A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Aliceville is a city in Pickens County, Alabama, United States, located thirty-six miles west of Tuscaloosa. At the 2010 census its population was 2,486, down from 2,567 in 2000. Founded in the first decade of the 20th century and incorporated in 1907, the city has become notable for its World War II-era prisoner-of-war camp, Camp Aliceville. Since 1930, it has been the largest municipality in Pickens County.

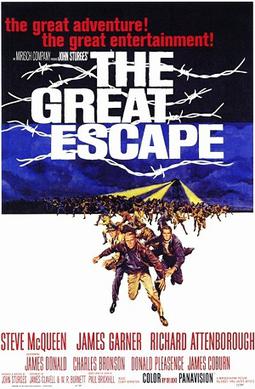

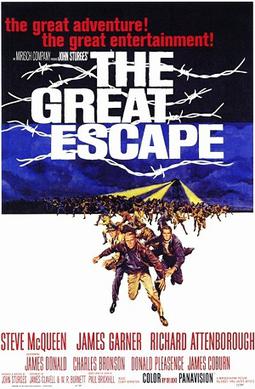

The Great Escape is a 1963 American epic war suspense adventure film starring Steve McQueen, James Garner and Richard Attenborough and featuring James Donald, Charles Bronson, Donald Pleasence, James Coburn, Hannes Messemer, David McCallum, Gordon Jackson, John Leyton and Angus Lennie. It was filmed in Panavision, and its musical score was composed by Elmer Bernstein.

A prisoner-of-war camp is a site for the containment of enemy fighters captured by a belligerent power in time of war.

The Atlit detainee camp was a concentration camp established by the authorities of Mandatory Palestine in the late 1930s on what is now the Israeli coastal plain, 20 kilometres (12 mi) south of Haifa. Under British rule, it was primarily used to hold Jews and Arabs who were in administrative detention; it largely held Jewish immigrants who did not possess official entry permits. Tens of thousands of Jewish refugees were interned at the camp, which was surrounded by barbed wire and watchtowers.

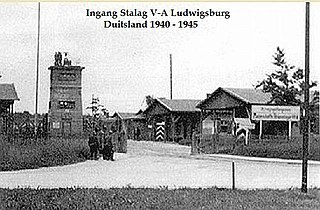

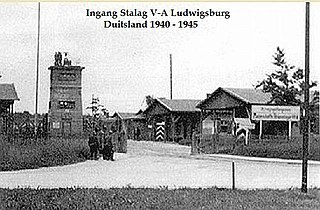

In Germany, stalag was a term used for prisoner-of-war camps. Stalag is a contraction of "Stammlager", itself short for Kriegsgefangenen-Mannschaftsstammlager, a literal translation of which is "War-prisoner" "enlisted" "main camp". Therefore, technically "stalag" simply means "main camp".

A civilian internee is a civilian detained by a party to a war for security reasons. Internees are usually forced to reside in internment camps. Historical examples include Japanese American internment and internment of German Americans in the United States during World War II. Japan interned 130,000 Dutch, British, and American civilians in Asia during World War II.

Oflag X-B was a World War II German prisoner-of-war camp for officers (Offizierlager) located in Nienburg/Weser, Lower Saxony, in north-western Germany. Adjacent to it was the enlisted men's camp (Stammlager) Stalag X-C.

Stalag V-A was a German World War II prisoner-of-war camp (Stammlager) located on the southern outskirts of Ludwigsburg, Germany. It housed Allied POWs of various nationalities, including Poles, Belgians, Dutchmen, Frenchmen, Britons, Soviets, Italians and Americans.

Oflag XXI-C was a German Army World War II prisoner-of-war camp for officers (Offizierlager) located in Ostrzeszów in German-occupied Poland. It held mostly Norwegian officers arrested in 1942 and 1943, but also Dutch, Italian, Serbian and Soviet POWs. Originally most Norwegian soldiers and officers had been released after the end of the Norwegian campaign, but as resistance activities increased, the officers were rearrested and sent to POW camps.

Stephen Fleck was a professor in the psychiatry, epidemiology and public health departments at the Yale University School of Medicine from 1953 to 1983 and professor emeritus from 1983 until his death.

Wilhelm Reinhold Johannes Kunze was a German World War II prisoner of war (POW) held at Camp Tonkawa, Oklahoma. He was a Gefreiter in the Afrika Korps. Following a trial before a kangaroo court on November 4, 1943, he was beaten to death by fellow POWs based on allegations of treason and spying for the Americans. The unmasking of Kunze happened by accident; he had been in the habit of passing notes to the American doctor at the camp during sick call. These notes contained useful information regarding the activities of various POWs in the camp, some of whom were loyal Nazis. One day a new American doctor was on duty who did not know about Kunze's role as spy and who could not speak German. When Kunze handed over his note, the American doctor accidentally blew Kunze's cover by sending it back via another POW, who read the incriminating note and quickly realised that Kunze was a spy. News of this discovery spread quickly and soon afterwards Kunze was killed inside the camp by his fellow POWs. He is buried in the Fort Reno prisoner of war cemetery.

Camp Ruston was one of the largest prisoner-of-war camps in the United States during World War II, with 4,315 prisoners at its peak in October 1943. Camp Ruston served as the "base camp" and had 8 smaller work branch camps associated to it. Camp Ruston included three large, separated compounds for POWs, a full, modern hospital compound, and a compound for the American personnel. One of the POW compounds, located in the far northwestern part of the camp was designated for POW officers. The officer's compound's barracks were constructed to house a lesser number of POWs affording more privacy and room for the officers. The enlisted men's barracks were designed to house a maximum of 50 POWs in two rows of bunks that ran along each side. POW latrines were separate buildings located at the end of each compound.

The use of slave and forced labour in Nazi Germany and throughout German-occupied Europe during World War II took place on an unprecedented scale. It was a vital part of the German economic exploitation of conquered territories. It also contributed to the mass extermination of populations in occupied Europe. The Germans abducted approximately 12 million people from almost twenty European countries; about two thirds came from Central Europe and Eastern Europe. Many workers died as a result of their living conditions – extreme mistreatment, severe malnutrition, and worse tortures were the main causes of death. Many more became civilian casualties from enemy (Allied) bombing and shelling of their workplaces throughout the war. At its peak the forced labourers constituted 20% of the German work force. Counting deaths and turnover, about 15 million men and women were forced labourers at one point during the war.

Members of the German military were interned as prisoners of war in the United States during World War I and World War II. In all, 425,000 German prisoners lived in 700 camps throughout the United States during World War II.

Oflag II-A was a German World War II prisoner-of-war camp located in the town of Prenzlau, Brandenburg, 93 kilometres (58 mi) north of Berlin. It housed mainly Polish and Belgian officers.

Whitewater was a labour camp for German prisoners-of-war in Riding Mountain National Park, Manitoba. Operating from 1943 to 1945, the camp was built on the northeast shore of Whitewater Lake, approximately 300 kilometres (190 mi) north-west of Winnipeg. The camp consisted of fifteen buildings and housed 440 to 450 prisoners of war.

Camp Opelika was a World War II era prisoner of war (POW) camp in Opelika, Alabama. Its construction began in September 1942 and it shut down in September 1945. The first prisoners, captured by the British, were part of General Erwin Rommel's feared Africa Corps. It held approximately 3,000 German prisoners at any one time.