Reproduction is the biological process by which new individual organisms – "offspring" – are produced from their "parent" or parents. Reproduction is a fundamental feature of all known life; each individual organism exists as the result of reproduction. There are two forms of reproduction: asexual and sexual.

The tree swallow is a migratory bird of the family Hirundinidae. Found in the Americas, the tree swallow was first described in 1807 by French ornithologist Louis Vieillot as Hirundo bicolor. It has since been moved to its current genus, Tachycineta, within which its phylogenetic placement is debated. The tree swallow has glossy blue-green upperparts, with the exception of the blackish wings and tail, and white underparts. The bill is black, the eyes dark brown, and the legs and feet pale brown. The female is generally duller than the male, and the first-year female has mostly brown upperparts, with some blue feathers. Juveniles have brown upperparts, and grey-brown-washed breasts. The tree swallow breeds in the US and Canada. It winters along southern US coasts south, along the Gulf Coast, to Panama and the northwestern coast of South America, and in the West Indies.

Helpers at the nest is a term used in behavioural ecology and evolutionary biology to describe a social structure in which juveniles and sexually mature adolescents of either one or both sexes remain in association with their parents and help them raise subsequent broods or litters, instead of dispersing and beginning to reproduce themselves. This phenomenon was first studied in birds where it occurs most frequently, but it is also known in animals from many different groups including mammals and insects. It is a simple form of co-operative breeding. The effects of helpers usually amount to a net benefit, however, benefits are not uniformly distributed by all helpers nor across all species that exhibit this behaviour. There are multiple proposed explanations for the behaviour, but its variability and broad taxonomic occurrences result in simultaneously plausible theories.

Fecundity is defined in two ways; in human demography, it is the potential for reproduction of a recorded population as opposed to a sole organism, while in population biology, it is considered similar to fertility, the natural capability to produce offspring, measured by the number of gametes (eggs), seed set, or asexual propagules.

Life history theory is an analytical framework designed to study the diversity of life history strategies used by different organisms throughout the world, as well as the causes and results of the variation in their life cycles. It is a theory of biological evolution that seeks to explain aspects of organisms' anatomy and behavior by reference to the way that their life histories—including their reproductive development and behaviors, post-reproductive behaviors, and lifespan —have been shaped by natural selection. A life history strategy is the "age- and stage-specific patterns" and timing of events that make up an organism's life, such as birth, weaning, maturation, death, etc. These events, notably juvenile development, age of sexual maturity, first reproduction, number of offspring and level of parental investment, senescence and death, depend on the physical and ecological environment of the organism.

Cooperative breeding is a social system characterized by alloparental care: offspring receive care not only from their parents, but also from additional group members, often called helpers. Cooperative breeding encompasses a wide variety of group structures, from a breeding pair with helpers that are offspring from a previous season, to groups with multiple breeding males and females (polygynandry) and helpers that are the adult offspring of some but not all of the breeders in the group, to groups in which helpers sometimes achieve co-breeding status by producing their own offspring as part of the group's brood. Cooperative breeding occurs across taxonomic groups including birds, mammals, fish, and insects.

A spongivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating animals of the phylum Porifera, commonly called sea sponges, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their diet, spongivore animals like the hawksbill turtle have developed sharp, narrow bird-like beak that allows them to reach within crevices on the reef to obtain sponges.

Mate desertion occurs when one or both parents abandon their current offspring, and thereby reduce or stop providing parental care. Often, by deserting, a parent attempts to increase breeding opportunities by seeking out another mate. This form of mating strategy behavior is exhibited in insects, birds and mammals. Typically, males are more likely to desert, but both males and females have been observed to practice mate desertion.

Predator satiation is an anti-predator adaptation in which prey briefly occur at high population densities, reducing the probability of an individual organism being eaten. When predators are flooded with potential prey, they can consume only a certain amount, so by occurring at high densities prey benefit from a safety in numbers effect. This strategy has evolved in a diverse range of prey, including notably many species of plants, insects, and fish. Predator satiation can be considered a type of refuge from predators.

The Mojave fringe-toed lizard is a species of medium-sized, white or grayish, black-spotted diurnal lizard in the family Phrynosomatidae. It is adapted to arid climates and is most commonly found in sand dunes within the Mojave Desert. Fringe-toed lizards are characterized by their fringed scales on their hind toes which make locomotion in loose sand possible.

Semelparity and iteroparity are two contrasting reproductive strategies available to living organisms. A species is considered semelparous if it is characterized by a single reproductive episode before death, and iteroparous if it is characterized by multiple reproductive cycles over the course of its lifetime. Iteroparity can be further divided into continuous iteroparity and seasonal iteroparity Some botanists use the parallel terms monocarpy and polycarpy.

Seasonal breeders are animal species that successfully mate only during certain times of the year. These times of year allow for the optimization of survival of young due to factors such as ambient temperature, food and water availability, and changes in the predation behaviors of other species. Related sexual interest and behaviors are expressed and accepted only during this period. Female seasonal breeders will have one or more estrus cycles only when she is "in season" or fertile and receptive to mating. At other times of the year, they will be anestrus, or have a dearth of their sexual cycle. Unlike reproductive cyclicity, seasonality is described in both males and females. Male seasonal breeders may exhibit changes in testosterone levels, testes weight, and fertility depending on the time of year.

Clutch size refers to the number of eggs laid in a single brood by a nesting pair of birds. The numbers laid by a particular species in a given location are usually well defined by evolutionary trade-offs with many factors involved, including resource availability and energetic constraints. Several patterns of variation have been noted and the relationship between latitude and clutch size has been a topic of interest in avian reproduction and evolution. David Lack and R.E. Moreau were among the first to investigate the effect of latitude on the number of eggs per nest. Since Lack's first paper in the mid-1940s there has been extensive research on the pattern of increasing clutch size with increasing latitude. The proximate and ultimate causes for this pattern have been a subject of intense debate involving the development of ideas on group, individual, and gene-centric views of selection.

Fecundity selection, also known as fertility selection, is the fitness advantage resulting from selection on traits that increases the number of offspring. Charles Darwin formulated the theory of fecundity selection between 1871 and 1874 to explain the widespread evolution of female-biased sexual size dimorphism (SSD), where females were larger than males.

Allofeeding is a type of food sharing behaviour observed in cooperatively breeding species of birds. Allofeeding refers to a parent, sibling or unrelated adult bird feeding altricial hatchlings, which are dependent on parental care for their survival. Allofeeding also refers to food sharing between adults of the same species. Allofeeding can occur between mates during mating rituals, courtship, egg laying or incubation, between peers of the same species, or as a form of parental care.

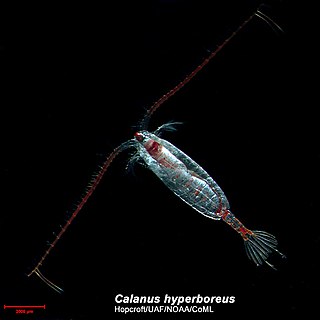

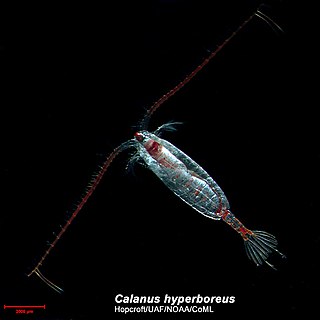

Calanus hyperboreus is a copepod found in the Arctic and northern Atlantic. It occurs from the surface to depths of 5,000 metres (16,000 ft).

Calanus glacialis is an Arctic copepod found in the north-western Atlantic Ocean, adjoining waters, and the northwestern Pacific and its nearby waters. It ranges from sea level to 1,800 metres (5,900 ft) in depth. Females generally range from about 3.6 to 5.5 millimetres in length, and males generally range from about 3.9 to 5.4 millimetres in length.

Calanus helgolandicus is a copepod found in the Atlantic, from the North Sea south to the western coast of Africa. The female has an average size of about 2.9 millimetres (0.11 in) and the male has an average size of about 2.7 millimetres (0.11 in).

Calanus pacificus is a species of copepod found in the Pacific Ocean. The female has an average length of about 3.1 millimetres (0.12 in), and the male has a value of about 2.9 millimetres (0.11 in).

In life history theory, the cost of reproduction hypothesis is the idea that reproduction is costly in terms of future survival and reproduction. This is mediated by various mechanisms, with the two most prominent being hormonal regulation and differential allocation of internal resources.