year. The incident is important in 20th-century Irish history, and is notable for being one of the few occasions since the English Civil War in which elements of the British military openly intervened in politics. It is widely thought of as a mutiny, though no orders actually given were disobeyed.

Reginald Baliol Brett, 2nd Viscount Esher, was an historian and Liberal politician in the United Kingdom, although his greatest influence over military and foreign affairs was as a courtier, member of public committees and behind-the-scenes "fixer", or rather éminence grise.

Field Marshal Sir William Robert Robertson, 1st Baronet, was a British Army officer who served as Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS) – the professional head of the British Army – from 1916 to 1918 during the First World War. As CIGS he was committed to a Western Front strategy focusing on Germany and was against what he saw as peripheral operations on other fronts. While CIGS, Robertson had increasingly poor relations with David Lloyd George, Secretary of State for War and then Prime Minister, and threatened resignation at Lloyd George's attempt to subordinate the British forces to the French Commander-in-Chief, Robert Nivelle. In 1917 Robertson supported the continuation of the Battle of Passchendaele at odds with Lloyd George's view that Britain's war effort ought to be focused on the other theatres until the arrival of sufficient US troops on the Western Front.

Joseph Simon Gallieni was a French soldier, active for most of his career as a military commander and administrator in the French colonies. Gallieni is infamous in Madagascar as the French military leader who exiled Queen Ranavalona III and abolished the 350-year-old monarchy on the island.

The Supreme War Council was a central command based in Versailles that coordinated the military strategy of the principal Allies of World War I: Britain, France, Italy, the US and Japan. It was founded in 1917 after the Russian revolution and with Russia's withdrawal as an ally imminent. The council served as a second source of advice for civilian leadership, a forum for preliminary discussions of potential armistice terms, later for peace treaty settlement conditions, and it was succeeded by the Conference of Ambassadors in 1920.

Maurice Paul Emmanuel Sarrail was a French general of the First World War. Sarrail's openly socialist political connections made him a rarity amongst the Catholics, conservatives and monarchists who dominated the French Army officer corps under the Third Republic before the war, and were the main reason why he was appointed to command at Salonika.

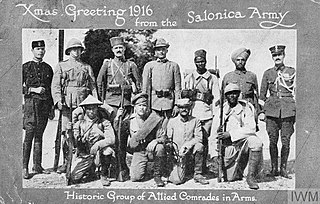

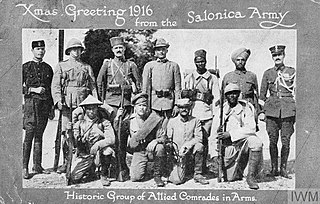

The Macedonian front, also known as the Salonica front, was a military theatre of World War I formed as a result of an attempt by the Allied Powers to aid Serbia, in the autumn of 1915, against the combined attack of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria. The expedition came too late and in insufficient force to prevent the fall of Serbia, and was complicated by the internal political crisis in Greece. Eventually, a stable front was established, running from the Albanian Adriatic coast to the Struma River, pitting a multinational Allied force against the Bulgarian Army, which was at various times bolstered with smaller units from the other Central Powers. The Macedonian front remained quite stable, despite local actions, until the great Allied offensive in September 1918, which resulted in the capitulation of Bulgaria and the liberation of Serbia.

The Noemvriana of December [O.S. November] 1916, or the Greek Vespers (after the Sicilian Vespers}, was a political dispute which led to an armed confrontation in Athens between the royalist government of Greece and the forces of the Allies over the issue of Greece's neutrality during World War I.

The Chantilly Conferences were a series of three conferences held between 1915 and 1916 by the Allied Powers of World War I. The conferences were named after Chantilly, France, where the meetings took place.

The Calais Conference was a 26 February 1917 meeting of politicians and generals from France and the United Kingdom. Ostensibly about railway logistics for the upcoming allied Spring offensive the majority of the conference was given over to a plan to bring British forces under overall French command. The British Prime Minister David Lloyd George was supportive of the proposal and arranged for the British war cabinet to approve it in advance of the conference, without the knowledge of senior British generals Douglas Haig and Sir William Robertson. The latter were surprised when the proposal was presented by French General Robert Nivelle at the conference. The next day the two generals met with Lloyd George and threatened their resignations rather than implement the proposal. This led to the significant watering-down of the plan with greater freedom given to British commanders. The conference caused mistrust between the British civil and military chiefs and set back the cause of a unified allied command until Spring 1918, when the successful German spring offensive rendered it essential.

The Calais Conference took place in the French city of Calais on 6 July 1915. It was intended to improve communication between the British and French governments on strategy for the First World War. It was the first face-to-face meeting between the British and French prime ministers H. H. Asquith and René Viviani. The meeting was poorly organised and no formal record was made of the decisions. The French thought that the British had committed to a major offensive on the Western Front while the British thought they had persuaded the French that the main British effort that year should be in the Gallipoli campaign. A meeting between military leaders at the conference led to a target of 70 divisions being set for the British Expeditionary Force, which would require the imposition of conscription.