String instruments, stringed instruments, or chordophones are musical instruments that produce sound from vibrating strings when a performer plays or sounds the strings in some manner.

Zithers are a class of stringed instruments. Historically, the name has been applied to any instrument of the psaltery family, or to an instrument consisting of many strings stretched across a thin, flat body. This article describes the latter variety.

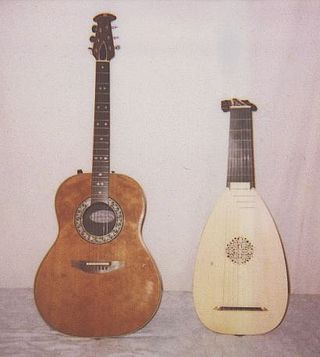

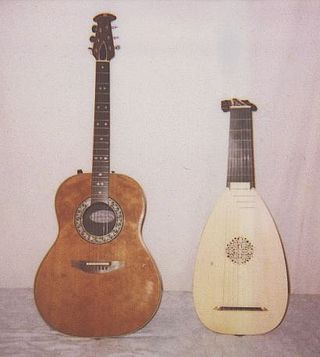

The cittern or cithren is a stringed instrument dating from the Renaissance. Modern scholars debate its exact history, but it is generally accepted that it is descended from the Medieval citole. Its flat-back design was simpler and cheaper to construct than the lute. It was also easier to play, smaller, less delicate and more portable. Played by people of all social classes, the cittern was a premier instrument of casual music-making much as is the guitar today.

The bandora or bandore is a large long-necked plucked string-instrument that can be regarded as a bass cittern though it does not have the re-entrant tuning typical of the cittern. Probably first built by John Rose in England around 1560, it remained popular for over a century. A somewhat smaller version was the orpharion.

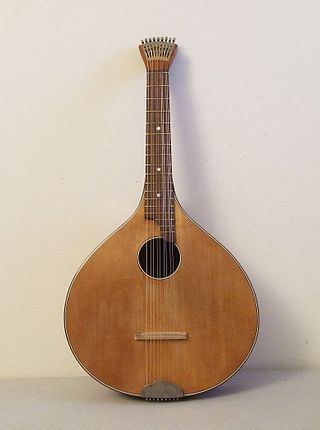

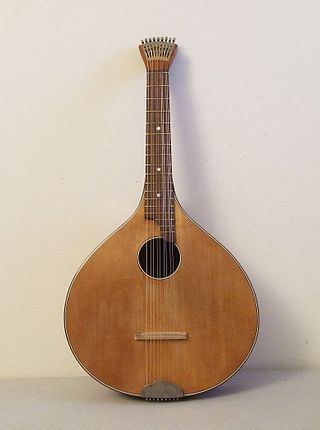

The Portuguese guitar or Portuguese guitarra is a plucked string instrument with twelve steel strings, strung in six courses of two strings. It is one of the few musical instruments that still uses watch-key or Preston tuners. It is iconically associated with the musical genre known as Fado, and is now an icon for anything Portuguese.

The Irish bouzouki is an adaptation of the Greek bouzouki. The newer Greek tetrachordo bouzouki was introduced into Irish traditional music in the mid-1960s by Johnny Moynihan of the folk group Sweeney's Men. Alec Finn, first in the Cana Band and subsequently in De Dannan, introduced the first Greek trichordo (3 course) bouzouki into Irish music.

The waldzither is a plucked string instrument from Germany that came up around 1900 in Thuringia. It is a type of cittern that has nine steel strings in five courses. Different types of waldzither come in different tunings, which are generally open tunings as usual in citterns. The most common type has the tuning C3*G3 G3*C4 C4*E4 E4*G4 G4.

The citole was a string musical instrument, closely associated with the medieval fiddles and commonly used from 1200–1350. It was known by other names in various languages: cedra, cetera, cetola, cetula, cistola, citola, citula, citera, chytara, cistole, cithar, cuitole, cythera, cythol, cytiole, cytolys, gytolle, sitole, sytholle, sytole, and zitol. Like the modern guitar, it was manipulated at the neck to get different notes, and picked or strummed with a plectrum. Although it was largely out of use by the late 14th century, the Italians "re-introduced it in modified form" in the 16th century as the cetra, and it may have influenced the development of the guitar as well. It was also a pioneering instrument in England, introducing the populace to necked, plucked instruments, giving people the concepts needed to quickly switch to the newly arriving lutes and gitterns. Two possible descendant instrument are the Portuguese guitar and the Corsican Cetera, both types of cittern.

The orpharion or opherion is a plucked stringed instrument from the Renaissance, a member of the cittern family. Its construction is similar to the larger bandora and an ancestor of the guitar. The metal strings are tuned like a lute and are plucked with the fingers. The nut and bridge of an orpharion are typically sloped, so that the string length increases from treble to bass. Due to the extremely low-tension metal strings, which would easily distort the notes when pushed down, the frets were almost flush with the fingerboard, which was gently scalloped. As with all metal-strung instruments of the era, a very light touch with the plucking hand was required, quite different from the sharper attack used on the lute.

Cetra, a Latin word borrowed from Greek, is an Italian descendant of κιθάρα (cithara). It is a synonym for the cittern but has been used for the citole and cithara and cythara.

Plucked string instruments are a subcategory of string instruments that are played by plucking the strings. Plucking is a way of pulling and releasing the string in such a way as to give it an impulse that causes the string to vibrate. Plucking can be done with either a finger or a plectrum.

There are many varieties of ten-string guitar, including:

This is a chart of stringed instrument tunings. Instruments are listed alphabetically by their most commonly known name.

The cythara is a wide group of stringed instruments of medieval and Renaissance Europe, including not only the lyre and harp but also necked, string instruments. In fact, unless a medieval document gives an indication that it meant a necked instrument, then it likely was referring to a lyre. It was also spelled cithara or kithara and was Latin for the Greek lyre. However, lacking names for some stringed instruments from the medieval period, these have been referred to as fiddles and citharas/cytharas, both by medieval people and by modern researchers. The instruments are important as being ancestors to or influential in the development of a wide variety of European instruments, including fiddles, vielles, violas, citoles and guitars. Although not proven to be completely separate from the line of lute-family instruments that dominated Europe, arguments have been made that they represent a European-based tradition of instrument building, which was for a time separate from the lute-family instruments.

Gregory Doc Rossi known professionally as Doc Rossi, is a citternist, composer and scholar born in Dayton, Ohio in 1955, emigrating to Europe in 1984. Today, he lives in Portugal after spending some years in Italy and Corsica. He studied music from an early age and began performing at 14. He has B.A.s in Music and English Literature, and was awarded the Ph.D. in 1991 from the University of London, where he wrote on Shakespeare and Brecht under the supervision of René Weis and Keith Walker. He studied historical technique with Andrea Damiani and has had tuition from John Renbourn, Ugo Orlandi, Richard Strasser, Christopher Morrongiello, Ljubo Majstorovic and John Anthony Lennon. Rossi has had a lifelong interest in the cittern, having built one at the age of 13. He now performs on a variety of instruments, including the diatonic Renaissance cittern, the modern Celtic cittern, the Corsican cetera, and especially the so-called English guittar (sic) or cetra, an 18th-century instrument. He also plays fingerstyle guitar, bass guitar, tenor banjo, and mandolin family instruments.

Laúd is a plectrum-plucked chordophone from Spain, played also in diaspora countries such as Cuba and the Philippines.

The English guitar or guittar is a stringed instrument – a type of cittern – popular in many places in Europe from around 1750–1850. It is unknown when the identifier "English" became connected to the instrument: at the time of its introduction to Great Britain, and during its period of popularity, it was apparently simply known as guitar or guittar. The instrument was also known in Norway as a guitarre and France as cistre or guitarre allemande. There are many examples in Norwegian museums, like the Norsk Folkemuseum and in British ones, including the Victoria and Albert Museum. The English guitar has a pear-shaped body, a flat base, and a short neck. The instrument is also related to the Portuguese guitar and the German waldzither.

The halszither is a stringed instrument from Switzerland. It has nine steel strings in five courses and is tuned: G2, D3 D3, G3 G3, B3 B3, D4 D4.

Repetitive tunings are alternative tunings for the guitar. A repetitive tuning begins with a list of notes that is duplicated, either at unison or at higher octaves.

The Cithrinchen or Bell cittern was a distinctively shaped instrument of the renaissance and baroque periods. It was usually strung with doubled courses of thin, light tension brass or steel strings. It usually had 3 soundholes and 5 courses (pairs) of strings. It was popular in Germany, England and Sweden.