Related Research Articles

A leap year is a calendar year that contains an additional day compared to a common year. The 366th day is added to keep the calendar year synchronised with the astronomical year or seasonal year. Since astronomical events and seasons do not repeat in a whole number of days, calendars having a constant number of days each year will unavoidably drift over time with respect to the event that the year is supposed to track, such as seasons. By inserting ("intercalating") an additional day—a leap day—or month—a leap month—into some years, the drift between a civilization's dating system and the physical properties of the Solar System can be corrected.

The Roman calendar was the calendar used by the Roman Kingdom and Roman Republic. Although the term is primarily used for Rome's pre-Julian calendars, it is often used inclusively of the Julian calendar established by Julius Caesar in 46 BC.

The Ides of March is the day on the Roman calendar marked as the Idus, roughly the midpoint of a month, of Martius, corresponding to 15 March on the Gregorian calendar. It was marked by several major religious observances. In 44 BC, it became notorious as the date of the assassination of Julius Caesar, which made the Ides of March a turning point in Roman history.

Saturnalia is an ancient Roman festival and holiday in honour of the god Saturn, held on 17 December in the Julian calendar and later expanded with festivities until 19 December. By the 1st century BC, the celebration had been extended until 23 December, for a total of seven days of festivities. The holiday was celebrated with a sacrifice at the Temple of Saturn, in the Roman Forum, and a public banquet, followed by private gift-giving, continual partying, and a carnival atmosphere that overturned Roman social norms: gambling was permitted, and masters provided table service for their slaves as it was seen as a time of liberty for both slaves and freedmen alike. A common custom was the election of a "King of the Saturnalia", who gave orders to people, which were followed and presided over the merrymaking. The gifts exchanged were usually gag gifts or small figurines made of wax or pottery known as sigillaria. The poet Catullus called it "the best of days".

In the Gregorian calendar, New Year's Day is the first day of the calendar year, 1 January. Most solar calendars, such as the Gregorian and Julian calendars, begin the year regularly at or near the northern winter solstice. In contrast, cultures and religions that observe a lunisolar or lunar calendar celebrate their Lunar New Year at varying points relative to the solar year.

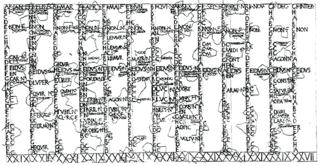

Festivals in ancient Rome were a very important part in Roman religious life during both the Republican and Imperial eras, and one of the primary feat of "holy days"; singular also feriae or dies ferialis) were either public (publicae) or private (privatae). State holidays were celebrated by the Roman people and received public funding. Games (ludi), such as the Ludi Apollinares, were not technically feriae, but the days on which they were celebrated were dies festi, holidays in the modern sense of days off work. Although feriae were paid for by the state, ludi were often funded by wealthy individuals. Feriae privatae were holidays celebrated in honor of private individuals or by families. This article deals only with public holidays, including rites celebrated by the state priests of Rome at temples, as well as celebrations by neighborhoods, families, and friends held simultaneously throughout Rome.

The calends or kalends is the first day of every month in the Roman calendar. The English word "calendar" is derived from this word.

The Consualia or Consuales Ludi was the name of two ancient Roman festivals in honor of Consus, a tutelary deity of the harvest and stored grain. Consuales Ludi harvest festivals were held on August 21, and again on December 15, in connection with grain storage. The shrine of Consus was underground, it was covered with earth all year and was only uncovered for this one day. Mars, the god of war, as a protector of the harvest, was also honored on this day, as were the Lares, the household gods that individual families held sacred.

The Feast of San Gennaro, also known as San Gennaro Festival, is a Neapolitan and Italian-American patronal festival dedicated to Saint Januarius, patron saint of Naples and Little Italy, New York.

Februarius, fully Mensis Februarius, was the shortest month of the Roman calendar from which the Julian and Gregorian month of February derived. It was eventually placed second in order, preceded by Ianuarius and followed by Martius. In the oldest Roman calendar, which the Romans believed to have been instituted by their legendary founder Romulus, March was the first month, and the calendar year had only ten months in all. Ianuarius and Februarius were supposed to have been added by Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome, originally at the end of the year. It is unclear when the Romans reset the course of the year so that January and February came first.

The Feast of Fools or Festival of Fools was a feast day on January 1 celebrated by the clergy in Europe during the Middle Ages, initially in Southern France, but later more widely. During the Feast, participants would elect either a false Bishop, false Archbishop, or false Pope. Ecclesiastical ritual would also be parodied, and higher and lower-level clergy would change places. The lack of surviving documents or accounts, as well as changing cultural and religious norms, has considerably obscured the modern understanding of the Feast, which originated in proper liturgical observance, and has more to do with other examples of medieval liturgical drama, though there is some connection with the earlier pagan (Roman) feasts of Saturnalia and Kalends or the later bourgeois in Sotie. Over the course of a week, the ceremonies would be led by different people in positions of power within the church. On December 26, St. Stephen's Day, the deacons led the ceremonies. The sub-priests were in charge on December 27, St. John's Day, the choirboys on December 28, Holy Innocents’ Day, and the sub-deacons on the first of January, the Feast of the Circumcision. There is some disagreement on whether the term Feast of Fools was originally used to refer to the collection of days or specifically the celebrations taking place on the first of January. The word "fool" is used as a synonym for humble, as was common in the 11th century, rather than the modern use that treats it as another term for clown or jester.

The Three Pilgrimage Festivals or Three Pilgrim Festivals, sometimes known in English by their Hebrew name Shalosh Regalim, are three major festivals in Judaism—two in spring; Passover, 49 days later Shavuot ; and in autumn Sukkot —when all Israelites who were able were expected to make a pilgrimage to the Temple in Jerusalem as commanded by the Torah. In Jerusalem, they would participate in festivities and ritual worship in conjunction with the services of the kohanim (priests) at the Temple.

The Feast of the Ass is a medieval Christian feast observed on 14 January, celebrating the flight into Egypt. It was originally celebrated primarily in France, as a by-product of the Feast of Fools celebrating the donkey-related stories in the Bible, in particular the donkey bearing the Holy Family into Egypt after Jesus' birth.

An Agonalia or Agonia was an obscure archaic religious observance celebrated in ancient Rome several times a year, in honor of various divinities. Its institution, like that of other religious rites and ceremonies, was attributed to Numa Pompilius, the semi-legendary second king of Rome. Ancient calendars indicate that it was celebrated regularly on January 9, May 21, and December 11.

Ianuarius, Januarius, or January, fully Mensis Ianuarius and abbreviated Ian., was the first month of the ancient Roman calendar, from which the Julian and Gregorian month of January derived. It was followed by Februarius ("February"). In the calendars of the Roman Republic, Ianuarius had 29 days. Two days were added when the calendar was reformed under Julius Caesar in 45 BCE.

The Compitalia was an annual festival in ancient Roman religion held in honor of the Lares Compitales, household deities of the crossroads, to whom sacrifices were offered at the places where two or more ways met.

The Nativity of John the Baptist is a Christian feast day. It is observed annually on 24 June. The Nativity of John the Baptist is a high-ranking liturgical feast, kept in the Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church, Anglicanism, and Lutheranism. The sole biblical account of the birth of John the Baptist comes from the Gospel of Luke.

The Feast of the Annunciation commemorates the visit of the archangel Gabriel to the Virgin Mary, during which he informed her that she would be the mother of Jesus Christ, the Son of God. It is celebrated on 25 March; however, if 25 March falls either in Holy Week or in Easter Week, the feast is postponed to the Monday after the Second Sunday of Easter.

Haloa or Alo (Ἁλῶα) was an Attic festival, celebrated principally at Eleusis, in honour of Demeter, protector of the fruits of the earth, of Dionysus, god of the grape and of wine, and Poseidon, god of the seashore vegetation. In Greek, the word hálōs (ἅλως) from which Haloa derives means “threshing-floor” or “garden.” While the general consensus is that it was a festival related to threshing—the process of loosening the edible part of cereal grain after harvest—some scholars disagree and argue that it was instead a gardening festival. Haloa focuses mainly on the “first fruits” of the harvest, partly as a grateful acknowledgement for the benefits the husbandmen received, partly as prayer that the next harvest would be plentiful. The festival was also called Thalysia or Syncomesteria.

Aprilis or mensis Aprilis (April) was the fourth month of the ancient Roman calendar in the classical period, following Martius (March) and preceding Maius (May). On the oldest Roman calendar that had begun with March, Aprilis had been the second of ten months in the year. April had 29 days on calendars of the Roman Republic, with a day added to the month during the reform in the mid-40s BC that produced the Julian calendar.

References

- ↑ Miles, Clement A. (1912). Christmas in Ritual and Tradition. from Chapter XIII: Masking, the Mummers’ Play, the Feast of Fools, and the Boy Bishop, "Mr. Chambers's theory is that the ass was a descendant of the cervulus or hobby-buck who figures so largely in ecclesiastical condemnations of Kalends customs."

- ↑ "It took place on the kalends of January and was a kind of New Year's festival, at which people exchange strenae (étrennes, 'gifts') dressed up as animals or old women, and danced through the streets singing, the applause of the populace. According to DuCange (s.v. cervulus), sacrilegious songs were sung. This happened even in the vicinity of St. Peter's in Rome".Jung, C. G. (1968). The archetypes and the collective unconscious. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. pp. 257 fn. 3. ISBN 0-691-01833-2.