A crossbow is a ranged weapon using an elastic launching device consisting of a bow-like assembly called a prod, mounted horizontally on a main frame called a tiller, which is hand-held in a similar fashion to the stock of a long gun. Crossbows shoot arrow-like projectiles called bolts or quarrels. A person who shoots crossbow is called a crossbowman or an arbalist.

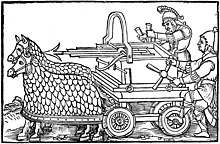

A catapult is a ballistic device used to launch a projectile a great distance without the aid of gunpowder or other propellants – particularly various types of ancient and medieval siege engines. A catapult uses the sudden release of stored potential energy to propel its payload. Most convert tension or torsion energy that was more slowly and manually built up within the device before release, via springs, bows, twisted rope, elastic, or any of numerous other materials and mechanisms.

Medieval warfare is the warfare of the Middle Ages. Technological, cultural, and social advancements had forced a severe transformation in the character of warfare from antiquity, changing military tactics and the role of cavalry and artillery. In terms of fortification, the Middle Ages saw the emergence of the castle in Europe, which then spread to the Holy Land.

The ballista, plural ballistae, sometimes called bolt thrower, was an ancient missile weapon that launched either bolts or stones at a distant target.

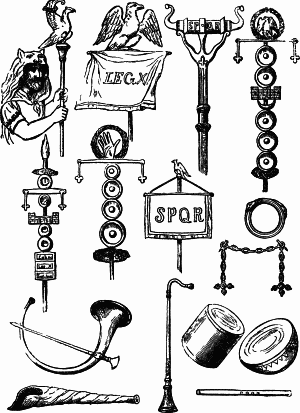

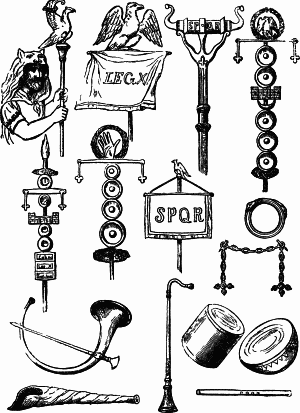

De re militari, also Epitoma rei militaris, is a treatise by the Late Latin writer Publius Flavius Vegetius Renatus about Roman warfare and military principles as a presentation of the methods and practices in use during the height of the Roman Empire and responsible for its power. The extant text dates to the 5th century.

A cohort was a standard tactical military unit of a Roman legion. Although the standard size changed with time and situation, it was generally composed of 480 soldiers. A cohort is considered to be the equivalent of a modern military battalion. The cohort replaced the maniple. From the late second century BC and until the middle of the third century AD, ten cohorts made up a legion. Cohorts were named "first cohort", "second cohort", etc. The first cohort consisted of experienced legionaries, while the legionaries in the tenth cohort were less experienced.

Early thermal weapons, which used heat or burning action to destroy or damage enemy personnel, fortifications or territories, were employed in warfare during the classical and medieval periods.

Roman siege engines were, for the most part, adapted from Hellenistic siege technology. Relatively small efforts were made to develop the technology; however, the Romans brought an unrelentingly aggressive style to siege warfare that brought them repeated success. Up to the first century BC, the Romans utilized siege weapons only as required and relied for the most part on ladders, towers and rams to assault a fortified town. Ballistae were also employed, but held no permanent place within a legion's roster, until later in the republic, and were used sparingly. Julius Caesar took great interest in the integration of advanced siege engines, organizing their use for optimal battlefield efficiency.

The sarcina was the marching pack carried by Roman legionaries, the heavy infantry of the Roman legions.

The gastraphetes, also called belly bow or belly shooter, was a hand-held crossbow used by the Ancient Greeks. It was described in the 1st century AD by the Greek author Heron of Alexandria in his work Belopoeica, which draws on an earlier account of the famous Greek engineer Ctesibius. Heron identifies the gastraphetes as the forerunner of the later catapult, which places its invention some unknown time prior to c. 420 BC.

Roman military personal equipment was produced in large numbers to established patterns, and used in an established manner. These standard patterns and uses were called the res militaris or disciplina. Its regular practice during the Roman Republic and Roman Empire led to military excellence and victory. The equipment gave the Romans a very distinct advantage over their barbarian enemies, especially so in the case of armour. This does not mean that every Roman soldier had better equipment than the richer men among his opponents. Roman equipment was not of a better quality than that used by the majority of Rome's adversaries. Other historians and writers have stated that the Roman army's need for large quantities of "mass produced" equipment after the so-called "Marian Reforms" and subsequent civil wars led to a decline in the quality of Roman equipment compared to the earlier Republican era:

The production of these kinds of helmets of Italic tradition decreased in quality because of the demands of equipping huge armies, especially during civil wars...The bad quality of these helmets is recorded by the sources describing how sometimes they were covered by wicker protections, like those of Pompeius' soldiers during the siege of Dyrrachium in 48 BC, which were seriously damaged by the missiles of Caesar's slingers and archers.

It would appear that armour quality suffered at times when mass production methods were being used to meet the increased demand which was very high the reduced size cuirasses would also have been quicker and cheaper to produce, which may have been a deciding factor at times of financial crisis, or where large bodies of men were required to be mobilized at short notice, possibly reflected in the poor-quality, mass produced iron helmets of Imperial Italic type C, as found, for example, in the River Po at Cremona, associated with the Civil Wars of AD 69 AD; Russell Robinson, 1975, 67

Up until then, the quality of helmets had been fairly consistent and the bowls well decorated and finished. However, after the Marian Reforms, with their resultant influx of the poorest citizens into the army, there must inevitably have been a massive demand for cheaper equipment, a situation which can only have been exacerbated by the Civil Wars...

The strategy of the Roman military contains its grand strategy, operational strategy and, on a small scale, its military tactics. If a fourth rung of "engagement" is added, then the whole can be seen as a ladder, with each level from the foot upwards representing a decreasing concentration on military engagement. Whereas the purest form of tactics or engagement are those free of political imperative, the purest form of political policy does not involve military engagement. Strategy as a whole is the connection between political policy and the use of force to achieve it.

Trajan's First Dacian War took place from 101 to 102.

The scorpio or scorpion was a type of Roman torsion siege engine and field artillery piece. It was described in detail by the early-imperial Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius in the 1st century BC and by the 4th century AD officer and historian Ammianus Marcellinus.

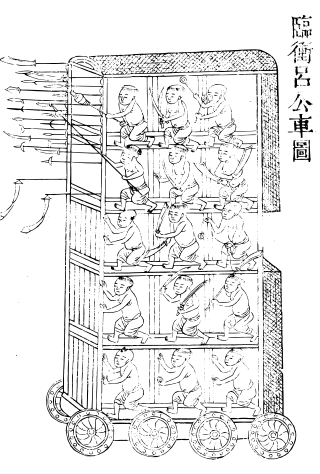

It is not clear where and when the crossbow originated, but it is believed to have appeared in China and Europe around the 7th to 5th centuries BC. In China the crossbow was one of the primary military weapons from the Warring States period until the end of the Han dynasty, when armies were composed of up to 30 to 50 percent crossbowmen. The crossbow lost much of its popularity after the fall of the Han dynasty, likely due to the rise of the more resilient heavy cavalry during the Six Dynasties. One Tang dynasty source recommends a bow to crossbow ratio of five to one as well as the utilization of the countermarch to make up for the crossbow's lack of speed. The crossbow countermarch technique was further refined in the Song dynasty, but crossbow usage in the military continued to decline after the Mongol conquest of China. Although the crossbow never regained the prominence it once had under the Han, it was never completely phased out either. Even as late as the 17th century AD, military theorists were still recommending it for wider military adoption, but production had already shifted in favour of firearms and traditional composite bows.

Ancient Roman technology is the collection of techniques, skills, methods, processes, and engineering practices which supported Roman civilization and made possible the expansion of the economy and military of ancient Rome.

A torsion siege engine is a type of siege engine that utilizes torsion to launch projectiles. They were initially developed by the ancient Macedonians, specifically Philip II of Macedon and Alexander the Great, and used through the Middle Ages until the development of gunpowder artillery in the 14th century rendered them mostly obsolete.

Roman infantry tactics are the theoretical and historical deployment, formation, and manoeuvres of the Roman infantry from the start of the Roman Republic to the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The focus below is primarily on Roman tactics: the "how" of their approach to battle, and how it stacked up against a variety of opponents over time. It does not attempt detailed coverage of things like army structure or equipment. Various battles are summarized to illustrate Roman methods with links to detailed articles on individual encounters.

The Greeks and Romans both made extensive use of artillery for shooting large arrows, bolts or spherical stones or metal balls. Occasionally they also used ranged early thermal weapons. There was heavy siege artillery, but more mobile and lighter field artillery was already known and used in pitched battles, especially in Roman imperial period.

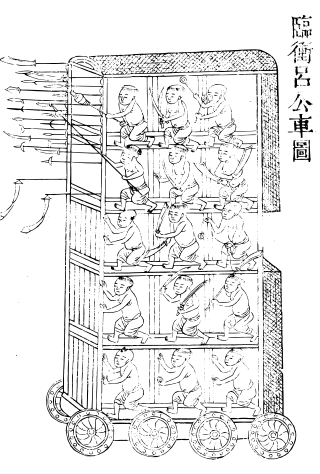

This is an overview of Chinese siege weapons.