A concerto is, from the late Baroque era, mostly understood as an instrumental composition, written for one or more soloists accompanied by an orchestra or other ensemble. The typical three-movement structure, a slow movement preceded and followed by fast movements, became a standard from the early 18th century.

Robert Wilfred Levick Simpson was an English composer, as well as a long-serving BBC producer and broadcaster.

The Four Seasons is a group of four violin concerti by Italian composer Antonio Vivaldi, each of which gives musical expression to a season of the year. These were composed around 1718−1720, when Vivaldi was the court chapel master in Mantua. They were published in 1725 in Amsterdam, together with eight additional concerti, as Il cimento dell'armonia e dell'inventione.

Dmitri Shostakovich's String Quartet No. 8 in C minor, Op. 110, was written in three days.

Concert champêtre, FP 49, is a harpsichord concerto by Francis Poulenc, which also exists in a version for piano solo with very slight changes in the solo part.

Symphony No. 12 in D minor, Op. 112, subtitled The Year 1917, was composed by Dmitri Shostakovich in 1961. He dedicated it to the memory of Vladimir Lenin. Although the performance on October 1, 1961, by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Yevgeny Mravinsky was billed as the official premiere, the actual first performance took place two hours earlier that same day in Kuybyshev by the Kuybyshev State Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Abram Stasevich.

Nikolai Karlovich Medtner was a Russian composer and virtuoso pianist. After a period of comparative obscurity in the 25 years immediately after his death, he is now becoming recognized as one of the most significant Russian composers for the piano.

Nikolai Yakovlevich Myaskovsky, was a Russian and Soviet composer. He is sometimes referred to as the "Father of the Soviet Symphony". Myaskovsky was awarded the Stalin Prize five times.

Samuel Barber's Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra, Op. 22, completed on 27 November 1945, was the second of his three concertos. Barber was commissioned to write his cello concerto for Raya Garbousova, an expatriate Russian cellist, by Serge Koussevitzky on behalf of Garbusova and the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Funds for the commission were supplied, however, by John Nicholas Brown, an amateur cellist and a trustee of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. The score is dedicated to John and Anne Brown. Barber was still on active duty with the U. S. Army at the time he received the commission, and before beginning work asked Garbousova to play through her repertoire for him so that he could understand her particular performing style and the resources of the instrument. Garbousova premiered it with the Boston Symphony Orchestra in Symphony Hall, Boston, on 5 April 1946, followed by New York performances at the Brooklyn Academy of Music on 12 and 13 April. The concerto won Barber the New York Music Critics' Circle Award in 1947.

Lev Konstantinovich Knipper was a Soviet and Russian composer of partial German descent and an active OGPU/NKVD agent.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart began his series of preserved piano concertos with four that he wrote at the age of 11, in Salzburg: K. 37 and 39–41. The autographs, all held by the Jagiellonian Library, Kraków, are dated by his father as having been completed in April and July of 1767. Although these works were long considered to be original, they are now known to be orchestrations of sonatas by various German virtuosi. The works on which the concertos are based were largely published in Paris, and presumably Mozart and his family became acquainted with them or their composers during their visit to Paris in 1763–64.

The Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor, Op. 23 by Dmitry Kabalevsky was composed in 1935 and then revised in 1973. It is considered in some quarters to be the composer's masterpiece. Its first performance was given in Moscow on May 12, 1936. It consists of three movements:

A solo concerto is a musical form which features a single solo instrument with the melody line, accompanied by an orchestra. Traditionally, there are three movements in a solo concerto, consisting of a fast section, a slow and lyrical section, and then another fast section. However, there are many examples of concertos that do not conform to this plan.

The Piano Concerto No. 3 in D major, Op. 50 by Russian composer Dmitri Kabalevsky is one of three concertos written for and dedicated to young performers within the Soviet Union in 1952, and is sometimes performed as a student's first piano concerto. This sunny and tuneful piece manages to combine effective apparent pianistic pyrotechnics whilst keeping it within the range of ability of a keen student.

The Sonatas for cello and piano No. 4 in C major, Op. 102, No. 1, and No. 5 in D major, Op. 102, No. 2, by Ludwig van Beethoven were composed simultaneously in 1815 and published, by Simrock, in 1817 with a dedication to the Countess Marie von Erdődy, a close friend and confidante of Beethoven.

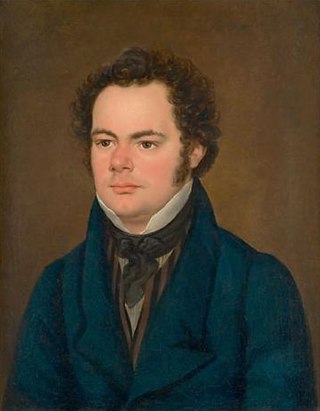

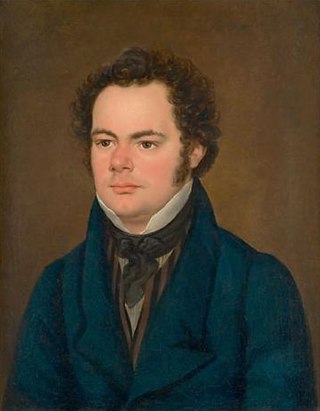

The Fantasia in F minor by Franz Schubert, D.940, for piano four hands, is one of Schubert's most important works for more than one pianist and one of his most important piano works altogether. He composed it in 1828, the last year of his life. A dedication to his former pupil Caroline Esterházy can only be found in the posthumous first edition, not in Schubert's autograph.

The Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 3, by Nikolai Myaskovsky was written in 1908.

Milan Ristić was a Serbian composer, and a member of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts.

Dmitry Borisovich Kabalevsky was a Soviet composer, conductor, pianist and pedagogue of Russian gentry descent.

Symphony No. 0 by Russian composer Alfred Schnittke was composed in 1956–57 whilst Schnittke was a student at the Moscow Conservatory. It was given its first performance in 1957 by the Moscow Conservatory Symphony Orchestra conducted by Algis Zhiuratis. Present at the premiere were Dmitri Shostakovich and Dmitry Kabalevsky.