Hoplites were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greek city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with fewer soldiers. The formation discouraged the soldiers from acting alone, for this would compromise the formation and minimize its strengths. The hoplites were primarily represented by free citizens – propertied farmers and artisans – who were able to afford a linen or bronze armour suit and weapons. They also appear in the stories of Homer, but it is thought that their use began in earnest around the 7th century BC, when weapons became cheap during the Iron Age and ordinary citizens were able to provide their own weapons. Most hoplites were not professional soldiers and often lacked sufficient military training. Some states maintained a small elite professional unit, known as the epilektoi or logades because they were picked from the regular citizen infantry. These existed at times in Athens, Sparta, Argos, Thebes, and Syracuse, among other places. Hoplite soldiers made up the bulk of ancient Greek armies.

Infantry is a specialization of military personnel who engage in warfare combat. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, irregular infantry, heavy infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry, mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and naval infantry. Other types of infantry, such as line infantry and mounted infantry, were once commonplace but fell out of favor in the 1800s with the invention of more accurate and powerful weapons.

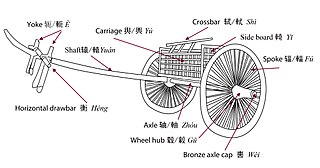

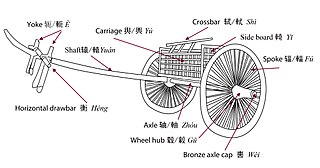

A chariot is a type of vehicle similar to a cart, driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, dated to c. 1950–1880 BC and are depicted on cylinder seals from Central Anatolia in Kültepe dated to c. 1900 BC. The critical invention that allowed the construction of light, horse-drawn chariots was the spoked wheel.

The Battle of the Sabis also known as the Battle of the Sambre or the Battle against the Nervians was fought in 57 BC near modern Saulzoir in Northern France, between Caesar's legions and an association of Belgae tribes, principally the Nervii. Julius Caesar, commanding the Roman forces, was surprised and nearly defeated. According to Caesar's report, a combination of determined defence, skilled generalship, and the timely arrival of reinforcements allowed the Romans to turn a strategic defeat into a tactical victory. Few primary sources describe the battle in detail, with most information coming from Caesar's own report on the battle from his book, Commentarii de Bello Gallico. Little is therefore known about the Nervii perspective on the battle.

The scythed chariot was a war chariot with scythe blades mounted on each side. It was employed in ancient times.

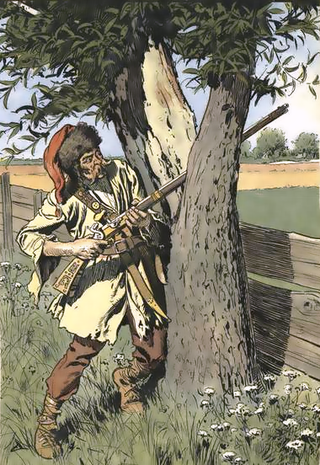

Skirmishers are light infantry or light cavalry soldiers deployed as a vanguard, flank guard or rearguard to screen a tactical position or a larger body of friendly troops from enemy advances. They are usually deployed in a skirmish line, an irregular open formation that is much more spread out in depth and in breadth than a traditional line formation. Their purpose is to harass the enemy by engaging them in only light or sporadic combat to delay their movement, disrupt their attack, or weaken their morale. Such tactics are collectively called skirmishing. A combat with only light, relatively indecisive combat is often called a skirmish even if heavier troops are sometimes involved.

Ancient warfare is war that was conducted from the beginning of recorded history to the end of the ancient period. The difference between prehistoric and ancient warfare is more organization oriented than technology oriented. The development of first city-states, and then empires, allowed warfare to change dramatically. Beginning in Mesopotamia, states produced sufficient agricultural surplus. This allowed full-time ruling elites and military commanders to emerge. While the bulk of military forces were still farmers, the society could portion off each year. Thus, organized armies developed for the first time. These new armies were able to help states grow in size and become increasingly centralized.

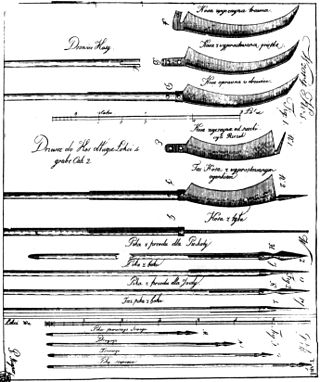

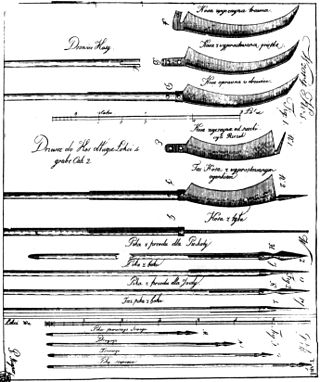

A war scythe or military scythe is a form of polearm with a curving single-edged blade with the cutting edge on the concave side of the blade. Its blade bears a superficial resemblance to that of an agricultural scythe from which it is likely to have evolved, but the war scythe is otherwise unrelated to agricultural tools and is a purpose-built infantry melee weapon. The blade of a war scythe has regularly proportioned flats, a thickness comparable to that of a spear or sword blade, and slightly curves along its edge as it tapers to its point. This is different from farming scythes, which have very thin and irregularly curved blades, specialised for mowing grass and wheat only, unsuitable as blades for improvised spears or polearms.

In the course of his Gallic Wars, Julius Caesar invaded Britain twice: in 55 and 54 BC. On the first occasion, Caesar took with him only two legions, and achieved little beyond a landing on the coast of Kent. The second invasion consisted of 800 ships, five legions and 2,000 cavalry. The force was so imposing that the Celtic Britons did not contest Caesar's landing, waiting instead until he began to move inland. Caesar eventually penetrated into Middlesex and crossed the Thames, forcing the British warlord Cassivellaunus to pay tribute to Rome and setting up Mandubracius of the Trinovantes as a client king. The Romans then returned to Gaul without conquering any territory.

For much of history, humans have used some form of cavalry for war and, as a result, cavalry tactics have evolved over time. Tactically, the main advantages of cavalry over infantry were greater mobility, a larger impact, and a higher riding position.

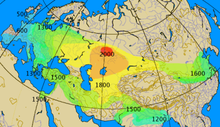

The first evidence of horses in warfare dates from Eurasia between 4000 and 3000 BC. A Sumerian illustration of warfare from 2500 BC depicts some type of equine pulling wagons. By 1600 BC, improved harness and chariot designs made chariot warfare common throughout the Ancient Near East, and the earliest written training manual for war horses was a guide for training chariot horses written about 1350 BC. As formal cavalry tactics replaced the chariot, so did new training methods, and by 360 BC, the Greek cavalry officer Xenophon had written an extensive treatise on horsemanship. The effectiveness of horses in battle was also revolutionized by improvements in technology, such as the invention of the saddle, the stirrup, and the horse collar.

Ancient Egypt was an ancient civilization of eastern North Africa, concentrated along the northern reaches of the Nile River in Egypt. The civilization coalesced around 3150 BC with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh, and it developed over the next three millennia. Its history occurred in a series of stable kingdoms, separated by periods of relative instability known as intermediate periods. Ancient Egypt reached its pinnacle during the New Kingdom, after which it entered a period of slow decline. Egypt was conquered by a succession of foreign powers in the late period, and the rule of the pharaohs officially ended in 31 BC, when the early Roman Empire conquered Egypt and made it a province. Although the Egyptian military forces in the Old and Middle kingdoms were well maintained, the new form that emerged in the New Kingdom showed the state becoming more organized to serve its needs.

A javelin is a light spear designed primarily to be thrown, historically as a ranged weapon. Today, the javelin is predominantly used for sporting purposes such as the javelin throw. The javelin is nearly always thrown by hand, unlike the sling, bow, and crossbow, which launch projectiles with the aid of a hand-held mechanism. However, devices do exist to assist the javelin thrower in achieving greater distances, such as spear-throwers or the amentum.

Ancient Celtic warfare refers to the historical methods of warfare employed by various Celtic people and tribes from Classical antiquity through the Migration period.

The Neo-Assyrian Empire arose in the 10th century BC. Ashurnasirpal II is credited for utilizing sound strategy in his wars of conquest. While aiming to secure defensible frontiers, he would launch raids further inland against his opponents as a means of securing economic benefit, as he did when campaigning in the Levant. The result meant that the economic prosperity of the region would fuel the Assyrian war machine.

Major innovations in the history of weapons have included the adoption of different materials – from stone and wood to different metals, and modern synthetic materials such as plastics – and the developments of different weapon styles either to fit the terrain or to support or counteract different battlefield tactics and defensive equipment.

In ancient Egyptian society chariotry stood as an independent unit in the King’s military force. Chariots are thought to have been first used as a weapon in Egypt by the Hyksos in the 16th century BC. The Egyptians then developed their own chariot design.

The ancient Chinese chariot was used as an attack and pursuit vehicle on the open fields and plains of ancient China from around 1200 BCE. Chariots also allowed military commanders a mobile platform from which to control troops while providing archers and soldiers armed with dagger-axes increased mobility. They reached a peak of importance during the Spring and Autumn period, but were largely superseded by cavalry during the Han dynasty.

Ancient Greek weapons and armor were primarily geared towards combat between individuals. Their primary technique was called the phalanx, a formation consisting of massed shield wall, which required heavy frontal armor and medium-ranged weapons such as spears. Soldiers were required to provide their own panoply, which could prove expensive, however the lack of any official peace-keeping force meant that most Greek citizens carried weapons as a matter of course for self-defence. Because individuals provided their own equipment, there was considerable diversity in arms and armor among the Hellenistic troops.

The military nature of Mycenaean Greece in the Late Bronze Age is evident by the numerous weapons unearthed, warrior and combat representations in contemporary art, as well as by the preserved Greek Linear B records. The Mycenaeans invested in the development of military infrastructure with military production and logistics being supervised directly from the palatial centres.