Related Research Articles

The Divine Comedy is an Italian narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun c. 1308 and completed around 1321, shortly before the author's death. It is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature and one of the greatest works of Western literature. The poem's imaginative vision of the afterlife is representative of the medieval worldview as it existed in the Western Church by the 14th century. It helped establish the Tuscan language, in which it is written, as the standardized Italian language. It is divided into three parts: Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso.

A troubadour was a composer and performer of Old Occitan lyric poetry during the High Middle Ages (1100–1350). Since the word troubadour is etymologically masculine, a female equivalent is usually called a trobairitz.

Arnaut Daniel was an Occitan troubadour of the 12th century, praised by Dante as "the best smith" and called a "grand master of love" by Petrarch. In the 20th century he was lauded by Ezra Pound in The Spirit of Romance (1910) as the greatest poet to have ever lived.

Occitan literature is a body of texts written in Occitan, mostly in the south of France. It was the first literature in a Romance language and inspired the rise of vernacular literature throughout medieval Europe. Occitan literature's Golden Age was in the 12th century, when a rich and complex body of lyrical poetry was produced by troubadours writing in Old Occitan, which still survives to this day. Although Catalan is considered by some a variety of Occitan, this article will not deal with Catalan literature, which started diverging from its Southern French counterpart in the late 13th century.

Bertran de Born was a baron from the Limousin in France, and one of the major Occitan troubadours of the 12th-13th century. He composed love songs (cansos) but was better known for his political songs (sirventes). He was involved in revolts against Richard I and then Phillip II. He married twice and had five children. In his final years, he became a monk.

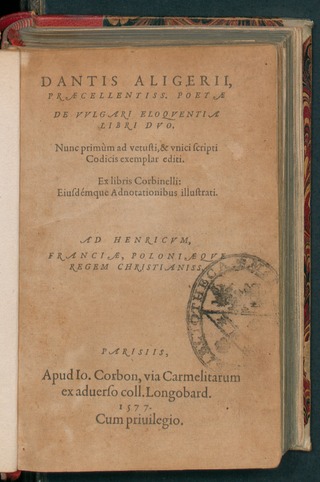

De vulgari eloquentia is the title of a Latin essay by Dante Alighieri. Although meant to consist of four books, it abruptly terminates in the middle of the second book. It was probably composed shortly after Dante went into exile, circa 1302–1305.

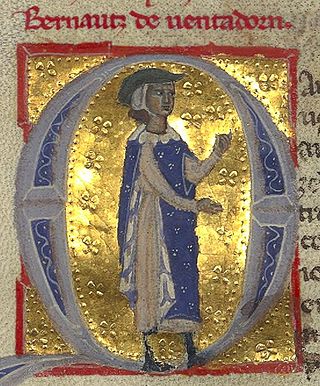

Bernart de Ventadorn was a French poet-composer troubadour of the classical age of troubadour poetry. Generally regarded as the most important troubadour in both poetry and music, his 18 extant melodies of 45 known poems in total is the most to survive from any 12th-century troubadour. He is remembered for his mastery as well as popularization of the trobar leu style, and for his prolific cançons, which helped define the genre and establish the "classical" form of courtly love poetry, to be imitated and reproduced throughout the remaining century and a half of troubadour activity.

The trobairitz were Occitan female troubadours of the 12th and 13th centuries, active from around 1170 to approximately 1260. Trobairitz is both singular and plural.

Maria de Ventadorn was a patron of troubadour poetry at the end of the 12th century.

Cunizza da Romano was an Italian noblewoman and a member of the da Romano dynasty, one of the most prominent families in northeastern Italy, Cunizza's marriages and liaisons, most notably with troubadour Sordello da Goito, are widely documented. Cunizza also appears as a character in a number of works of literature, such as Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy.

The canso or canson or canzo was a song style used by the troubadours. It was, by far, the most common genre used, especially by early troubadours, and only in the second half of the 13th century was its dominance challenged by a growing number of poets writing coblas esparsas.

Raimon Vidal de Bezaudu(n) (Catalan: Ramon Vidal de Besalú) (flourished early 13th century) was a Catalan troubadour from Besalú. He is notable for authoring the first tract in a Romance language (Occitan) on the subject of grammar and poetry, the Razós de trobar (c. 1210), a title which translates as "Reasons (or Guidelines) of troubadour composition". He began his career as a joglar and he spent his formative years at the court of Hug de Mataplana, which he often recalls fondly in his poems and songs.

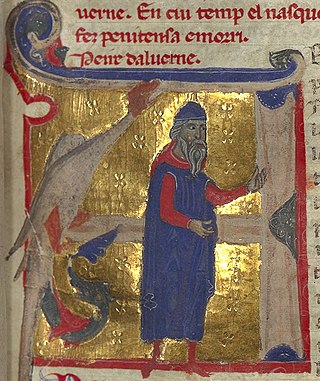

Peire d'Alvernhe or d'Alvernha was an Auvergnat troubadour with twenty-one or twenty-four surviving works. He composed in an "esoteric" and "formally complex" style known as the trobar clus. He stands out as the earliest troubadour mentioned by name in Dante's Divine Comedy.

Uc de Saint Circ or Hugues (Hugh) de Saint Circq was a troubadour from Quercy. Uc is perhaps most significant to modern historians as the probable author of several vidas and razos of other troubadours, though only one of Bernart de Ventadorn exists under his name. Forty-four of his songs, including fifteen cansos and only three canso melodies, have survived, along with a didactic manual entitled Ensenhamen d'onor. According to William E. Burgwinkle, as "poet, biographer, literary historian, and mythographer, Uc must be accorded his rightful place as the 'inventor' (trobador) of 'troubadour poetry' and the idealogical trappings with which it came to be associated."

In Old Occitan literature, a tornada refers to a final, shorter stanza that appears in lyric poetry and serves a variety of purposes within several poetic forms. The word tornada derives from the Old Occitan in which it is the feminine form of tornat, a past participle of the verb tornar. It is derived from the Latin verb tornare.

Alegret was a Gascon troubadour, one of the earliest lyric satirists in the Occitan tongue, and a contemporary of Marcabru. Only one sirventes and one canso survive of his poems. Nonetheless, his reputation was high enough that he found his way into the poetry of Bernart de Ventadorn and Raimbaut d'Aurenga. The work of Alegret is also intertextually and stylistically related to that of Peire d'Alvernhe.

Dante da Maiano was a late thirteenth-century poet who composed mainly sonnets in Italian and Occitan. He was an older contemporary of Dante Alighieri and active in Florence.

Paradiso is the third and final part of Dante's Divine Comedy, following the Inferno and the Purgatorio. It is an allegory telling of Dante's journey through Heaven, guided by Beatrice, who symbolises theology. In the poem, Paradise is depicted as a series of concentric spheres surrounding the Earth, consisting of the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, the Fixed Stars, the Primum Mobile and finally, the Empyrean. It was written in the early 14th century. Allegorically, the poem represents the soul's ascent to God.

Bondie Dietaiuti was a 13th-century poet from Florence. He was influenced by the Occitan troubadours and known for his animal imagery, including a translation of lines about a lark from the troubadour song Can vei la lauzeta mover. In turn, he has been suggested to be an influence on Dante. Three of his canzoni and four of his sonnets survive. One of his sonnets was included in the Storia della letteratura italiana of Francesco de Sanctis.

References

- ↑ This notation refers to the Bibliographie des Troubadours by Alfred Pillet and Henry Carstens (Halle: Niemeyer, 1933). The 70 refers to Ventadorn, and the 43 is the song number among Ventadorn's works.

- 1 2 Roden, Timothy J.; Wright, Craig; Simms, Bryan R. (2009), "16. Bernart de Ventadorn, Can vei la lauzeta (c.1165)", Anthology for Music in Western Civilization, Volume I, Cengage Learning, p. 29, ISBN 9780495572749 .

- 1 2 Easthope, Antony (1989), "Bernart de Ventadorn: 'Can vei la lauzeta mover' (c. 1170)", Poetry and Phantasy, Cambridge University Press, pp. 75–81, ISBN 9780521355988 .

- ↑ Murray, David (2016), "The clerical reception of Bernart de Ventadorn's 'Can vei la lauzeta mover' (PC 70, 34)", Medium Ævum, 85 (1): 259–267, doi:10.2307/26396373, JSTOR 26396373

- ↑ Paden, William D. (January 1993), "Old Occitan as a lyric language: The insertions from Occitan in three thirteenth-century French romances", Speculum, 68 (1): 36–53, doi:10.2307/2863833

- ↑ Holbrook, Richard Thayer (1902), "Chapter XLI: The Lark", Dante and the Animal Kingdom, Columbia University Press, pp. 266–269

- 1 2 Alighieri, Dante (1984), Musa, Mark (ed.), Dante's Paradise, Indiana University Press, p. 244, ISBN 9780253316196 .

- ↑ Durling, Robert M. (2010), The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri, Volume 3: Paradiso, Oxford University Press, pp. 413–414, ISBN 9780199723355 .

- ↑ Wilhelm, J. J. (2010), Ezra Pound: The Tragic Years, 1925-1972, Penn State Press, p. 50, ISBN 9780271042985 .

- ↑ Bernart de Ventadorn, Quan (Can) vei la lauzeta mover, motet on allmusic.com, 40 versions listed, retrieved 2017-03-22. See also additional variant spellings at allmusic.com.