This article relies largely or entirely on a single source .(June 2019) |

Chaim HaKohen of Aram Zobah (Aleppo) (Egypt 1585- Italy 1655) was an Egyptian Rabbi.

This article relies largely or entirely on a single source .(June 2019) |

Chaim HaKohen of Aram Zobah (Aleppo) (Egypt 1585- Italy 1655) was an Egyptian Rabbi.

His father was Rabbi Abraham HaKohen, who belonged to a famous family of Kohanim, descendants of Yosef HaCohen from Spain.[ citation needed ]

As a child, while his classmates spent their free time playing, Chaim went to the synagogue to study Torah, and to learn how to serve God. As a teenager, on Shabbat, he would climb into the pulpit and give sermons on the Torah portion (the parashah), on the laws related to Jewish festivities, and give on Musar (Jewish ethics).[ citation needed ]

After becoming a Rabbi, HaKohen moved to the city of Safed. There he studied with the rabbi and kabbalist Chaim Vital for three years. From Safed, HaKohen moved to Aram Tsoba, located near Aleppo, Syria, where he settled permanently. He was elected rabbi, replacing Mordechai HaKohen, son-in-law of Shmuel Laniado (Baal HaKelim).[ citation needed ]

Under Rabbi HaKohen Torah study flourished, even more than in Aleppo. New Talmudic schools and academies were established, and more benches were added to the synagogue. [ citation needed ]

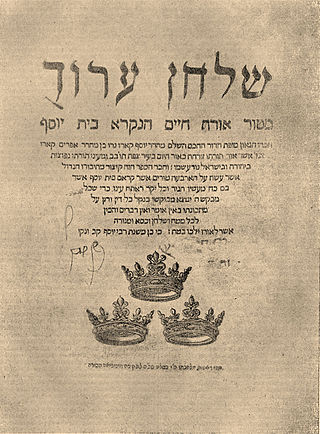

HaKohen served the Aleppo community as rabbi and head of the rabbinical court for decades. With exhaustive knowledge, he answered complex rabbinical questions, sometimes sent by members of distant Jewish communities. Eventually, he decided to organize his writings and publish books, especially his commentaries on Shulchan Aruch, the legal code that was written by his teacher's teacher, rabbi and kabbalist Joseph Karo.[ citation needed ]

Rabbi HaKohen wrote many other works. These include his commentaries on the Song of Songs (Shir HaShirim), the Book of Lamentations, the Book of Ruth, the Book of Daniel, and many other manuscripts. The printing press had not yet arrived in Aleppo and books were reproduced by hand. The best printers of the time were in Venice, Italy, where half of European books were published during most of the 16th century. The first edition of the Babylonian Talmud was printed there, along with the first edition of Shulchan Aruch, by the rabbi and kabbalist Joseph Karo.[ citation needed ]

Rabbi HaKohen sent his commentary on the Book of Esther to Venice. As time passed and the book did not appear, Rabbi HaKohen decided to travel to Venice, and personally oversee its printing. Together with his son they traveled by sea carrying all the Rabbi's manuscripts. His ship was attacked by Maltese pirates. As the pirates boarded the ship, HaKohen and his son jumped into the sea, but their books remained on the ship.[ citation needed ]

Rabbi HaKohen spent several years in Italy, rewriting his lost books.[ citation needed ] The first book that he was able to print, with the help of Moses Zacuto, was entitled Torat Chacham (The Teaching of the Wise). This book was a collection of the rabbi's sermons on the weekly sections of the Torah. The book was published in Venice in 1654.

His next book was Mekor Chaim (The Source of Life). This book is a commentary of Shulchan Aruch, consisting of several volumes. The first volumes were published in Venice, also in 1654. To print the second volume of his book Pitda, the rabbi travelled to Livorno, Italy, where he died in 1655. After his death, some of his pirated books were recovered.[ citation needed ]

Rabbi Yosef Jaim David Azulai (Hida), in his chronicle book Shem HaGuedolim, states that he had in his hands HaKohen's manuscript Ateret Zahab, a commentary on the Book of Esther. Migdal David, a commentary on the Book of Ruth, was also found. The book was printed in Amsterdam in 1680 by an impostor who falsely claimed authorship. The Talmudic commentaries on the Berachot treatise were published in the Israeli monthly publication Qobets Bet Aharon ve Israel, in 1983. Some of HaKohen's books and commentaries exist as manuscripts and remain unpublished. [1]

Halakha, also transliterated as halacha, halakhah, and halocho, is the collective body of Jewish religious laws that are derived from the Written and Oral Torah. Halakha is based on biblical commandments (mitzvot), subsequent Talmudic and rabbinic laws, and the customs and traditions which were compiled in the many books such as the Shulchan Aruch. Halakha is often translated as "Jewish law", although a more literal translation of it might be "the way to behave" or "the way of walking". The word is derived from the root which means "to behave". Halakha not only guides religious practices and beliefs, it also guides numerous aspects of day-to-day life.

Rabbinic literature, in its broadest sense, is the entire spectrum of rabbinic writings throughout Jewish history. However, the term often refers specifically to literature from the Talmudic era, as opposed to medieval and modern rabbinic writing, and thus corresponds with the Hebrew term Sifrut Chazal. This more specific sense of "Rabbinic literature"—referring to the Talmudim, Midrash, and related writings, but hardly ever to later texts—is how the term is generally intended when used in contemporary academic writing. The terms mefareshim and parshanim (commentaries/commentators) almost always refer to later, post-Talmudic writers of rabbinic glosses on Biblical and Talmudic texts.

The Shulchan Aruch, sometimes dubbed in English as the Code of Jewish Law, is the most widely consulted of the various legal codes in Judaism. It was authored in Safed, Ottoman Syria by Joseph Karo in 1563 and published in Venice two years later. Together with its commentaries, it is the most widely accepted compilation of halakha or Jewish law ever written.

The Mishnah Berurah is a work of halakha by Rabbi Yisrael Meir Kagan. It is a commentary on Orach Chayim, the first section of the Shulchan Aruch which deals with laws of prayer, synagogue, Shabbat and holidays, summarizing the opinions of the Acharonim on that work.

The Mishneh Torah, also known as Sefer Yad ha-Hazaka, is a code of Rabbinic Jewish religious law (halakha) authored by Maimonides. The Mishneh Torah was compiled between 1170 and 1180 CE, while Maimonides was living in Egypt, and is regarded as Maimonides' magnum opus. Accordingly, later sources simply refer to the work as "Maimon", "Maimonides", or "RaMBaM", although Maimonides composed other works.

Arba'ah Turim, often called simply the Tur, is an important Halakhic code composed by Yaakov ben Asher. The four-part structure of the Tur and its division into chapters (simanim) were adopted by the later code Shulchan Aruch. This was the first book to be printed in Southeast Europe and the Near East.

Yechiel Michel ha-Levi Epstein (24 January 1829 – 25 March 1908), often called "the Aruch haShulchan" after his magnum opus, Aruch HaShulchan, was a Rabbi and posek in Lithuania.

A Torah database is a collection of classic Jewish texts in electronic form, the kinds of texts which, especially in Israel, are often called "The Traditional Jewish Bookshelf" ; the texts are in their original languages. These databases contain either keyed-in digital texts or a collection of page-images from printed editions. Given the nature of traditional Jewish Torah study, which involves extensive citation and cross-referencing among hundreds of texts written over the course of thousands of years, many Torah databases also make extensive use of hypertext links.

In Jewish law and history, Acharonim are the leading rabbis and poskim living from roughly the 16th century to the present, and more specifically since the writing of the Shulchan Aruch in 1563 CE.

Rabbi Moses Isserles, also known by the acronym Rema, was an eminent Polish Ashkenazi rabbi, talmudist, and posek.

David ha-Levi Segal, also known as the Turei Zahav after the title of his significant halakhic commentary on the Shulchan Aruch, was one of the greatest Polish rabbinical authorities.

Orach Chayim, is a section of Rabbi Jacob ben Asher's compilation of Halakha, Arba'ah Turim. This section addresses aspects of Jewish law pertinent to the Hebrew calendar. Rabbi Yosef Karo modeled the framework of the Shulkhan Arukh, his own compilation of practical Jewish law, after the Arba'ah Turim. Many later commentators used this framework, as well. Thus, Orach Chayim in common usage may refer to another area of halakha, separate from Rabbi Jacob ben Asher's compilation.

Abraham Abele Gombiner, known as the Magen Avraham, born in Gąbin (Gombin), Poland, was a rabbi, Talmudist and a leading religious authority in the Jewish community of Kalisz, Poland during the seventeenth century. His full name is Avraham Abele ben Chaim HaLevi from the town of Gombin. There are texts that list his family name as Kalisz after the city of his residence. After his parents were killed in 1655 during the aftermath of the Chmielnicki massacres of 1648, he moved to live and study with his relative in Leszno, Jacob Isaac Gombiner. From there he moved to Kalisz where he was appointed as Rosh Yeshiva and judge in the tribunal of Rabbi Israel Spira.

Chaim ibn Attar or Ḥayyim ben Moshe ibn Attar also known as the Or ha-Ḥayyim after his popular commentary on the Torah, was a Talmudist and Kabbalist. He is arguably considered to be one of the most prominent Rabbis of Morocco, and is highly regarded in Hassidic Judaism.

Yaakov ben Yaakov Moshe Lorberbaum of Lissa (1760-1832) was a rabbi and posek. He is most commonly known as the "Ba'al HaChavas Da'as" or "Ba'al HaNesivos" for his most well-known works, or as the "Lissa Rav" for the city in which he was Chief Rabbi.

Shnayim mikra ve-echad targum, is the Jewish practice of reading the weekly Torah portion in a prescribed manner. In addition to hearing the Torah portion read in the synagogue, a person should read it himself twice during that week, together with a translation usually by Targum Onkelos and/or Rashi's commentary. In addition, while not required by law, there exists an Ashkenazi custom to also read the portion from the Prophets with its targum.

Sifrei Kodesh, commonly referred to as sefarim, or in its singular form, sefer, are books of Jewish religious literature and are viewed by religious Jews as sacred. These are generally works of Torah literature, i.e. Tanakh and all works that expound on it, including the Mishnah, Midrash, Talmud, and all works of halakha, Musar, Hasidism, Kabbalah, or machshavah. Historically, sifrei kodesh were generally written in Hebrew with some in Judeo-Aramaic or Arabic, although in recent years, thousands of titles in other languages, most notably English, were published. An alternative spelling for 'sefarim' is seforim.

The gift of the foreleg, cheeks and maw of a kosher-slaughtered animal to a kohen is a positive commandment in the Hebrew Bible. The Shulchan Aruch rules that after the slaughter of animal by a shochet, the shochet is required to separate the cuts of the foreleg, cheek and maw and give them to a kohen freely, without the kohen paying or performing any service.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Judaism:

The prohibition of Kohen defilement to the dead is the commandment to a Jewish priest (kohen) not to come in direct contact with, or be in the same enclosed roofed space as a dead human body.