Callaway County is a county located in the U.S. state of Missouri. As of the 2020 United States Census, the county's population was 44,283. Its county seat is Fulton. With a border formed by the Missouri River, the county was organized November 25, 1820, and named for Captain James Callaway, grandson of Daniel Boone. The county has been historically referred to as "The Kingdom of Callaway" after an incident in which some residents confronted Union troops during the U.S. Civil War.

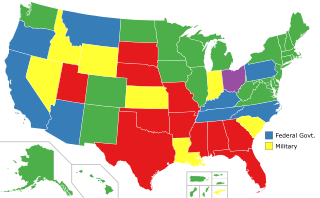

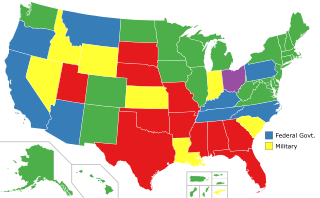

In the United States, capital punishment is a legal penalty in 27 states, throughout the country at the federal level, and in American Samoa. It is also a legal penalty for some military offenses. Capital punishment has been abolished in 23 states and in the federal capital, Washington, D.C. It is usually applied for only the most serious crimes, such as aggravated murder. Although it is a legal penalty in 27 states, 19 of them have authority to execute death sentences, with the other 8, as well as the federal government and military, subject to moratoriums.

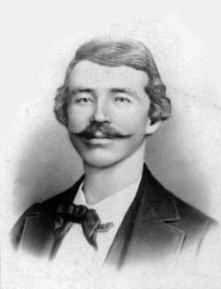

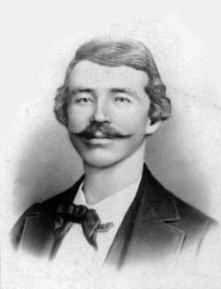

William Clarke Quantrill was a Confederate guerrilla leader during the American Civil War.

John Brown, also known by his slave name, "Fed," was born into slavery on a plantation in Southampton County, Virginia. He is known for his memoir published in London, England in 1855, Slave Life in Georgia: A Narrative of the Life, Sufferings, and Escape of John Brown, a Fugitive Slave, Now in England. This slave narrative, dictated to a helper who wrote it, recounted his life and later escape from slavery in Georgia. He lived in London from 1850 to the end of his life, marrying an English woman.

The New England Emigrant Aid Company was a transportation company founded in Boston, Massachusetts by activist Eli Thayer in the wake of the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which allowed the population of Kansas Territory to choose whether slavery would be legal. The company's ultimate purpose was to transport anti-slavery immigrants into the Kansas Territory. The company believed that if enough anti-slavery immigrants settled en masse in the newly-opened territory, they would be able to shift the balance of political power in the territory, which in turn would lead to Kansas becoming a free state when it eventually joined the United States.

The Textile Workers Union of America (TWUA) was an industrial union of textile workers established through the Congress of Industrial Organizations in 1939 and merged with the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America to become the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union (ACTWU) in 1976. It waged a decades-long campaign to organize J.P. Stevens and other Southern textile manufacturers that achieved some successes.

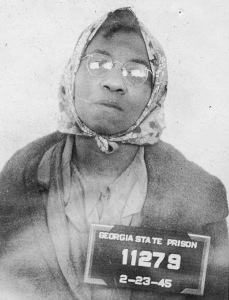

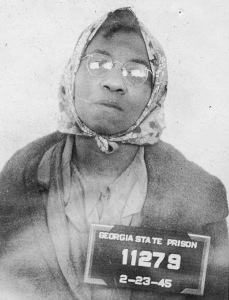

Lena Baker was an African American maid in Cuthbert, Georgia, United States, who was convicted of capital murder of a white man, Ernest Knight. She was executed by the state of Georgia in 1945. Baker was the only woman in Georgia to be executed by electrocution.

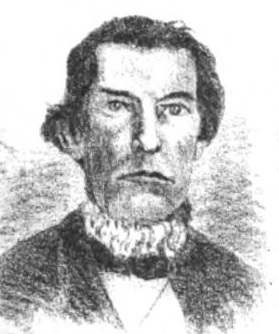

John Jameson was an American farmer, lawyer, and politician from Fulton, Missouri. He represented Missouri in the US House of Representatives.

The North Star was a nineteenth-century anti-slavery newspaper published from the Talman Building in Rochester, New York, by abolitionists Martin Delany and Frederick Douglass. The paper commenced publication on December 3, 1847, and ceased as The North Star in June 1851, when it merged with Gerrit Smith's Liberty Party Paper to form Frederick Douglass' Paper. At the time of the Civil War, it was Douglass' Monthly.

Gerald Thomas Zerkin is an American lawyer. He is a senior assistant federal public defender in Richmond, Virginia.

William Augustus Hall was an American politician who served in the US House of Representatives. He was the son of John H. Hall, industrialist and inventor of the M1819 Hall rifle, the brother of Missouri Governor and Representative Willard Preble Hall and the father of Representative Uriel Sebree Hall and Medal of Honor recipient William Preble Hall.

The history of slavery in Missouri began in 1720, predating statehood, with the large-scale slavery in the region, when French merchant Philippe François Renault brought about 500 slaves of African descent from Saint-Domingue up the Mississippi River to work in lead mines in what is now southeastern Missouri and southern Illinois. These were the first enslaved Africans brought in masses to the middle Mississippi River Valley. Prior to Renault's enterprise, slavery in Missouri under French colonial rule had a much smaller scale compared to elsewhere in the French colonies. Immediately prior to the American Civil War, there were about 100,000 enslaved people in Missouri, about half of whom lived in the 18 western counties near the Kansas border.

The Callaway Plantation, also known as the Arnold-Callaway Plantation, is a set of historical buildings, and an open-air museum located in Washington, Georgia. The site was formerly a working cotton plantation with enslaved African Americans. The site was owned by the Callaway family between 1785 until 1977; however, the family still owns a considerable amount of acreage surrounding the Callaway Plantation. When The plantation was active, it was large in size and owned several hundred slaves.

The treatment of slaves in the United States often included sexual abuse and rape, the denial of education, and punishments like whippings. Families were often split up by the sale of one or more members, usually never to see or hear of each other again.

Rosa Lee Ingram was an African-American sharecropper and widowed mother of 12 children in Georgia, who was at the center of one of the most explosive capital punishment cases in U.S. history. In the 1940s, she became an icon for the civil rights and social justice movement.

State of Missouri v. Celia, a Slave was an 1855 murder trial held in the Circuit Court of Callaway County, Missouri, in which an enslaved woman named Celia was tried for the first-degree murder of her owner, Robert Newsom. Celia was convicted by a jury of twelve white men and sentenced to death. An appeal of the conviction was denied by the Supreme Court of Missouri in December 1855, and Celia was hanged on December 21, 1855.

Annice was the first female slave known to have been executed in Missouri. She was hanged for the murders of five children, two of whom were her own.

Mary was an American enslaved teenager who was hanged for the murder of Vienna Brinker, a two-year-old girl she was babysitting. Her case was notable both for her youth and for the extended legal process that preceded her execution. Although her exact age is unknown, it is generally agreed that she is the youngest person to have been put to death in Missouri.

Rebecca Ann Littleton Hawkins was an American pioneer woman. After enduring twenty years of beatings by her husband, Williamson Hawkins, she hired her neighbor Henry Garster in 1838 to kill him. The murder led to Garster's hanging, the first in Jackson County, Missouri, in 1839. Rebecca had previously attempted and failed to murder Williamson herself with rat poison, for which she was tried and sentenced to five years in the Missouri State Penitentiary. The Jackson County community petitioned the governor for her pardon, which he granted shortly before Rebecca's sentence began. The pardon saved her from the fate of being the first woman to be imprisoned in the Missouri State Penitentiary.

The University of Georgia desegregation riot was an incident of mob violence by proponents of racial segregation on January 11, 1961. The riot was caused by segregationists' protest over the desegregation of the University of Georgia (UGA) in Athens, Georgia following the enrollment of Hamilton E. Holmes and Charlayne Hunter, two African American students. The two had been admitted to the school several days earlier following a lengthy application process that led to a court order mandating that the university accept them. On January 11, several days after the two had registered, a group of approximately 1,000 people conducted a riot outside of Hunter's dormitory. In the aftermath, Holmes and Hunter were suspended by the university's dean, though this suspension was later overturned by a court order. Several rioters were arrested, with several students placed on disciplinary probation, but no one was charged with inciting the riot. In an investigation conducted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, it was revealed that some of the riot organizers were in contact with elected state officials who approved of the riot and assured them of immunity for conducting the riot.