Related Research Articles

Proposition 215, or the Compassionate Use Act of 1996, is a California law permitting the use of medical cannabis despite marijuana's lack of the normal Food and Drug Administration testing for safety and efficacy. It was enacted, on November 5, 1996, by means of the initiative process, and passed with 5,382,915 (55.6%) votes in favor and 4,301,960 (44.4%) against.

John Bernard Vasconcellos Jr. was an American politician from California and member of the Democratic Party. He represented Silicon Valley as a member of the California State Assembly for 30 years and a California State Senator for 8 years. His lifelong interest in psychology led to his advocacy of the self-esteem movement in California politics.

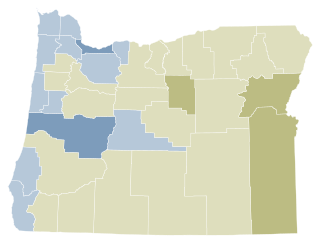

The Oregon Medical Marijuana Act, a law in the U.S. state of Oregon, was established by Oregon Ballot Measure 67 in 1998, passing with 54.6% support. It modified state law to allow the cultivation, possession, and use of marijuana by doctor recommendation for patients with certain medical conditions. The Act does not affect federal law, which still prohibits the cultivation and possession of marijuana.

In United States v. Oakland Cannabis Buyers' Cooperative, 532 U.S. 483 (2001), the United States Supreme Court rejected the common-law medical necessity defense to crimes enacted under the federal Controlled Substances Act of 1970, regardless of their legal status under the laws of states such as California that recognize a medical use for marijuana. Oakland Cannabis Buyers' Cooperative was represented by Gerald Uelmen.

Oaksterdam is a cultural district on the north end of Downtown Oakland, California, where medical cannabis is available for purchase in cafés, clubs, and patient dispensaries. Oaksterdam is located between downtown proper, the Lakeside, and the financial district. It is roughly bordered by 14th Street on the southwest, Harrison Street on the southeast, 19th Street on the northeast, and Telegraph Avenue on the northwest. The name is a portmanteau of "Oakland" and "Amsterdam," due to the Dutch city's cannabis coffee shops and the drug policy of the Netherlands.

Drug policy of California refers to the policy on various classes and kinds of drugs in the U.S. state of California. Cannabis possession has been legalized with the Adult Use of Marijuana Act, passed in November 2016, with recreational sales starting January of the next year. With respect to many controlled substances, terms such as illegal and prohibited do not include their authorized possession or sale as laid out by applicable laws.

Valerie Leveroni Corral is an American medical cannabis activist and writer. As a young adult she experienced a traumatic head injury that left her with a seizure disorder that antiepileptic medication could not ameliorate. Her experimental use of cannabis to treat her seizures led her to grow it on her property in Santa Cruz, California. In 1992, she was arrested for cannabis cultivation, becoming the first person in that state to argue the medical necessity defense. Following her success, she founded the Wo/Men's Alliance for Medical Marijuana (WAMM) and was a coauthor of Proposition 215, the first medical cannabis state ballot initiative to pass in the United States.

Cannabis in Oregon is legal for both medical and recreational use. In recent decades, the U.S. state of Oregon has had a number of legislative, legal, and cultural events surrounding use of cannabis. Oregon was the first state to decriminalize the possession of small amounts of cannabis, and among the first to authorize its use for medical purposes. An attempt to recriminalize possession of small amounts of cannabis was turned down by Oregon voters in 1997.

Cannabis in California has been legal for medical use since 1996, and for recreational use since late 2016. The state of California has been at the forefront of efforts to liberalize cannabis laws in the United States, beginning in 1972 with the nation's first ballot initiative attempting to legalize cannabis. Although it was unsuccessful, California would later become the first state to legalize medical cannabis through the Compassionate Use Act of 1996, which passed with 56% voter approval. In November 2016, California voters approved the Adult Use of Marijuana Act with 57% of the vote, which legalized the recreational use of cannabis.

The High TimesMedical Cannabis Cup is an annual event celebrating medical marijuana. The first Medical Cannabis Cup took place in San Francisco, California, on June 19–20, 2010.

A medical cannabis card or medical marijuana card is a state-issued identification card that enables a patient with a doctor's recommendation to obtain, possess, or cultivate cannabis for medicinal use despite marijuana's lack of the normal Food and Drug Administration testing for safety and efficacy. These cards are issued by a state or county in which medical cannabis is recognized. Typically a patient is required to pay a fee to the state in order to obtain a medical marijuana card. Sometimes it is alternatively referred to as medical marijuana identification (MMID), or medical marijuana (MMJ).

Gonzales v. Raich, 545 U.S. 1 (2005), was a decision by the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that, under the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution, Congress may criminalize the production and use of homegrown cannabis even if state law allows its use for medicinal purposes.

People v. Jovan Jackson, 210 Cal.App.4th 525 (2012) is a landmark decision by the Fourth Appellate District of California, which affirmed that persons that associate to collectively cultivate medical marijuana are entitled to a legal defense as provided by California Senate Bill 420. The decision has defined medical marijuana law in the state of California.

The Buffalo Cannabis Movement is an American grassroots organization based in Buffalo whose aim is to move public opinion sufficiently to achieve the legalization of non-medical marijuana in the United States so that the responsible use of cannabis by adults is no longer subject to penalty. BCM's mission aligns with NORML's mission of "support[ing] the removal of all criminal penalties for the private possession and responsible use of marijuana by adults, including the cultivation for personal use, and the casual nonprofit transfers of small amounts," and "support[ing] the development of a legally controlled market for cannabis."

Amendment 20 was an amendment to state statutes, submitted for referendum in the 2000 general elections in the U.S. state of Colorado. The amendment was adopted by 54% of participating voters. Under the law, patients may possess up to 2 ounces of medicinal marijuana and may cultivate no more than six marijuana plants at a time. Patients who are caught with more than this in their possession may argue "affirmative defense of medical necessity" but are not protected under state law with the rights of those who stay within the guidelines set forth by the state.[4]

The Adult Use of Marijuana Act (AUMA) was a 2016 voter initiative to legalize cannabis in California. The full name is the Control, Regulate and Tax Adult Use of Marijuana Act. The initiative passed with 57% voter approval and became law on November 9, 2016, leading to recreational cannabis sales in California by January 2018.

The Florida Medical Marijuana Legalization Initiative, also known as Amendment 2, was approved by voters in the Tuesday, November 8, 2016, general election in the State of Florida. The bill required a super-majority vote to pass, with at least 60% of voters voting for support of a state constitutional amendment. Florida already had a medical marijuana law in place, but only for those who are terminally ill and with less than a year left to live. The goal of Amendment 2 is to alleviate those suffering from these medical conditions: cancer, epilepsy, glaucoma, positive status for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Crohn's disease, Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, chronic nonmalignant pain caused by a qualifying medical condition or that originates from a qualified medical condition or other debilitating medical conditions comparable to those listed. Under Amendment 2, the medical marijuana will be given to the patient if the physician believes that the medical use of marijuana would likely outweigh the potential health risks for a patient. Smoking the medication was not allowed under a statute passed by the Florida State Legislature, however this ban was struck down by Leon County Circuit Court Judge Karen Gievers on May 25, 2018.

Cannabis in Hawaii is illegal for recreational use, but decriminalized for possession of three grams or less. Medical use was legalized through legislation passed in 2000, making Hawaii the first state to legalize medical use through state legislature rather than through ballot initiative.

Howard H. Shore is a Superior Court Judge of San Diego County, California for Department SD-15. Shore's remarks were widely covered by the media after he announced that the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution did not apply to chalk on the sidewalk, and he prohibited the defendant from mentioning terms like "First Amendment" or "free speech" during the trial.

Steve McWilliams was a medical marijuana activist from San Diego, California who protested the treatment of people under anti-cannabis laws. He committed suicide in 2005.

References

- ↑ "California's Medical Marijuana Laws Get Nod from Court". American Civil Liberties Union. 2006-11-16. Retrieved 2008-11-07.

- ↑ "An act to add Article 2.5 (commencing with Section 11362.7) to Chapter 6 of Division 10 of the Health and Safety Code, relating to controlled substances". State of California. October 12, 2003. Archived from the original on April 28, 2010. Retrieved April 15, 2010., §1(e)

- ↑ "An act to add Article 2.5 (commencing with Section 11362.7) to Chapter 6 of Division 10 of the Health and Safety Code, relating to controlled substances". State of California. October 12, 2003. Archived from the original on April 28, 2010. Retrieved April 15, 2010., California Legislative Counsel's digest

- ↑ "An act to add Article 2.5 (commencing with Section 11362.7) to Chapter 6 of Division 10 of the Health and Safety Code, relating to controlled substances". State of California. October 12, 2003. Archived from the original on April 28, 2010. Retrieved April 15, 2010., §1(a)(3)

- ↑ "An act to add Article 2.5 (commencing with Section 11362.7) to Chapter 6 of Division 10 of the Health and Safety Code, relating to controlled substances". State of California. October 12, 2003. Archived from the original on April 28, 2010. Retrieved April 15, 2010., §1(b), (c)

- 1 2 California Health and Safety Code, §11362.77

- ↑ California Health and Safety Code, §11362.775

- ↑ Savage, David G. (May 19, 2009). "Supreme Court upholds California medical pot law". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions for Applicants" (PDF). Santa Cruz County Health Services Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-06-15. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ "Medical Cannabis Voluntary Identification Card Program". San Francisco Department of Public Health. Retrieved 2010-09-15.

- ↑ The People v. Patrick K. Kelly, S164830 , pg. 50(Cal.2010).

- ↑ The People v. Patrick K. Kelly, S164830 , pg. 26(Cal.2010).

- ↑ The People v. Patrick K. Kelly, S164830 , pg. 49(Cal.2010).

- ↑ "City must relinquish seized medical pot". Bob Egelko. San Francisco Chronicle. 2 December 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ↑ "Garden Grove Decision" (PDF). Court of Appeal of the State of California. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-08-27. Retrieved 2010-09-15.

- ↑ Medical Marijuana Update: California

- ↑ People v. Jackson, (2012) 210 Cal.App.4th 1371